It might seem that Hitler's sinking of an Egyptian steamer in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean had nothing to do with an American missionary couple in Central Africa, especially because at that time America was not at war. But the sinking of the Zam-Zam by a German raider changed the whole course of our lives.

We were tired, and needed the furlough which was due. Then too we wished to see those girls in America. Mr. Kirk Morrison, who had handled my work so well during our previous furlough, was selected to carry on when we went on furlough in 1941. But in the midst of our preparations we heard on the radio that the Egyptian steamer Zam-Zam had been sunk by the Germans. A number of our missionaries, including the Kirk Morrison family, were aboard that ship. We listened anxiously for further news, but it was slow coming. It was some weeks before we learned that the passengers on the Zam-Zam had been rescued by the attackers and carried to a port in France. Still later we learned that our people, instead of coming out to help us, as they wished to do, were being returned by Government order to the United States. Then, when we were all packed up for furlough, with bookings all made from Congo to Capetown to New York, and we were actually within four days of departure with other families of our Mission, we received a cablegram reporting that no missionaries were coming out for an indefinite period.

We were faced with the necessity for a sudden decision. We were free to go on a much-needed furlough. But we were sure that if we left it would mean real damage to the work of the Press. Some missionary who already had too much work would have to take over the Press as a sideline, the skilled men would become discontented and go to accept jobs where they could readily multiply their income, and from which I could not lure them back after furlough. I had put the best of my life into that Press organization. If it broke up I could not rebuild it in ten years. So it was my opinion that if we left it would set the Press back by ten years, which would be a great loss to the cause of Christian literature.

We asked the advice of the missionary group, but they were not willing to assume the responsibility of advising us either to go or to stay. The decision must be strictly our own. We prayed earnestly for guidance and carefully faced the alternatives. If we went on furlough, we were risking the future of the Press. If we stayed, we were risking our own health, for we were very tired. We loved that Press, and Mignon loyally stayed with me in the decision to remain with the Press and do what we could as long as we could, and leave our personal future in the hands of the Lord.

Then came Pearl Harbor, and America was in the war. By and by we might have gone on furlough, but it was impossible to secure ocean passage. The years added to that term did indeed leave their mark on our health, so after two additional years at the Press, it was necessary to give up the work we loved. After one more term in Congo doing other work, we had to be retired from the work in Africa by the Mission Board's physician. All that was a result of the sinking of an Egyptian steamer in mid-Atlantic. But in spite of the disappointing consequences to ourselves, we have always been glad we stayed at our work in 1941, for the Lord raised up capable help to take over, and the Press was saved.

It was decided that we must take a little vacation before we resumed our work. So we decided to visit our neighbors of the Congo Inland Mission, which had a number of stations beyond the Kasai River. We had often had their missionaries in our home, but had always been too busy to visit them. We borrowed a car and started off for a series of visits which we have always remembered with pleasure.

On one of those stations we met two unmarried ladies who lived together, and were very much devoted to each other. One day in conversation we were told that they were very much of one mind. They never had a difference of opinion but could be settled in one of three ways: either by the Bible, or the dictionary, or the Montgomery Ward catalogue.

Our itinerary took us through the diamond mining capital Of Tshikapa. We had known many of their people, but had never visited this place in all our years in Congo. We had friends there with whom we spent the night. It was a neat town with many modern conveniences. One thing that interested us was that at a number of places the streets of beautiful screened gravel were being dug up. We learned that this fine gravel had come years before from the diamond mines, after being picked over for diamonds. Now a new process recovered the diamonds more efficiently. So they were running the gravel through the new process. It was profitable, for they could count on a fair number of diamonds for every cubic yard of gravel handled. I had long looked forward to walking the streets of gold in a better world, but never dreamed of walking on diamond streets in this world.

We returned somewhat refreshed to our home at Luebo, to unpack our things and resume our work. We had lived in that brick, cement-floored, metal-roofed house four years, and had not been troubled by termites. But when we brought down our trunks from the garret we found that termites had gone upstairs through the mud mortar of the cement-pointed brick walls, and made inroads on the contents of our trunks. If the things had stayed there through a year's absence much damage would have been done.

We carried on our work until the November Mission Meeting, which was held that year at Luebo. Winifred, older daughter of Dr. Kellersberger, was now Mrs. Lachlan Vass.

One day she told me she believed her husband would like the work at the Mission Press. As he was in bed with a bad fever we could not ask him at once. As he recovered we learned that he would be glad to come, so the Mission appointed him to come to help with the Press.

Both Mr. and Mrs. Vass are highly talented people. He learned the work at the Press in a surprisingly short time. This greatly pleased me because I was too tired mentally and physically to give him the assistance he should have had. He did so well that in the spring of 1942, when it was impossible to get passage to America, it was decided to send us to Johannesburg, South Africa. Mignon needed some X-ray work which could not be had in Congo at that time.

The Vasses were second generation missionaries. Her father was Dr. Kellersberger, whose hospital I built during our second term. Mr. Vass father had served a number of years on the Mission long ago, was captain of the Mission steamer Lapsley, and when on the station he was in charge of the then little Mission Press. One of his employees there was the elder Mandungu, who helped me all my years at the Press, and was still there as a link between the Vasses, father and son, over the years, when Lachlan Junior took over from me.

We started on the long railroad journey via Elisabethville, Buluwayo, and Mafeking, to Johannesburg. We learned that we could stay at Brook House, Pretoria, a notable rest home for missionaries, and commute to Johannesburg when necessary.

X-rays showed that Mignon's ulcer was already beginning to heal. She was put on a diet. We were to spend three months in South Africa. We stayed two months very happily at Brook House, meeting missionaries from a number of African countries who were unable to take regular furloughs on account of the war.

Those were dark days for South Africa. During those few months Tobruk (on the Mediterranean) fell to the Germans, and it seemed as if the whole of Africa might fall into the hands of Hitler. Husbands, sons and brothers of our friends had been in Tobruk, and now it was not known whether they were dead or alive. The future of all missionary work in Africa was at stake.

Apart from the war, the only unpleasant thing about our stay in Pretoria was that we were robbed. One night the robber came right into the room where we both slept, and stole most of our possessions, to a value of about $250.00. As it was cold, it was specially inconvenient that he took all our winter clothes. He got my briefcase containing money, passport, and our return tickets for the long journey back to Congo. Christian friends in Pretoria helped us out, showing that the people of Christ are even now experiencing the answer to His prayer, "that they all may be one." Fortunately the thief did not want anything that could incriminate him, so all our papers, including passport and railroad tickets, were found in the garden. Detectives checked on the case, but the rest of our things were never found.

Our visits to Johannesburg were most enlightening. We had not realized that Africa held so modern a city. Pretoria too was more of a city than we had expected to see. But it is much more South African than is Johannesburg, which in some sections might almost have been transplanted from New York.

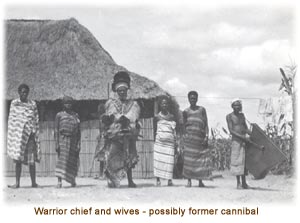

After a month spent at Port Edward, a country place south of Durban on the east coast, we were ready to return to Luebo. On arrival there I resumed work with Mr. Vass until Mission Meeting. At that time there was need of a matron for Central School. So Mignon volunteered to become matron there for six months. The Mission accepted her offer. The Mission appointed me, while making my home base with her at Lubondai, to itinerate as much as possible in the territory of our new station at Moma, among the reputedly cannibal Basilu Mpasu tribe.

The territory of the Basilu Mpasu had but recently been added to the responsibilities of our Mission. There were slightly trained teachers in something more than twenty villages, one station school, and one good sized regional school, in the area. I was to visit and encourage these workers, and to preach the Gospel. I traveled in a Ford station wagon, sleeping alone in the car at night. In the daytime I was always accompanied by my cook (our house servants were always men) and by an elder who was familiar with the territory and knew the workers.

The automobile roads were for the most part good, but narrow. The tall grass stood like solid walls on both sides. On these narrow roads one often met flocks of goats and sheep which obstructed travel. The car could not pass through the flocks, and the animals refused to leave the roads. As a result we lost much time following sheep and goats for as much as a half mile at a time. In view of the meat shortage among Kasai people generally, I felt like congratulating the Basilu Mpasu upon being able to eat all the meat they wanted. I was quite let down when I was told that public sentiment against killing these animals was so strong that a man was afraid to kill and eat his own goat. They said they were used for marriage dowries. But what use are they to the man who gets them? Why should anyone bother to keep sheep and goats if he cannot eat his own meat? Then they explained that the animals were kept for use at funerals. When a man died his livestock was killed and buried with him. It was so great a disgrace to be buried without any of these animals that men were known to trade off their own children into slavery to acquire sheep or goats for their own funerals.

A school teacher wanted me to take legal action to compel a father to return to the school his son, whom he had traded off to another village to get some livestock. It sounded as if that sort of thing were commonly done. But sometimes it is impossible to prove in a court of law what everybody knows to be true. It seemed quite certain that nothing could be accomplished by law against this horrible custom until a greater number of people were Christians and some public sentiment was raised against such practices.

Hearing how careful they were to preserve their animals for their funerals I was concerned lest I should accidentally kill a sheep or a goat of the flocks blocking the roads, and thus invite an owner to take vengeance on me. So I drove very carefully. One day I mentioned this to the elder. He laughed and said the owner of a goat would be grateful to me for killing it. In that way he could feast on his own meat and yet escape blame for killing it.

It was said that even a poor man ought to have three animals buried with him, and a well-to-do man no less than thirty. A chief might be accompanied to another world by as many as 300 goats and sheep. Such wasteful slaughter among a people so meat hungry seemed almost tragic. So I made more inquiries. It was admitted that nowadays the mourners did actually eat as much as half of the animals killed; formerly all of the meat was buried.

The Basilu Mpasu wore very little clothing, and seemed to be proud of it. The women wore less than the men. While often adorned with beautiful strings of colored beads, the women as a rule wore only the merest fragment of cloth hung from a string, or string of beads, tied around the waist.

The people love to dance away into the night. I was staying in one of the villages for a few days. The chief was complaining that the government was always calling on his village for soldiers, or for men to work the roads, sometimes to recruit labor for distant mines. He had so few people left, and they were tired. I asked him whether he had ever reflected on what the state officer might be thinking when he spent a night in the rest house I was occupying. I had listened away into the night to the sounds of drums and dancing. It seemed that any state officer, staying in the same place, would feel sure that there remained plenty of people, and that they were not tired. People who could dance like that until late at night must have plenty of strength left. He looked thoughtful, and said he had not thought of that.

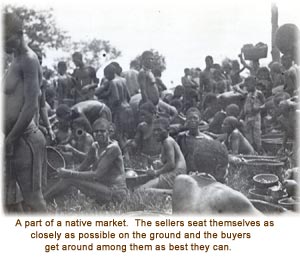

The big market at Turume is a very interesting place. Here the people come in crowds to buy and sell. Here we saw what I supposed was primitive crap shooting. Down on the ground the men squatted, and they were so fascinated by their game that even the unusual presence of a white man did not divert their attention.

In the same market I saw what looked like mesmerism or hypnotism. Two men sat on the ground facing each other. The one was looking the other right in the eyes, with fixed attention, while the other looked at him just as fixedly, and was going through a seemingly endless series of incantations. No doubt the second had been handsomely paid by the other to cure him of some malady or other, and he was not going to lose the power of his cure by looking around at anybody.

It was commonly reported that years ago human flesh was regularly sold in this Turume market. But the good old days were gone, and the white man's government now frowned on cannibalism, so such transactions must now be carried on in secret. But that they are still practiced secretly one cannot doubt if he travels long among these people. Day after day, night after night, we heard tales of cannibalism. Other tribes had heard so many of these stories that while men made long journeys alone in other parts of the Kasai, a stranger was dreadfully afraid to travel alone among those villages. One man who had traveled alone told that he had been attacked at dusk and knocked down and left for dead. His assailants had discussed his case, saying that it was so wonderful that today the creator had sent their meat so close to the village. They went off to get help to carry home their human game. But he crawled off into the forest, and recovered enough strength to get to a safe distance by morning. By keeping out of sight and avoiding the paths he finally escaped from their country.

The cannibalism was not mere talk. Some months later Mignon joined me at our station among these people, bringing our houseboy who did the laundry. The Carper family also had a few boys from other tribes. One day this group came to us excited and frightened. They told us that five miles down the road a strange woman from a distant tribe was visiting a relative. A passerby saw her lying alone in a field bleeding to death from a stab wound in her back. He ran to call help, but when they returned the corpse was gone, presumably carried off into the dark forest to be eaten.

One day I was talking to an intelligent chief of one of their villages. He had learned to read, and bought a Bible from me. He said, "Years ago we used to have wars with other villages. But the white men made us stop those wars. Now we hear that the white men themselves are having a much bigger war than we ever had. Do you think it might be all right for us to begin again having our wars just like we used to have?" Well might a missionary blush as he thinks upon the implications of that question.

Those primitive people, way back in the remote wilds of Africa, did suffer a great deal by reason of the white man's wars. Back in the most distant villages we would call for the group of catechumens, only to be told that most of the people had left their homes and the cultivation of their food crops, and gone off to camp for days and weeks in the forest, to get up their quotas of rubber demanded by the government to help the war effort.

Each able-bodied man was given a card on which was recorded whatever he had produced and sold to help with the war. The man who did not have a satisfactory report on his card was subject to penalties. This of course was happening while the people of Belgium were under Hitler's yoke, and people all over the world were suffering inconvenience and hardship. These people could not understand what it was all about.

It was said that in a certain village which I visited the chief had called up all the able-bodied men of his chefferie to present their production cards. This time a European recruiting officer appeared, lined up the men, and picked certain ones for military service. This was the draft carried to the uttermost part of the earth. One man was chosen and sent away to be a soldier. His brother was so violently angry he determined to kill the chief in revenge. Someone warned the chief, so he stayed hidden in his house and did not show himself. After the killer had lain in ambush a long time and failed to see his quarry, he killed the chief's mother in order to get rid of the anger in his heart.

These people had formerly been fierce fighters. Mr. Stegall wanted to get some pictures of their war dances and get a recording of their war cries as used when they went into battle. He told us about it soon after he made the recording, which was made without the knowledge of the warriors who put on the program for pictures. After the show was over the men were gathered in a large group near the tape recorder. Without announcement Mr. Stegall turned on the machine, suddenly breaking forth with the wild, loud, blood-curdling battle cries which these same men had demonstrated just a few minutes ago. In terror they ran for their lives. It was all very amusing when they learned that they had been frightened by their own wild yells, which sounded as if some enemy village had made a surprise attack.

The Basilu Mpasu are a comparatively small tribe and less closely integrated than some other tribes. The language and customs varied from village to village, so it would be almost impossible to produce a literature that would satisfy them all. In this and other small tribes there is a turning to the Tshiluba, a much superior language which is spoken by as many as two million people. Our school teaching is done largely in Tshiluba, in which we now have a considerable literature including the entire Bible. It was translated and has since been revised. It is published by the American Bible Society.

Mr. and Mrs. Vass were doing excellent work at the Press. They were due a furlough. They offered to go to South Africa for a six-month furlough if we would relieve them at the Press for that length of time. So we returned to Luebo to take over the work. They had already rented an apartment in South Africa, and the time of their departure was near. Then, just a few weeks before they were to go, I reached a state of nerves where I was continually on the verge of tears. It was clear that I was too much worn out to handle the job, so the Ad-Interim Committee decided that we must go on furlough, and leave shortly.

This was the price we had to pay for our decision to stay on in 1941. But we did not regret the decision, for the Press organization had been saved. When we packed up to leave I felt sure I would never see Africa again. In fact, I was so nervous that I did not want to see Africa again, ever. I had taken anti-malaria drugs so long I felt that I could endure no more of them. We started for America by way of Capetown. But it was wartime.