When we left Congo I thought I would never return. But after an extended furlough we did go back. When I left the Press I asked our colleagues to proceed just as they must have done if I had dropped dead. I knew that the Mission greatly overestimated my capacity for work. It would be injurious to the cause of literature in future, if they depended on me and failed to make the proper alternative arrangements. So on my insistence they reluctantly agreed to release me from the work which had been my very life for seventeen years, and find some other work for me. I hoped this would be to itinerate in the villages just as much as my strength would permit.

This volume does not have room for stories of our furloughs, which in themselves would fill a book. But our last furlough was so unusual that I must say a few words about it. It was wartime. We were sent to Capetown, South Africa, with bookings to the Argentine. But our ship never came. After two months we had to cross South Africa, and sail from Durban round the Cape of Good Hope and across to Buenos Aires on an armed refrigerator ship. Then we flew five days by Pan-American Airways to Rio de Janeiro, Recife, Belem, and Trinidad to Miami. At Richmond our daughters met us after a separation of six years and eight months. The girls had not seen their brother from age nine until age sixteen. Leaving him and Dorothy (Mrs. Joe B. Hopper, headed for Korea) in America, we started with daughter Alice, returning as a nurse to Congo, and others. To get to Africa we had to sail by army transport to Egypt. We flew from Cairo to Lagos on the west coast, then to Brazzaville in French Congo. By motorboat we crossed Stanley Pool to Leopoldville, then up river to Port Francqui, and on to Luebo.

The Mission assigned us to Kasha, the southeastern station of our Mission, some three hundred odd miles from Luebo. Kasha was just a few hundred yards from the railroad line from Port Francqui to Elisabethville, but the railroad station was five miles away at Luputa.

In opening new stations our Mission usually chose open country in the area to be evangelized, then built a station. Native people would move in, as permitted, to vacant land. Thus the local situation presented fewer problems. Because of schools, Church, and medical help the people liked to live near the Mission. Such people, together with the employees necessary for carrying on our work, would need building sites and garden space. If we had located in an established village there would be much conflict of interest, and many quarrels for missionaries to settle.

Mr. McKee started Kasha station on vacant land, after securing permission of the local chief, and of the Belgian government. It was his intention to keep the local population down to the absolute minimum, leaving the missionary free for itineration. But when we arrived there we found Kasha village already had as many as 300 residents, many of these being pupils in the school.

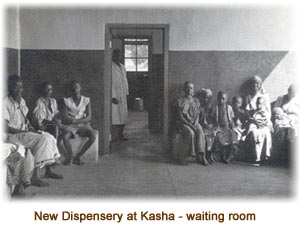

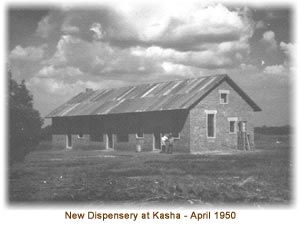

We lived at Kasha four years. Our duties were to preach the Gospel, and together with other missionaries supervise the outstation work, the school and the dispensary. When there were no other missionaries all the responsibilities fell on Mignon and me. At first Mr. and Mrs. Holmes Smith were with us a short time. Miss Margaret Moore also had the dispensary for a while. About half the time Mrs. Stixrud ( then a widow) was in charge of the flourishing dispensary. For some time Mr. and Mrs. Hoyt Miller were there to help us. But much of the time we were alone, just Mignon and I, with our African helpers. Some of these helpers were quite capable in their departments, having been trained on older stations.

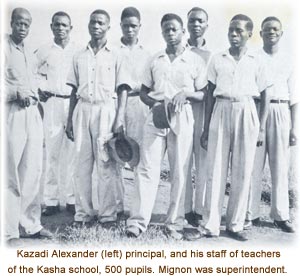

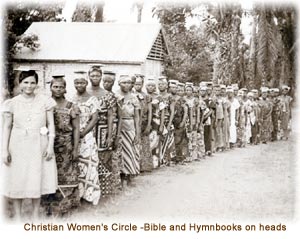

When we reached Kasha there were about 250 pupils in the station school, and it grew to 500 before we left. Without the able help of Kazadi Alexander, Mignon could not have handled it. In addition there were sixty-odd outstation schools, all calling for oversight, and, if possible, visitation.

During recent years the Congo government had been organizing its educational work throughout the colony. This was a burdensome undertaking. Education had been almost entirely in the hands of the missions, Roman Catholics and Protestant. In earlier years large subsidies were given to Roman Catholic schools, while the support for the Protestant schools principally came from Churches in other lands. More recently the government agreed to give subsidies to Protestant schools that qualified under the regulations. Our years at Kasha were in a period during which this process of organization was going on, and it made the school work far more difficult than it had been before. While most of the school work fell to Mignon, it also brought me many time-consuming duties, cutting down on time available for other work.

My responsibilities were many. First of course was preaching, and teaching the Sunday School teachers. Preaching was not only done on Sundays. Five mornings a week we had a sunrise prayer meeting. Part of the year it was a little before sunrise, part a little after sunrise. Much of the time the sun rose while we were in Church. Some of the time I gave a short Bible talk, the other part it was given by the elder Muamba.

There was also preaching on the outstations. However, when we were alone on the station my responsibilities tied me down so I could not itinerate very much. People in all our sixty villages wished for visits by the missionaries. When there is so much more than one can do he has to do what he can and commit the rest to the Lord.

The Christian people are taught to contribute to the support of native preachers (never to the support of the missionaries). The assembling of these offerings, and distribution of the money, together with such financial help as is available from America, requires much work. This fell to me, and much other paper work, so my office duties called for much time.

It was surprising how many French notes were needed in a year's time. With sixty families widely scattered, besides a local population of 300 persons, and hundreds of school pupils, many certificates of all kinds had to be written.

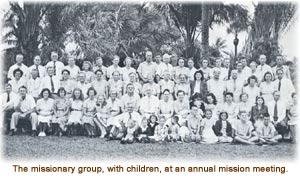

Once a year there was the Mission Meeting at which all Mission problems were discussed, and decisions made by vote of the majority. This takes time. But it also gives lonely missionaries fellowship both social and spiritual, so it is worth all the time it takes. The night meetings were usually given over to preaching and Bible teaching, which is needed by those who are so constantly giving out to others.

At the last Mission Meeting we attended I had an experience which might have ended badly. The meetings were held in a sun-dried brick chapel, with grass roof. There were no doors, no windows, just open spaces in the walls.

One afternoon Mignon said her usual seat in the corner beside me was too hot, and moved to the middle of the room. I kept my seat next to her corner. As I expected to take part in the discussion, I prepared my papers on a briefcase on the bench where she had been sitting. Some of them fell to the floor, behind the seat. I reached for them, and heard a strange sound, a sort of "whoosh." I could see nothing unusual. I had to reach down a second time, and again heard the sound, and felt drops of liquid on my bald head, and on my shoulder. I was puzzled, for the roof did not leak, and there had not been any rain. I kept looking around for some explanation as the business of the Mission went on. Finally I saw a snake down in the corner behind the seat Mignon usually occupied. I told the others, and with a stick and an umbrella some of them killed the snake. It was more than a yard in length. Dr. Rule identified it as the spitting cobra, a very deadly snake. It usually tries to blind its victim by blasting venom into his eyes. This produces temporary or permanent blindness. I presume he then bites the victim to kill him.

This was a close call for both Mignon and me. Had she had stayed in her seat that afternoon it is quite probable that she would have lost her life. We were so thankful she escaped.

Not having known anything about these cobras before, I hastened to look them up in an old encyclopedia when I got home. Shortly after that I killed a small one of the same species which stood up on the coil of its tail and distended its black hood just as the encyclopedia described it. It kept darting out its tongue very fast. It was just about thirty feet from our kitchen door at Kasha.

One other snake experience must be mentioned. I had fixed up a photographic darkroom at Kasha. One afternoon I was printing some pictures. I was in the darkroom with doors closed for an hour or two. Next morning I returned to get something. Observing some rubber cuttings lying in a corner, I decided to throw them out. Reaching for the second handful I suddenly saw that the remainder was not rubber, but two good-sized snakes coiled there. As it was dry season when the people burn off the grass on great areas of the plains, snakes seek refuge where they can find it. Almost certainly those snakes had been right there with me in the darkroom while I made the pictures.

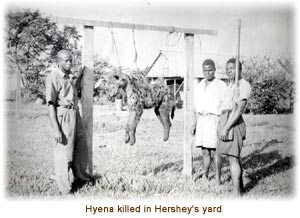

The sentry pointed out animal tracks in our yard. He and others wanted to set a trap, and I agreed. Next day they showed me that an animal had come and chewed off the rawhide strap they used to tie the trap, without getting caught. Again they set the trap and later reported that the trap was gone. They followed the trail, and out in the grass they killed the ugly hyena which had been caught and gone off with the trap. They were very proud of their catch.

Our system of Church government is Presbyterian. That means that all elders or bishops have equal authority and equal responsibility before God. That is the theory. But in the educational stage of developing the Church, the missionary by reason of longer training and greater experience must carry a disproportionate load. Our Kasha Presbytery met twice a year, during which meetings the work of all our evangelist teachers was reviewed, new workers were approved, unfaithful ones were disciplined, and in general decisions were made for the next six months. These meetings should have been a joy to me. For fellowship among Christians is an enjoyable experience, though the Christians are of different races. Sometimes I was privileged to have another missionary with me, but most of the time I was alone in the Presbytery with my African brethren.

But the joy of some of these meetings was marred by tensions which were hard to understand until in the course of time the secret sins of a few false brethren came to light. One man greatly tried us by keeping things on edge for about two years, before he finally admitted that he had married a second wife. He was removed from office, and his name stricken from the Church roll. The term in their language is to kill, or to extinguish, his name. But during the time he was with us he created many problems involving other people.

We had another brother who wasted Presbytery's time by talking so much without saying anything worth while. Without discipline he was finally persuaded to resign his office.

Among the group as a whole there was sometimes a sensitive spirit, readily offended, and sometimes there were sharp clashes of opinion. But generally speaking it seems that our African brethren cool off more quickly from such differences than would some of other races, and forgive and forget quickly. That does not include those whose hearts are unhappy by reason of hidden sin.

But problems of discipline were always with us. Members of the Church would fall into sin. Some repented and some did not. One of the encouragements of our missionary work lay in the fact that so many of the backsliders returned and asked to be reinstated in the communion of the Church. But I make no secret of the fact that many a Church member goes astray, causing sorrow to the missionaries and the faithful members of the Church. However, it is worth considering that in general Church discipline is much more faithfully practiced in Mission lands than in the homeland.

The native Church officers sometimes shift onto the missionary more than his proper share of responsibility for discipline, and for that reason he must carry a heavier load than the theory of our system calls for. During most of my years in Congo I was so occupied with other things that the load of discipline fell mostly to other missionaries and the native Church officers. But during our stay at Kasha I felt greatly burdened over matters of Church discipline, and that took away some of the happiness of my last term's work.

During our first year at Kasha I went through the most painful experience of my life. It concerned the discipline of an African elder (not a minister) whom we shall call Kampanda. He was overseer of our most distant section, looking after the work in nine faraway villages. An evangelist-teacher had been sent to work in his section, whom we shall call evangelist Kansanga.

This man came to me with a very strange story. He said that months before, when he went to that section, elder Kampanda, according to Kansanga's wife, had seduced her. They were guests at the elder's house. Kansanga left his wife there while he went to his new village to arrange for a house. On his return his wife told him about it.

Naturally I wondered why he had let this dreadful thing remain a secret for months. He explained that the elder bribed him not to tell, and at the same time threatened him with dire consequences if he did tell. So he kept silence, he said, until his conscience compelled him to come to me to reveal the truth.

The story as a whole had a number of details that seemed hard to understand, and difficult to believe. But the charge was so very serious that I felt obliged to call a meeting of Presbytery to judge the matter.

This meeting lasted four days, and was a time of heartache such as can be understood by those who carry in their hearts a real love for the Church of our Lord Jesus Christ. It was intensely dramatic, but no one could enjoy the drama.

I was the only missionary present. All sixteen pastors and elders came. One of them was elected moderator of the meeting. The evangelist Kansanga was present, and his wife, the accuser. The accused elder Kampanda was there, also his wife, who was a fine Christian woman, totally loyal to her husband. She refused to believe the charges against him. Both of the women were mothers of large families.

All the charges were brought before Presbytery, and none of the vile details were omitted. Elder Kampanda, in the presence of God, solemnly declared he was not guilty. There was endless questioning and wrangling.

The debate and questioning went on for four days; oh, what painful days they were. At the time we still had within the Presbytery a few men whose later history showed that they were living wrong, and therefore did not have the peace of God within their own hearts. Their nervousness and unreasonableness, added to that of the three parties immediately concerned, were what caused most of our trouble in solving the problem.

I tried to keep myself within the limits of the Presbyterian system, which means that I was sitting only as a member of the court, and not as a ruler over my African brethren. Besides that, I knew very well that the Africans were much better judges of the guilt or innocence of the accused than I was. So I sat and listened hour after hour, day after day, though it was almost too much for me to take.

Personally, I would not have been willing to be convicted on such evidence as was presented. For the woman who brought the accusation was admittedly an adulteress. I thought upon the case of Joseph and Potiphar's wife, who accused Joseph falsely. On the other hand, if the story were untrue, it was hard to see why the woman would incriminate herself by saying anything about it. No one else was accusing her.

In fact, she did try to throw the initial responsibility upon the elder Kampanda by a tale which I found it impossible to believe.

Before these charges against elder Kampanda came to my attention I had heard that he had previously been accused of other misdoings of various sorts, but always managed to wiggle out and get himself cleared. That had made me doubt him.

Another of the elders (he was later proved to be living wrong himself) at one point in the discussions became so furiously angry that he said to one who argued against his views, "If I were not a Christian, and in this place, I would kill you."

What we needed was to get a decision, guilty or not guilty, and to end a meeting that was doing nothing but increasing bitterness among them. But I was only one member of Presbytery, and I failed dismally in all my efforts to bring the matter to a vote.

After recess one morning Kansanga's wife walked into the meeting with a piece of rope over her shoulder. When the meeting was called to order she rushed across the room and threw herself prostrate at the feet of the elder Kampanda, with the rope over her shoulder. She said, "You know that in our tribe (they were of the same tribe) this is a matter of life and death. I dare you, according to the customs of our tribe, to step across my body and say you did not commit adultery with me."

We refused to permit heathen custom to be used as a means of settling a problem in the Church of Jesus Christ, so we obliged her to return to her seat. But the atmosphere was electric and I feared that physical violence might result before she was gotten back to her seat. Quiet was restored, and the meeting went on.

But as soon as the discussion started, she again rushed across the room, threw herself into the lap of the elder Kampanda with her arms around his neck, and said, "You promised me that if our affair ever became public you would marry me."

It was very hard to get her away from him. She was determined to stay there. At last she was quieted and persuaded to return to her seat.

Feeling that I myself would not be willing to be convicted on the little evidence as presented, though there might be truth in the charges, I made a motion stating that it was the judgment of the majority of the Presbytery that the charges had not been proved. When put to a vote this motion failed to pass. Since that meant that a majority believed the man was guilty, I finally succeeded in getting a vote on the opposite idea. It was the judgment of a majority of this Presbytery that elder Kampnda was guilty, and with great sorrow we were obliged to remove him from his office. The motion carried. That was followed by adjournment.

When the meeting closed I was physically and mentally and spiritually exhausted.

(About two years later ex-elder Kampanda admitted to me that he had repeatedly sinned with Kansanga's wife, but he said that part of her testimony had been false. He claimed that it was she who led him astray. Both Kansanga and his wife later led such lives as to indicate that both of them belonged to the followers of Judas rather than the followers of Christ. But oh, what damage had been done to the Lord's work in that section.)

The last day of Presbytery I had some temperature. When we adjourned I went home to bed with a bad malaria fever. I had not been so ill for many years. We were alone on the station, so Mignon treated me for malaria. I took both atabrine and quinine. By and by the fever was broken. But I was unable to sleep day or night.

Miss McDonald happened to come to Kasha and wished to go to Bibanga. As she was an excellent driver it was agreed she would drive us in our station car to Bibanga, where two of our Mission doctors had gone for other reasons. They took us on to Mutoto so Dr. Smith might have time to check me over, as it seemed possible I might have African sleeping sickness.

As I could not sleep without sedatives it seemed I might have to be sent to America on emergency furlough. But after some days my nervousness subsided, and it was agreed I could return to my work.

For the rest of our stay in Africa, another three years, I discontinued the use of both atabrine and quinine, fearing the effect on my nerves. I switched to one of the newer drugs, called aralen, which seemed to prevent malaria without side effects.

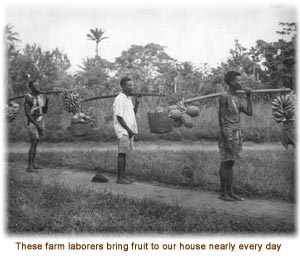

The supervision of the work in the villages presented numbers of problems. One of them was food for the families of the evangelist-teachers. Many times they came to see me and reported that their families were hungry. The chief complaint, when I asked why they did not cultivate fields, was that they did plant fields of corn and manioc; but elephants came and destroyed their fields, or monkeys came and stole their corn, or wild hogs came and uprooted their crops. In the whole four years at Kasha I never saw an elephant. But I saw trees they had broken, and footprints around a pool of water some miles away, and definite footpaths they had made through the high grass which elephants may have used for a long, long time.

As for the monkeys, it might be asked why the people did not kill them, for natives like monkey meat. By killing them they could increase their meat supply, and at the same time be preserving their other foodstuffs. But it is very difficult to kill monkeys with bow and arrow, and even with a shotgun it takes clever hunting to kill them. Gunpowder was costly, and could be bought only in limited quantities with a permit, and many of the available guns were not always good.

It was not really a temple. It was the porch of the chief's house, where he held court and made decisions about the affairs of his people. There he sat on a leopard skin when he held court. And close beside him was a small idol of carved stone which I suppose he trusted to help him. It looked like a very old idol, and was of better sculpture than other idols I had seen.

We went there on an Easter morning to preach the gospel of the Christ who rose from the dead. Parking the car outside we were led into the harem where lived the old chief with his many wives and children. Muamba, the elder who was with me, was a nephew of the chief. In fact Muamba's father had been the former chief of this tribe.

The old chief was also an old beggar. He began to tell me about the cough that has since taken his life. He wanted medicine, and I promised to send him some, which I did. He also begged for a dispensary for his village. He said the chief across the river had a dispensary. I told him our Mission dispensary was in his territory. But he wanted one in his own village, near his home. I suppose this was partly a matter of health, but also a question of prestige. Then he begged for shotgun shells. My escape from this was the fact that I had no gun, and did not keep shells.

Then we began to have Christian worship right there in what was for practical purposes the idol's temple. Nearby was the lifeless, powerless idol. It did not see us. It did not hear the joyous Easter hymns, nor the resurrection message reached by the chiefs nephew. Soon the service was over, and we came away.

The old chief has died since then. Where has he gone? God knows. I am glad that the eternal destiny of souls is in the hands of a God who is omniscient and merciful. If before he left this world old chief Kabue believed in the resurrected Christ, we will still meet him in heaven. But if a merciful and just God was compelled to send chief Kabue to that awful place prepared for the devil and his angels, I am thankful that we at least tried to bring to him and to his people the message of life eternal through Jesus Christ.

Tribal jealousies and hatreds between Africans have been problems for our missionaries through the years. Just as in the early Church there was conflict between Greek and Jew, so today there is bitter opposition between African groups, just because of tribal animosities.

At Kasha the animosity became evident between the Bena Kanyoka who were historically the owners of that section of territory and the people of outside tribes who came there to live. Once it flared up badly. Somebody placed an anonymous letter on the Church door. It started fussing and quarreling between the tribes in our Mission village. I was disposed to ignore the matter. But it grew worse, until the elders came to tell me that unless I did something about it, and promptly, blood would flow in the streets of Kasha village, and it would be my fault. So I called up three tribal groups separately, and talked to them. I tried to let them see that in the Church of our Lord Jesus Christ we were one new tribe, and must not hate each other. For the time being the feeling quieted down and nothing serious happened. But from time to time I could sense that the tribal animosity was still there, and might break forth at some future time.

When we took over Kasha station work from, Mr. and Mrs. Earl King he showed me the foundation trenches for building a new station Church, which was much needed. Money was available, but not a builder. Mr. King had been too busy to build it, and I also would be too busy with other things. The work had been started months before by Mr. Hoyt Miller. So we were very happy when Mr. and Mrs. Miller were temporarily located on our station. He was interested in building the Church. We were delighted, and he erected the building to our great satisfaction. I had some responsibilities in connection with this work, but he did nearly all of it.

When he got through with the Church he was looking around for other worlds to conquer, as he had his gang of builders organized. We had money for building a greatly needed dispensary, for the old mud and stick dispensary was far from good enough for treating the 90 patients a day who came there. Mrs. Stixrud and Kasongo had quite a reputation around those parts.

So Mr. Miller went ahead with the job, and was getting along fine, when his new work at Kakinda called him away; so the building work fell to me. I tried hard to complete the building before leaving for furlough, and nearly succeeded. It was in use soon after we left.

Earlier in the term some friends in the First Presbyterian Church in GreenviIle, Mississippi, gave me a used automobile chassis and sent it to Congo. On this I built a house trailer for use in itineration. We liked it very much and enjoyed itinerating in it.

When we left for furlough we were looking forward to having more missionaries on the station after our return, and we hoped to be able to use our trailer much more, in visiting our workers in the widely scattered villages.

Busy to the last minute, we turned over our duties to Mr. and Mrs. Stuart, who were sent to relieve us, and started for what we expected to be our last furlough. We hoped after one year to be back at Kasha for one long last term before our retirement at the end of forty years of service.

It would have been hard to say a final farewell to all our friends and to all our work, but as a year is not very long, we could say goodbye rather cheerfully. So we started for America.

The routine medical examination was made on arrival in Nashville. I thought I was in good shape and had passed the examination. So the report of the doctor surprised me very much. My condition was reported to be such that I must not return to Africa. With the proper medical care and necessary dieting, I might live and work for years in America. But our life in Congo had ended. It was a great disappointment.

We started our Christian service with the verses: Trust in the Lord with all thine heart, and lean not unto thine own understanding; in all thy ways acknowledge Him, and He shall direct thy path (Proverbs 3.5-6). We trust Him now to direct us in our retirement.