Before 1885 Congo was a vast country of numerous tribes with many languages and customs all different from each other. David Livingstone, great Protestant missionary and explorer, supposed to be lost in Central Africa, was found by Henry M. Stanley. This contact resulted in world interest in the Congo country. Stanley looked for some government to develop the strange land. He found nobody who cared except King Leopold II of Belgium, who wanted a colony. He and others in 1885 organized the Congo Free State which in reality became a tremendous private domain with Leopold as sovereign.

As the years passed and exports from the Free State grew, news reached the outside world that all was not well with the Congo. There was world-wide criticism of Leopold's regime. It was then decided that Belgium should take over jurisdiction in Congo, and what had been the Congo Free State became a colony of the Belgian nation. A Charte Coloniale was given the Congo by the government of Belgium in 1908. That Charter created the colony to be known for 52 years as the Belgian Congo.

Under stress of international pressures from without, and some Congolese leaders from within, Belgium in 1960 surprised the world by granting independence to its former colony. Most of the Congolese people, and many people in Belgium also, were surprised. No battle was fought to win independence. Belgium voluntarily gave freedom to the peoples of Congo to avoid a long and bloody struggle such as preceded independence in some other lands.

But the independence came suddenly to a people who were not prepared for it. Elections were quickly arranged for multitudes of people who had never voted in their lives. A hastily organized nation came into being. The takeover was peaceable, but in a few weeks the army mutinied, and intertribal wars began which horrified the world. The United Nations with an international military force intervened. Some of that force still remains in Congo as this is written.

It is more than three years since Congo Belge became the REPUBLIQUE DU CONGO. Its brief history has been troubled by the efforts of some provinces to secede from the Central Government. The secessions have been prevented by action of the United Nations. As a result the Republique du Congo is still in control of a sort over the whole great land.

The conflicts between the Province of Katanga on one side, and the United Nations and the Leopoldville government on the other, plus numbers of intertribal wars in many areas, did great damage. They resulted in the destruction of many of the physical benefits brought to Congo by the Belgians. Railroad property suffered tremendous losses. Important bridges were blown up. River ferries were put out of commission. Railroad service was disorganized or stopped entirely. Highways built at great expense were made impassable. Many villages were burned and hundreds, probably thousands, of people were massacred. Many of the foreigners left the country in terror.

The business sections and some of the residence sections of prosperous cities became virtual ghost towns. In some places there was wholesale looting of mercantile establishments and private residences. Thousands of automobiles abandoned by Europeans were appropriated by natives who drove them until gas ran out or the cars were wrecked. Robbery was common. Breakdown of communications and transport and finance left thousands of people hungry, and many starving. Foreign organizations, including the United Nations and Red Cross and some Church organizations, imported food for the hungry refugees by any means available.

The well-organized medical services of the government and missionary organizations nearly ceased to function. In some places this was due to the evacuation of the foreign staff and the expulsion of trained medical assistants who came from distant tribes.

The number of displaced persons multiplied into thousands and thousands as well-established and profitably employed people were forced to leave their homes and flee to their ancestral areas. Often they found no place to go as their old homes and sometimes the whole towns they originally came from had disappeared entirely.

From some of these fearful experiences the Congo cannot recover for many years, even under the most favorable circumstances. Villages built of temporary materials can in some places be constructed in weeks or months, if the seasons are favorable. But replacing bridges and ferries, boats, and permanent buildings costs money, and the destruction of so many other things has indeed "killed the goose that laid the golden eggs." What was in days or weeks or months destroyed may not be entirely replaced in the lifetime of anyone now living. Poverty is still the lot of most of the people, hunger is common, and the discouragement resulting from all the aforesaid events prevents all too many people from using the resources still remaining to improve their pitiful condition.

We were missionaries, sent to Congo by the American Presbyterian Congo Mission, which began its work back in 1891 in the days of the Congo Free State. It continued from 1908 until 1960 under the jurisdiction of the Belgian Congo. After a brief evacuation in July 1960 it has continued its work under the Republique du Congo. More of that will be considered later.

It is to be understood that our Mission never interfered in the politics of the Belgians or of the Congolese. Its work has been entirely a mission of mercy under the Great Commission left by Jesus Christ to His Church, to heal and to teach and preach the Gospel. In its educational, medical, and evangelistic work it has pursued its course, recognizing the "powers that be" as being ordained of God. We have conformed to the lawful authority of the government in power as best we could. We taught the people to pay their taxes, to respect and obey the government, both their own chiefs and the foreigners recognized as rulers over the chiefs.

There is a parallel to all this in the New Testament. Jesus Christ Himself, coming with a message from God to the Jewish people, found them a subject nation, under the control of the Romans as we found the Congolese under the control of Belgium. So we felt justified in keeping hands off political matters as He did in His day. We had no commission from our God nor from His Church to liberate the Congolese peoples from a colonial government. Our duty clearly was, "submit yourselves to every ordinance of man for the Lord's sake."

But for the limitations and prohibitions of our commission it might have been natural for Americans to have educated Congolese people for republican government such as we believed in. If we had done that, Congo might not have found itself short of men trained for government office when the time of need so surprisingly and so suddenly arose. But if we had disobeyed our own commission and engaged in such activities we would certainly and without delay have been expelled from the colony. Thus we would have lost our opportunity to preach the Gospel to the Congo people. In being loyal to the Belgian Colonial Government we were without a doubt doing our duty.

June 30, 1960, was set as the great day for the inauguration of independence. A formal ceremonial was arranged at Leopoldville where Baudouin officially handed over his authority as King of Belgian Congo to Patrice Lumumba, the new Prime Minister representing the people of the former colony.

Independence was a time of joyful celebration which the people welcomed, but which most of them did not understand. Multitudes throughout Congo shouted for independence without knowing what it meant.

But peace and joy were not for long. Before the new republic could settle down to enjoy independence the army mutinied, and nearly destroyed the new nation. Struggles for power began involving personal, and also tribal, grasping for the reins of authority over the nation's people and the nation's wealth.

Powerful leaders arose supported by financial and political power from outside of Congo. Both Lumumba and his enemies had support from mighty interests within and outside of the United Nations. Congo came all too close to falling into the total control of atheistic communist nations, which would have terminated missionary work within the country.

The United Nations, sharply divided between communist and free nations, intervened in Congo to end the tribal wars which threatened to destroy everything worth while in the land. For about three years soldiers of the United Nations, from many countries, have been stationed in Congo, and have even fought in Congo, to secure peace. It is not yet clear when or whether this military occupation will end.

Within a month after Independence Day, fighting within the Congo became so fierce that the American State Department, under whose passport protection Americans were present in Congo, ordered the evacuation of American missionaries. This seemed impossible. Roads were closed in many areas, and our missionaries were cut off from avenues of escape. United States transport planes could reach a few large airfields in Congo. But most of our people were trapped on their own stations. Prompt action by two missionaries with light airplanes succeeded in carrying all missionaries to points where they could embark in large American planes for Rhodesia, south of the Congo. There was great confusion within the Congo, and nobody could predict what would happen.

From the time of their arrival in Rhodesia the missionaries began to study the possibilities of return to the people and the work they loved. Seven men were back in Congo very soon, scouting by plane to find out when it would be wise to return. Soon other missionaries began to return -not all, but many of them.

The missionaries returned to a new Congo. They had lived previously in a Belgian Colony. They were now returning to the Republique du Congo, no longer a colony, but a liberated people. Instead of dealing with Belgian Colonial Territorial Agents, Administrators, District Commissioners, Provincial Governors, and a supreme Governor General, they found all of these replaced by Congolese officials.

In many places there was chaos because of intertribal wars and personal struggles for power. There have been wars and rumors of wars between provinces and the Central Government. There has been international intrigue. There have been massacres and wholesale migrations. Oftentimes communications have been cut off. Railroad tracks have been torn up or blocked. Radio communications have been forbidden. Private transmitters were confiscated. Automobile roads were made impassable. Travel across tribal boundaries practically came to a stop.

This is not intended to be a history of Congo after independence. Our interest in these matters is strictly missionary. We write of wars, political matters, and the economic situation, simply as background of the picture of missionary affairs. Mignon and I gave the best of our lives to the work of Christ in the Belgian Congo from 1917 to 1950 and now we look back. What has happened to the work of Missions since? Has the missionary work of all the years been destroyed by the coming of independence to Congo?

Even during the period of evacuation by the missionaries, some of the work continued. Worship services were kept up by Christians in many places. Schools continued in many sections. On some stations hospital assistants carried on as much healing work as limited supplies and personnel permitted. Church leaders carried on as best they could. Reports we have heard indicate that Mission property has received better treatment than might have been expected. We understand that in general churches and chapels have been respected even where villages have been devastated.

The sudden removal of scores of missionaries gave the Congolese people an opportunity to decide whether mission work was helpful or harmful to them. Here were mission stations. The heart had gone out to them. When the passions of the moment born of tribal conflict gave the people any time for reflection they could consider what missionaries had done, and had not done. They had not engaged in commerce. They had not held government offices. They had lived in modest comfort, but not in luxury. Why had they been there? They had ministered to the sick. They had taught many useful things besides reading, writing, and arithmetic. They had brought the people the whole Bible in the Tshiluba language. They had taught them beautiful hymns and Gospel songs. As a part of their Gospel of salvation they had taught people honesty and fair dealing with one another. They had been the friends of the people. Now they were gone.

If the work of Christian missions had been a failure, here was the opportunity of a lifetime for Congo's people to get rid of missionaries and missions. Everything would now be different. Government was now in their own hands. Congolese held all government offices from territorial agent to Prime Minister of Congo. Now by refusing re-entry to the evacuated missionaries the work of missions could have been ended. But it did not happen.

The latest figure available reports that more than seventy missionaries are now on the field. Others are on furlough. Work has been resumed on most of the stations.

The missionaries are back again because the people want them back. Without doubt the ministries of healing have a share in this. A great medical work had been done on our stations. As people in Judea and Galilee long ago flocked around Jesus to obtain His healing touch, so people still come to our hospitals to be healed. The medical work has suffered by the tribal strife which followed independence. A hospital organization is not built in a day. It is a team formed by long years of training people in various skills which fit together for doing all sorts of things from washing and dressing sores to the most serious surgical operations. These groups of workers came from various tribes, which have recently been in deadly conflict. Many of these workers had to leave their homes and mission stations and flee with their families to their own tribal areas. Some of them are lost to the medical work. It takes time to rebuild such organizations. Some local experienced workers have remained. New help is being trained. The work goes on. The people have learned in a new way to appreciate what Mission doctors and nurses mean to them.

Mission schools have a great share in this new evaluation. Education is appreciated more than ever. Many little schools in scores of villages kept going even while the missionaries were gone. Thousands of refugees found themselves in totally new circumstances and communities. Some of these were students, others were teachers. Before the smoke of tribal battles had blown away, efforts to establish schools were already in evidence. Some tribes had more refugee teachers than other tribes had, therefore were able to organize schools more quickly and effectively. All of them began to feel more than ever the need for missionary help in education. Missionaries were surprised and pleased to find how much of teaching would have continued even if the evacuation of foreigners had been permanent.

Admittedly things are much disorganized since the coming of independence. Under the Republique financial matters have not yet been stabilized. School teachers sometimes go for months without pay. Yet teaching continues as best it can. There is sound reason to hope that as things settle down under the new government school work will be better and better organized.

Our medical work has been a vehicle for the Gospel of Jesus. Our educational work has been another. Just suppose that these might have gone on by themselves, healing and teaching, but with the total elimination of Jesus Christ from the whole program, then what? Without the love of Jesus to give warmth and motivation, both healing and teaching would have lost their value. The very heart of all our missionary work has been the preaching and teaching of the Gospel of Jesus. Its inspiration came from Him. Our commission came from Him. The question is, has the planting of the Gospel seed during the whole period of the existence of the Belgian colony left any deposit of spiritual values? Are there any real Christians among the Congolese? If the missionaries had not returned, would Jesus Christ and His salvation have been forgotten?

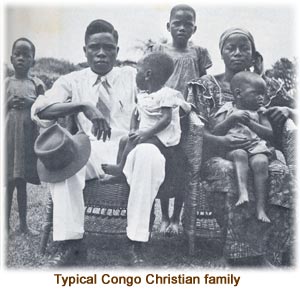

In fact there are many real Christians in Congo. There is a Christian fellowship that reaches across tribal boundaries and loves people of enemy tribes just because they are fellow Christians. During the days of tribal wars and forced evacuation and the loss of all earthly possessions this Christian love has been under a terrific strain. Sometimes it has seemed to disappear. But beneath all of the stresses there still remains a love for Christ and for His people.

Christians are only a fraction of the Congolese people. Outside of the Christian fellowship there remains bitter tribal hatred creating a poisoned atmosphere which to some extent affects even the Christians. Yet in spite of it all there still exists that Christian love for the brethren that reaches across the walls of separation and is at work to rebuild the Church of the Lord Jesus Christ. Outside forces have torn up our Church organization and our Mission work in various ways. It will take time to rebuild much that was torn down, but the healing of the Church continues.

The whole situation of our Mission in Congo is greatly changed. When the work was begun in 1891, and until 1908, our missionaries had to adjust to life under the Congo Free State. From 1908 until 1960 we had to adjust to life in a colony, among a subject people. This affected our operations in many ways. Now all that has changed. The Congo is governed by Congolese. They are no longer a subject people. In some respects there is a removal of restraints, which permits more freedom of action. No longer is there conformity to rulings of a colonial administration at Leopoldville which in turn was subject to Brussels. Now there are new adjustments to entirely different conditions. So many changes are taking place. Work of the past decades has raised up a generation of teachers capable of taking over the administration and teaching of primary schools. But the missionaries are still imperatively needed for high school and college and professional education. All these matters call for time and patience and love. The work of the missionaries during these days of reorganization is not easy. And the work of the Congolese Church leaders is not easy.

All of these arduous labors of reorganization and readjustment in Church and school, it must be remembered, are proceeding in a country where the government itself is being reorganized. It might have been supposed that the new government would continue with the same territories and districts and provinces which existed in the Colony. But all of the colonial organization was imposed by outsiders, and the dividing lines in many cases cut right across tribal boundaries. Thus the units were largely artificial. Since taking over power the new government has redivided the whole Congo into 21 Provinces instead of the former 6. When we remember that in the United States with one language it has taken decades for some states to redistrict themselves for representation in the state legislatures, according to their own constitutions, we can realize that the problem of redividing the Congo with scores of tribes and dozens of language groups to deal with, must be tremendous. We can see that all of the problems of Church organization are made yet more complex by the political complications which surround the religious and educational work of the Mission.

After independence the tribal war between the great Baluba and Lulua tribes reached Luebo. During the years since 1891 a town of 10,000 people had grown up around the Mission station. Most of the people belonged to various branches of those two tribes. The town was split wide open. There was fearful fighting. Whole sections of the town were burned. Horrible things happened. Neither of those tribes owned the land, which had belonged to the Bakete. The Baluba outnumbered and outfought the Luluas, and drove them across the Lulua River.

Luebo remained a depleted town, those remaining being Baluba or their friends. Many Baluba who had been scattered in the Lulua country fled to Luebo. The town was filled with refugees. Following the evacuation of missionaries from the Congo in 1960, the Luebo missionary group scattered. After their return to Congo the station sometimes had one missionary, sometimes none. Now, three years later, there are six.

For some time the Press was closed entirely. Sometimes a group of Congolese printers did some printing. But the Press was in a sad state. It seemed as if its history of many years of useful work had come to an end.

Before independence the women of our Church in America had designated a large share of their Annual Birthday Gift for the Mission Press, and for literature for the Congo Mission. Providentially the ladies went on with the project in spite of the disturbances in Congo. So even when the Press had reached its lowest ebb, the offerings in America were collected, and a large sum of money became available for an institution that was almost dead.

Mignon and I were delighted to hear that Lach and Winnie Vass, whose coming to Luebo saved the Press from going to pieces in 1942, had returned to Luebo twenty years later, to save the Press again. They have returned with the benefit of all their many talents, plus sixteen years experience in printing and publishing, boundless enthusiasm for the cause of literature, and the money needed for expansion.

The feeling of the Mission in regard to literature and the present situation is shown by this quotation from a letter of Mr. William Pruitt:

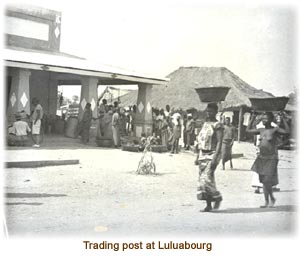

Our literature program, boosted by the Women's Birthday Offering of 1961, is booming. It is carried on in conjunction with neighboring missions who also use the Tshiluba language. A Scotch couple are now at the Bookstore and book warehouse in Luluabourg. A Mennonite is in charge of distribution, driving the big bookmobile throughout the countryside, restocking the various rural outlets operated by Congolese. Lach and Winnie Vass are at the Press, busy with production and editing. Even so we cannot fully meet the increasing demand for Christian literature.

A recent letter from Winnie Vass, and the Mission's recently published Annual Report for 1962, which she also wrote, give additional information from which we quote:

"You would have to be here at Luebo these days to know the fulness of joy and satisfaction in our work. All of the new Press equipment which the 1961 Birthday Gift of the Women of the Church purchased last year is operating except one piece. You should see the crowds of fascinated folk pressing around the doors and windows of the Press these days, their mouths agape with wonder as they watch the positively uncanny working of the various pieces of machinery. One window looks on the paper folder, where the pages pass through untouched, folded and folded and folded again, down to single page size. The automatic paper cutter just slices down through a foot of paper with ease. The Heidelburg Job Press sucks each paper up with little red suction cups, feeds it to the proper spot and presses the plate down and stacks the forms up on the other side -no hand touching them. After years and years (over sixty now) of all our equipment being handset, hand fed, and hand operated, this is quite an innovation and a thrill! Lach comes home to lunch at noon just elated with the work that is being turned out. The one piece of equipment which is still not functioning is our Monotype Compositor, which will set type automatically. We are still waiting on our order for Monotype metal. When it finally does come, then we will be setting the type by machine.

"The Protestant Bookstore of the Kasai, now known all over the Congo, has seen phenomenal growth. Total monthly sales until January, 1962, never passed $300.00. By November of that year, average monthly sales were well over the $3,000.00 mark. [One U.S. dollar = about 50 Congo francs.]

"The new edition of the hymnal, 20,000 of them, is almost completed, with a supplement of 100 new hymns."

One of the biggest thrills this past month was the completion of the first issue of our new Tshiluba periodical, called "Where Are We Going?" It is "Tuyaya Kunyi?" in Tshiluba, a catchy title. The first issue turned out beautifully, with colored cover and all and we are really proud of it.

The Congolese editor of Tuyaya Kunyi, this new monthly magazine, has proven his writing ability by authoring and publishing the first complete book by a Kasai Christian.

Our romance has not yet ended. Mignon and I are now in our mid-seventies, living in quiet retirement at Morristown, Tennessee. We have just celebrated our 48th wedding anniversary. The lovely lady from Missouri still makes a happy home for me in the evening of our life.

Last month we had a pleasant surprise. Our nephew, living in Washington, D.C., on August 11, 1963, wrote to his mother, who passed the word on to us:

The other day I brought a group of students to the President's Press Conference. In front of us several colored visitors were speaking French. I leaned over and asked them where they were from. One of them answered, "From Belgian Congo." I asked him if he was from near Luebo, and he answered that was his home town. I told him my uncle was a missionary in the Congo, and when I gave him his name he smiled and said, "He is a wonderful printer. He has printed many books for us. My father is a minister and knows Mr. Longenecker well." He gave his name to me: Kalongi. Uncle Hershey might like to know this

It is twenty years since we left the Mission Press at Luebo, thirteen years since we left Congo. We old missionaries are human enough to be thrilled by the assurance coming in this roundabout way that we are not yet forgotten in Congo.

One morning last week I waked with the conviction that in closing this book there should be mention of something very important. All the years in Congo we have lived in the hope of the Second Coming of our Lord Jesus. So we would remind our readers of what Jesus said (see Acts 1.8-11 RSV): "You shall receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you shall be my witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria and to the end of the earth. And when He had said this, as they were looking on, He was lifted up, and a cloud took Him out of their sight.

"Behold, two men stood by them in white robes, and said, 'Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking into heaven? This Jesus, who was taken from you into heaven, will come in the same way as you saw Him go into heaven.'"

Jesus is coming again! ! Are you willing to be His witness, right where you are, or anywhere on earth He may choose to send you?

In my boyhood, before I desired or planned to be a missionary, we sang words which may have helped to send us to Congo:

"It may not be on the mountain height, Or over the stormy sea,

It may not be at the battle front

My Lord will have need of me;

But if, by a still small voice He calls To paths that I do not know,

I'll answer, dear Lord, with my hand in Thine, I'll go where You want me to go."