Returning from America by way of England and Belgium, we finally arrived at Luebo, and I had before me the most exciting period of my life.

Our fourth furlough in America had been a very busy time. We needed another press, a first-class typecasting machine, additional equipment for photo-engraving, and numbers of lesser items. All of this equipment must be carefully selected, and the money found, before any purchases could be made. At last all this was done, and now we were back, waiting for the shipments to arrive.

Money was still scarce, and I did not want to spend one cent more than was actually needed. It was just as important that we should not spend one cent less. A factory rebuilt press could be bought for much less than a new one. Therefore a rebuilt Pony Miehle Press was selected. Some people recommended automatic presses. Such presses are complicated and costly. Since our labor in those days was very cheap, and our editions not very large, I decided on a hand fed press. This proved to be quite satisfactory.

Careful study showed that nothing less than Monotype quality type would meet our needs. This machine was costly, but I believed the Lord would provide the money needed. To make sure this was the machine we needed I spent a week in the Monotype school in Philadelphia, learning to operate the typecaster, take it apart and reassemble it. Some may not know that the Monotype outfit employs two units. One is the typecasting machine proper, with many costly accessories, which casts the type, one letter at a time. The other has a keyboard like a typewriter which perforates long paper rolls something like those used on player pianos, only narrower. The keyboard operator copies the manuscript in the form of holes punched in the roll of paper. This roll is transferred to the typecasting machine, and controls its operation. It turns out type already set, and needs no typesetters. My week in the school convinced me that for the time being we needed only the typecaster, not the composing equipment. I had been taught that it is not wise to put all your eggs in one basket. If we had depended on one operator, and he became ill, the Press would be tied up. The situation would be even worse if the machine broke down, for at that time there was no other Monotype machine in the whole of the Belgian Congo. So I insisted that what we needed was the typecasting machine. To save money, for these things cost thousands of dollars, I wanted to get a factory rebuilt typecaster. But I wanted a full equipment of brand new matrices to make exactly the type that primitive people needed for learning to read.

Our next problem had been to find the money. We were in the mid-thirties, and money was hard to find. Our principal donors were Mr. and Mrs. George W. St. Clair, of Tazewell, Virginia, and their children. Other donors helped, but they were far the largest contributors. Some years later Mr. St. Clair told me that he had worked in his father's printing office as a boy. It was not easy to convince him about the Monotype machine. I learned that someone who did not understand our Congo conditions tried to persuade him that we needed a Linotype machine rather than a Monotype. My observations at the Monotype school convinced him, and the family helped us with thousands of dollars.

When the time came to order our machine I wished to place the order in Philadelphia. They said they could not sell to Africa, only to North and South America. I must buy in London. Because the British-made machine was different in some details, it was necessary for us to return by way of London. There I selected the typefaces, learned to operate the British machine, and bought it. I spent a week in the London School. Much more time was desirable, but I was needed at Luebo. I was most grateful for a set of instruction books on the operation of the typecaster, which helped me out of many a tight place.

A steam boiler, engine and generator had been bought in America. Installing all of these while editing the Lumu Lua Bena Kasai, doing much proofreading, and managing the Press in general, was enough to challenge any man's mettle. The equipment did not all arrive at the same time, so the installation took a number of months. The boiler was a return tube cylinder, and we had to build the firebox to hold the grates, and the whole enclosing structure, of brick. This we could do from the blueprints furnished by the boiler maker, but it was a new experience. Working with native helpers, and without the equipment so readily available for such jobs in America, it called for some homemade engineering to set up the outfit. When the boiler was in place and all built in, it was a question how we should erect the 30-foot smokestack on top of it. We laid it flat at the level of its base, anchored it sideways so the lower end of the stack could not escape, tied a steel cable at the bottom, and led it inside of the stack to the top. (The idea here was to be able to release this cable when the job was finished without climbing to the top of the stack.) The cable coming out of the top was then carried over a vertical ladder some distance away, so as to give an upward pull. Permanent guy wires were then fastened from points on the side of the stack, to points at right angles to the stack and in line with the base. When the men, all on the ground, pulled on the long cable over the top of the ladder, the top of the stack would rise high enough to permit straight pulling to bring the stack to its vertical position. A third guy wire at the rear would protect the stack from going beyond the vertical point and falling. Working with men untrained in such work was always a strain for me, for if there is a wrong way to do a thing somebody in a group is almost sure to find it. Under such circumstances the best planned operation is potentially dangerous. Therefore I thanked God that everything went according to plan. The stack stood there for many years, until it finally rusted through. It gave a wonderful draught, and the boiler worked just fine.

Next we had to install the steam engine, my first job of that kind. We had enough tools for the job, and soon it was ready for work.

Next came the electric generator. I had never installed one. It seemed that if every Tom, Dick and Harry could make a generator work on an automobile, the basic principles being the same, I ought to be able to make one work in a stationary position. Also I derived a certain comfort and confidence from the fact that Mr. Shive and Dr. Stixrud on our station would make excellent consultants if needed. Both were very busy and I would not call them unless it became necessary. Yet I knew that if I got into a jam they could help me out. Finally the generator was in operation, but I came near losing an eye while fixing up a switchboard. Somehow I shortcircuited the current on the switchboard, melting some copper which flew straight towards my eye. It struck one lens of my spectacles, melting a bit of the glass, and that saved my eye. Again I had cause to thank God.

The electric current was now available, so we could proceed to install the Monotype machine. The plan was to set it up in our little typecasting shop. It was too large for the door, so we had to break a hole through the wall, move the machine in, and rebuild the wall.

We assembled the machine, and thought we were ready to cast type. I put metal into the melting pot, turned on the current, and melted it. At that point I had to stop, and turned off the current. Before the generator was set up I occasionally had visitors, to whom I proudly showed our new Monotype. This included cranking the melting pot in and out of position. Then another visitor came, and forgetting the cold and solid metal now in the melting pot I began to crank the pot out of position. BANG!! went the machine. I had broken our precious Monotype before we cast a single character. London and a new part were about 6000 miles away. Self disgust was mingled with bitterest disappointment.

Checking the damage, I found I had broken one of the levers supporting the pump in the melting pot. I supposed it would cost me $10.00 postage to get the part by air mail. It must be ordered at once. It arrived in a month, and the postage was $19.50, enough to take away my breath.

Long before the new part came my patience had worn out, and I did a job of blacksmithing and machine work with a piece of angle iron, a hacksaw, a drill press, a forge and an anvil. I was neither a blacksmith nor a machinist, but in my desperation I made a piece that did the work. I was casting type a few weeks before the new piece arrived. Some years later I explained to the Monotype agent in Capetown what I had done. He found it hard to believe that I accomplished it, for it was a difficult piece to fit, and worked within narrow limits. I have heard it said that the Lord helps fools and little children. Certainly He has helped me in many a hard place. He knew I was doing it for Him.

Now We Were Happy!!! We were all set, and ready to go! Only those who know and love a perfect instrument can appreciate the joy I got out of the work of that Monotype machine. We had suffered so much from unsatisfactory type for so many years, and now at last we were getting exactly what we wanted. I felt like singing the Doxology all day long! I was used to working overtime just because my work was so fascinating. Now I worked over-overtime. The men loved the new type, and we had a wonderful time. The electric current provided for the Monotype machine also supplied the needs of the little photo-engraving laboratory: the arc lamps, the enlarger, etc.

Assembling the Pony Miehle Press was also quite a job. It was a heavy machine and came in heavy cases. Un- loading these from the river steamer without the help of the lifting machinery ordinarily used on ships was quite difficult. The steamer landed on the far side of the river, and I went across with a lot of men from the Press to unload the cases. Down there in the hot sun we slaved and sweated. By and by it was noon, and the sun straight overhead. Mignon thoughtfully sent me a nice lunch. But my men had no food, and I wanted to do something about it. It was market day, so I sent a man to the market to see what he could find. He returned with a woman who had a basket of peanuts for sale. I asked the price. She said half a franc a cup. I said I would take them all. I measured them out, carefully counting the cupfuls, then counted out the money. She refused it. She named a considerably higher price for the lot as a whole. Instead of a reduced price for wholesale quantities, the ordinary commercial system was exactly reversed.

We at last got the new press up to its new home, and with a great deal of hard labor had at last assembled it. It was a used press. So a new hose-like cover was sent for one of the iron rollers. The hose had apparently shrunk, and the simple operation of placing that piece of hose on a roller became an impossible task. We tried and tried to force the hose over the roller, but it simply refused to go.

Elsewhere I have mentioned what a writer has called the "total depravity of inanimate objects." This case topped them all. By and by we quit trying, and proceeded with other work, all the while trying to think of some way to do this pestiferous little job. One day I had a new idea. Getting a bit of talcum powder I poured some into the hose, and rubbed some on the roller. Then with I very little effort the roller slipped into the hose, and the press was ready for work.

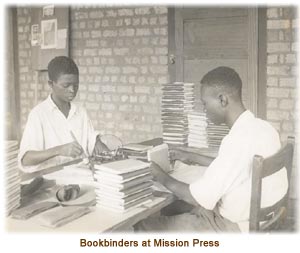

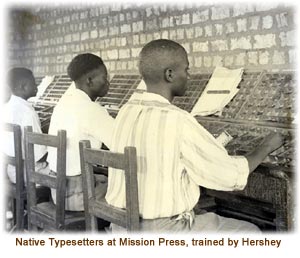

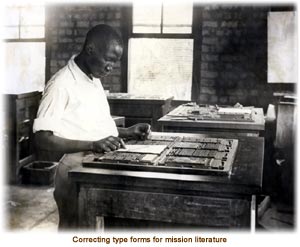

People visiting Luebo station usually found the Press an interesting place to see. Once a new Administrator had arrived at Luebo, and came across river to make his courtesy call. He was brought to see the Press. He was altogether astonished by what he saw. At that time we still had our artist. After being shown the typecasting, typesetting, presswork, bookbinding, drawing and photo-engraving all being done by Africans, he was amazed. He said, "Why, I have been working with Negroes it Congo for nine years, and I never dreamed that they would be capable of doing work like this." He returned next day with a colleague, to show him what wonderful things Africans were doing. We were delighted to see his very evident appreciation of what was being done.

For years I had done all the proofreading myself. Mr. Washburn suggested that I should have African proof readers to carry most of the load. I followed his suggestion. I tried to get manuscripts in such shape that I could hold the printer responsible to reproduce them as they were written. Printers in general would agree that is hard to do. But we worked on that basis. We had two proofreaders working as a team. One was to read the manuscript letter by letter, indicating punctuation and spaces. The other was to check the proof as the first man read. That is an awfully monotonous job, but it was the price of getting good printing, and we followed the system as long as I was at the Press. It was particularly useful when the men were printing in languages they did not know. We did some printing in English and in French. The bulk of our work was in Tshiluba. We also printed in Bushongo, and a little in Kipende and some other language. Printing and proofreading letter by letter made it possible to reproduce these correctly. The proofreaders were paid a straight salary so they would not be tempted to rush things through to increase their own earnings. Sometimes the printers fussed at the proofreaders for slowing down production. When the job was supposed to be ready for the pressmen, I always had the final word. I actually read many pages of the proof myself, to check any tendency to carelessness on the part of proofreaders or printers. The hardest job we ever had was the printing of a Grammar and Dictionary of the Bushonga language, by Mrs. Edmiston. I knew the English, but not the Bushonga. But the printers and proofreaders knew neither. As it was a book of 500 pages we sweated weeks and months over that exacting job.

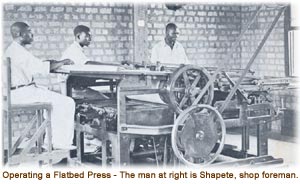

I made up practically all dummies for everything we printed. That is, after the typesetters had set up the type in their composing sticks, and transferred it to the type galleys trays) they would print what we called a galley proof of it. All the proofs of all the type for a certain job were turned over to me, and I clipped and pasted them as they were to be located on the pages. Then the shop foreman took over and had the type forms locked up in chases. Finally they made proofs for the proofreaders.

Our shop foreman, Stephen Shapete, has already been mentioned. He was a consecrated Christian. He and his wife came from Christian homes. He was a capable printer, able to do all the operations around the Press, which I myself was not able to do. He made a good shop foreman, and besides he was my friend. Without his help it would have been hard for me to organize the work of our Press. I had known him and a number of other boys who became useful in the Lord's work, for a long time. One of them was Kabamba, who became Dr. Stixrud's efficient helper at Luebo Hospital.

Shapete and Kabamba were next-door neighbors in the village. Both were deacons in the Church. Kabamba was found to have a serious case of diabetes. While Kabamba was being treated for that, Shapete became ill with influenza. He recovered slowly, and when he returned to the Press he was able to do little work, spending most of his time sitting near the boiler. By and by I was told that Kabamba was dying. The day before his death he sent me word that our mutual friend Shapete was suffering from tuberculosis, and I ought to have him examined. Shapete and others had the strange notion that to have tuberculosis was some sort of disgrace.

Kabamba on his death bed thought it necessary to warn me about Shapete's condition.

I sent Shapete to the doctor for examination. The report came back that he had a serious case of tuberculosis; he must stop work at once and be put on a special diet. We went as far as we could possibly afford to feed him and support his large family. But after a time he began to weaken, then died. Later his wife and three of his eight children died of the same disease. It seemed that the hope of curing this disease among our Africans was small. They are easy prey to all pulmonary infections. The new drugs for pneumonia are proving a great blessing and saving many lives.

Hitler invaded Belgium in 1940. That invasion affected the Congo in many ways. There was of course the danger that Hitler might take over all of Africa, including Congo. At the time of the fall of Paris it seemed as if the Congo might fall in a matter of days. De Gaulle's resistance in the French colonies made all the difference for the Belgian Congo.

There were many wartime inconveniences, including censorship. That was one of the most wearing experiences of all the years. We were required to submit all published matter to the censor, but specially the Lumu Lua Bena Kasai. Instead of sending the original manuscripts to the censor, it seemed it would be easier for him and for us to compose the edition, and send proofs of the final form to the censor. Very little of our material was ever rejected by the censor, as I edited it very carefully. The difficulty lay in the slowness of the censoring process. We had limited supplies of chases and press furniture, so the delays were a real hardship for us, and quite a strain on the nerves. I sent the copy to the Administrator, he sent it to Lusambo, which probably took a week. Then it would require a week for the trip back. Sometimes the copy was held a number of weeks at Lusambo. It was a monthly paper. Often the succeeding copy was ready for the censor before the earlier one came back for printing. This meant that two sets of chases were tied up with the LLBK instead of one set, and this slowed down our other work. All this was a great trial to me, but nothing could be done about it. The government officers were overworked, and I suppose the censorship vexed them as much as it worried me.

The Congo government was doing all it could to help the war effort. While Belgium itself was in the hands of the Germans, the Cabinet in Exile was functioning in England, and the Governor General in Congo was doing everything possible to mobilize all available resources to aid in an Allied victory. It is well known that the Congo supplies of copper, industrial diamonds, palm oil, rubber and uranium were important contributions to the ultimate victory. In addition to preparing for a possible invasion that never came, Congo even sent expeditionary forces of native troops and Europeans to help in active theaters of war in northeastern Africa.

I received a letter from Dr. Coxill, Secretary of the Congo Protestant Council at Leopoldville, saying that the Commander in Chief of the Congo Army had heard that I had a camera for making pictures for use in newspapers. This was to announce that the Commandant at Luebo would call on me in regard to making some pictures of native troops for use in newspapers in Congo. The Commandant came to call on me, and an interesting friendship began. I explained that as it was wartime my supplies were very low. But I was glad to do what I could to help the war effort, and would out of my little stock make ten copperplate halftones for the use of the government. If he would bring me the photographs I would make the halftones and return the original photographs. But he understood nothing of the complicated process. He supposed I had a camera which produced the pictures ready for the printing press. I explained that we must have photographs before I could start making halftones. He said it would be necessary to make the photographs. I told him I was extremely busy, and it would be hard to spare the time for a trip across river to take the pictures. He gladly offered to bring the soldiers to me to take their pictures. This was a thrilling experience for the Press employees. The Commandant and another officer drove up in a car, and a group of soldiers came marching up the hill. These were posed in various formations, and I took the pictures. All of this was fascinating to a crowd of visitors who came to see the show. A tense moment came when a soldier was posed with his rifle aimed just beside my right ear. To my native friends it looked as if I were to be shot, and for a few minutes they were somewhat concerned for my safety. The photographs turned out well, and I made ten excellent copperplate halftone pictures ready for the newspapers, which were sent to the military headquarters and were duly appreciated.

It should always be understood that while much of this story relates to earthly things, the entire motivation of my life was the desire to bring the knowledge of Jesus Christ, and Him crucified, to these African people. No matter what else I did, if I failed in that my life would be a complete failure. I am in total disagreement with those who say, as one writer did, that the missionaries should first heal and educate, and let soulsaving come later. These Africans were no worse off in heathenism than they would be with a Christless education. So the primary objective of all my work was to print the things which would spread the knowledge of Christ among the people. I loved to preach, and did preach whenever I could. But I profoundly believed that I could reach more people through the printed page and its readers, than I could by preaching only with my own lips. This burning conviction carried me through many a hard day, when, though weary of proofreading with sheets of paper sticking to my perspiring arms, I tried to get the Lumu Lua Bena Kasai and Sunday School lessons through the presses at the proper time.

One of the problems of printing in the tropics relates to the condition of the ink rollers. Many improvements have been made in the intervening years, but in those years printers had real trouble. There are in Congo many types of microorganisms which feed on many things. But their preferred luxury is printing press rollers. They roughen the roller surface, so it is difficult or impossible to get perfect ink distribution. There is also the question of hardness and softness of rollers. They do the best work when they have what is known as a tacky surface, which sticks a little to the ink and to the type. If the roller is too dry or too hard, the printing will not be good. Heat and humidity, on the other hand, tend to melt and destroy the roller and gum up the typeforms with a gluey liquid. A roller might seem just right in the morning, but by reason of heat or humidity be altogether unsatisfactory by noon.

We had roller moulds for casting our own rollers, and this had to be done whenever rollers were not working properly. Casting rollers and keeping them in condition is an art in itself. In America it is done by specialists. In Congo you do it yourself.

Our Monotype operator had become quite proficient in actually running the machine. That saved me much time, but I did most of the fine adjustments myself. I was in and out of the typecasting shop every little while when the machine was operating. One day I was working on the machine when they told me, "There is a snake in the type room." That meant he was just a few feet behind me. I turned and saw the snake as he ran down a hole in the wall by the doorframe. I hate snakes. It gave me the creeps to think of working with the constant threat of having the snake come out behind me. We decided the best thing to do was to blow flame down into his hole with a blowtorch. We did this. The snake came rushing out, and we killed it. Then we began work again. Somebody said, "There is another snake." It ran furiously out of the hot hole, and tried to run straight up the wall in an effort to escape. We killed that one too, then sealed up the hole with cement.

The editing of the LLBK was a never-ending job. It was not a large paper, just from 16 to 32 pages per month. Mignon wrote some material for women and children. I wrote some for other readers. We tried to get contributions from other missionaries, but never got enough. But there was a constant flow of material from African contributors, and this varied greatly in quality. The hardest part of my work was editing this native material. Nearly everything in the paper was in Tshiluba, with a little French now and then. Wading through three times as much material as we could print, sifting the wheat from the chaff, was really hard labor. Sometimes I grew very weary of it.

After some years of reading handwritten manuscripts, sometimes done in an almost illegible scribble, I arranged for our shipping clerk Mukendi to copy all handwritten manuscripts on the typewriter, double spaced, before I read them. Then I could edit much more rapidly, tearing up what could not be used, blue pencil here and there, interline a few words where needed, and sometimes have Mukendi recopy edited articles for the assistance of the typesetters and proofreaders.

My reward for all this labor came here and there in letters showing that the paper was helping lonely Christian workers to carry on their labors for their Lord. One of the most encouraging letters came from an evangelist of another Mission, hundreds of miles away, a man of a different language. He had learned Tshiluba so he could read our literature. He told how he had been working for years in a very difficult village. The people were hardhearted, there seemed to be no results of his preaching and teaching work. He was on the verge of quitting his work in discouragement, to take a much better paid job as a sales clerk for a white trader. However, he remembered the things he had read in the Lumu Lua Bena Kasai, so he decided to continue his work. Now he reported that everything had changed in that village. They now had a group of Christians there, he was happy in his work, and gave credit to the Luma Lua Bena Kasai for the fact that he was still working for the Lord.

Once I met a man who had been in prison far from home for manslaughter. He had found his wife in the arms of another man, and in sudden anger had killed him. For this he was sent to prison. He had now completed his sentence of six years. He came to see me, and reported that the LLBK had been his encouragement all those years in prison. He and other prisoners, having no other religious instruction, found food for their souls in our little paper which somehow got to him.

Perhaps it was David Livingstone who said he stood where he could see the smoke of a thousand villages where the name of Christ was not known. Part of my satisfaction as I toiled at my desk whether I felt like it or not, was in thinking that the Lumu Lua Bena Kasai was being read in a thousand villages where it was witnessing for Christ.

Once I was told of two incidents which had occurred years before. As they were similar, I relate only one. A Portuguese trader came to a Mission station to inquire about a paper called the Lumu Lua Bena Kasai. He said he had an employee who was quite different from the other natives he employed. He had wondered why. He found that this man was a reader of the LLBK.

It seems reasonable to hope that by and by in a better country I may have the joy of meeting hundreds and thousands of Africans who have been helped in their journey to the Celestial City by reading the little monthly Tshiluba language paper which represented the cream of the work of my lifetime.

During this term our daughters Alice and Dorothy were at Queens College at Charlotte, North Carolina. Counting on a four-year term, we expected to see them about the time they finished college. But war conditions stretched our absence to six years and eight months, so Alice finished her nurse's training at Johns Hopkins, and Dorothy finished her course at the Assembly's Training School at Richmond before we saw them again. Once Dorothy wrote that it was hard for the family to be so widely separated, but there were compensations. For instance, though thousands of miles apart from each other, our family was really closer together than some families living under the same roof in America. Mignon maintained correspondence from our end, and the girls were very good about writing to us.