Returning to Congo this time I knew where I was to go and what I was to do. I was very happy to return to my work. Things at the Press were in fine shape. Mr. McMurray had done excellent work in editing the Lumu Lua Bena Kasai, and in the general printing for the Mission. The printers were there, ready for work. We faced a great opportunity.

These were the years of the world-wide financial depression. They were very difficult years in the work of the Mission as a whole. Appropriations from America were reduced time after time, while the economic situation of the Congo became extremely bad. During the rushing twenties traders had opened up many small trading posts throughout the country. Though some of the traders were not a good moral influence, they were a financial help to our people who could sell them native produce and buy from them cloth and other needed articles. As world markets declined, most of these small traders had to fold up and leave the country. Numbers of these small places stood empty, with grass growing high where there had been busy trade before.

People who had gone away to work in the mines and other places came back to the country to live. The labor shortage eased up. Men who previously would have spurned our small Mission salaries would now have been glad to work for us.

But our appropriations for the support of hospitals, schools and evangelistic work were just a fraction of what they had been before. The annual Mission Meeting decided how the appropriations were to be distributed to the stations. Then the station meeting, held at least once a month, had to decide how to divide its share of funds. As missionaries were so busy during the day these business meetings were often held at night. For years money was so scarce that the division of funds between departments was most painful. Shall teachers salaries be cut again, or the preachers, or the workers at the hospital? Ought we to close down part of the great school, or cut down on the orders for medicines so urgently needed? Such practical problems had to be faced. Many times I returned home after station meeting and lay awake half the night worrying over the financial problems of the Lord's work. Our own salaries as missionaries were separate from the working budget. They were supposed to provide a living something like that of school teachers in America, just a modest living. But these salaries were reduced time and again. Yet out of their reduced incomes, inadequate for their own needs, many missionaries took money time after time to keep going the work they loved.

There was also the problem of missionary personnel. Our Board was unable to send out the new missionaries who wished to come, and were so very much needed. After some years of this, when some new missionaries began to arrive, someone compared the mission to a college without a sophomore class.

To save money on travel expense each missionary was asked to defer his furlough for one year, thus giving us a five-year term instead of four, though our doctors were agreed that four years in the tropics was enough.

Throughout this term we worried with financial problems. I wrestled with the question of proper salaries for evangelists. These men were unordained preachers and teachers, maintaining our schools in hundreds of villages. The Mission wished for the native Church to contribute enough money to support all their preachers. Money was scarce, and while substantial sums were contributed by the Christians, yet the total was never sufficient. Various schemes were proposed to the Mission, and some of these were adopted. Sadly for our work the shifting sand of international exchange with jumping of prices came in to break up the best of plans.

It will be seen that the financial jugglings of New York and London and Brussels affected poor people right into the heart of Africa. Financial worries spoiled some of the fun of what was otherwise a happy term for us. Even though salaries were cut repeatedly, the missionaries in general worried much less about their own needs than about the needs of the work.

During our third term I had gotten a start in photo-engraving with the crudest sort of equipment. With limited time and too little knowledge, meeting all kinds of obstacles including what someone has called "the total depravity of inanimate objects," I had produced some usable pictures for printing. I felt that I needed a better camera than the one I had made out of corrugated roofing. During the furlough I was looking for a photo-engraving camera that would really fill our needs. In Chicago I found what was called a darkroom camera. Instead of an overgrown camera with a large leather bellows, which invited destruction by tropical insects, a whole room was made into a camera, and the operator worked inside it. There had to be a small vestibule with double doors for a light trap, and tracks for moving the plate holder and focusing screen. The lens was mounted in a lens board fitted into the wall. The photograph or other copy to be reproduced was mounted on a copy board outside the camera. Movable arc lights completed the camera equipment.

This idea commended itself to me. At a minimum of cost I could build this darkroom camera, and for our purpose it was much better than a bellows camera. Insects could not injure it. So I had brought the necessary materials with me, and as soon as time permitted we added two little rooms to the engraving shop. One room was the darkroom camera, the other the space for copy board and arc lamps.

Dr. Stixrud let me put an extension line from the hospital generator to provide the current I needed for the arc lamps. Our darkroom camera had another feature that made it unique, not another like it in the world. As sunlight on clear days would cost nothing, and electric current would not always be available, I made the camera reversible. Lens windows were put in front and back walls. When the lens faced outdoors I could use sunlight. When it faced indoors we could use the arc lamps. This camera would have seemed crude to professionals, but to us it seemed wonderful, for it enabled me to do at least some of the work I wanted to do. What I failed to accomplish was due to time limitations, not due to the camera.

Knowing that in America photography and engraving were so co-ordinated that a news event could be photographed and appear in the papers the same day, I wondered how long it would take us to produce a printing press picture. When the Congo Protestant Council met on our station I took a picture of the Council group in the morning, developed the negative, dried it as quickly as possible, made an enlargement and from that a half tone negative. Drying that quickly, I made the print on an enameled copper plate, and etched out the halftone picture. I had this printed on the printing press and showed it to the councillors before night. This accomplishment was lots of fun. Central Africa was going places and doing things.

There were so many things to do and so little time. It became clear that I simply must train a boy to do part of the engraving work. Because the negative making involved the use of potassium cyanide, a deadly poison, I had somewhat feared to try this. But with plenty of warning about the danger I finally took a man into the laboratory. The most dangerous work I did with my own hands. But some of the time-consuming work I began to share wherever possible.

The man learned to do line etching, but his eyesight failed, so he was replaced by a younger man of twenty. This man Kabongo became a line etcher.

As the details of the zinc etching process are very complicated I have decided to omit them, as they would weary most readers. Suffice it to say that Kabonga's labors saved me much time, and helped us to use more illustrations in the monthly paper and in school books, and even, later, in Pilgrim's Progress.

When the etching on the zinc plate was completed, with the drawing covering the ridges an over it, it was turned over to our mechanic, Ndibu, to be trimmed and nailed to a wooden block just the right height for use in the printing press. Shepati and his pressmen could then take over and print a hundred or ten thousand copies in a very short time.

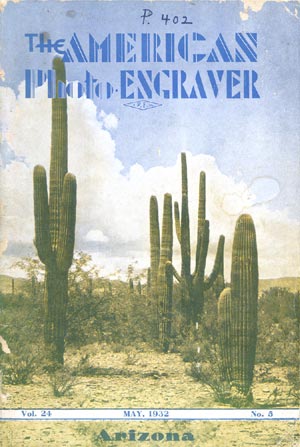

Mr. Walter Johnson, of the Chattanooga News, was an officer of the Southern Newspaper Publishers Association. Through a mutual friend he asked for information about our little engraving experiment. I wrote him in full detail about our crude little shop, with two results that came as a total surprise. First, a three-page article entitled, "Photo-Engraving in the Interior of Africa," appeared on pages 402-404 of THE AMERICAN PHOTO-ENGRAVER for May, 1932. That was the official journal of the International Photo-Engravers Union of North America. With a short introduction, the whole of my letter to Mr. Johnson was given in the article.

The second result grew out of the first. Some cartoonist for a syndicate, familiar with photo-engraving, made a fantastic cartoon of a bearded African at the etching sink examining a large zinc etching. The caption gave a brief but correct description of our work at Luebo. People in a number of states clipped the cartoon from their newspapers and sent them to me at Luebo. We enjoyed this recognition of our labors in Congo.

During this term a visitor from America reported an incident in her voyage up river. She said that their steamer stopped for the night at a small settlement. They went for a walk ashore, and as they met native people they saw a man and his wife who seemed different from the rest. She saw that they had a book, and she was interested. Some person who knew both French and English interpreted for her. She learned that the man was a brick mason, that he worked at Kinshasa. His employers had sent him up river to do some work. He and his wife were both Christians from Luebo. They had a Tshiluba Bible and a hymnbook, also copies of the Lumu Lua Bena Kasai. They gathered people together on Sundays and as best they could they told the Gospel story, and sang hymns. The woman said she cared so much for the Lumu Lua Bena Kasai that she slept with it under her pillow. We were much thrilled by this story. Many of our papers went to out-of-the-way places. The firm assurance that those printed pages were witnessing to the saving grace of Jesus Christ enabled me to carry on through long and weary hours of work, through fair weather and foul.

One of the ladies at Mutoto station told me about a boy there who could draw. He had been given a photograph of some missionary children, and made a drawing that was so good that the father recognized the likeness of his own children. I told Miss Edwards that we would very much like to have him at the Mission Press. She said he was too young to leave home. I urged that she help him as much as possible so as to prepare him to come to us later. She did this, and when she left Mrs. Miller continued to help him. Some time later he came to the Press as the artist on our staff. Tumba took criticism well, and it was a pleasure to have him around. He started making line drawings for Bible pictures, also other drawings, for the Lumu Lua Bena Kasai. I made negatives, and the engraver made zinc plates for printing the pictures.

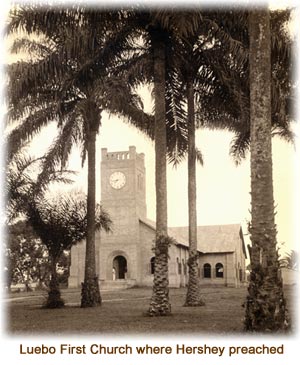

I believed in using pictures. I had made some pictures for use during our furloughs. But we wanted better pictures for the Lumu Lua Bena Kasai. Once I looked at a photo of Luebo Church made by Mr. Robertson, and wondered why it looked so much better than mine. The explanation was that his pictorial composition was so much better. When I read of a correspondence course in journalistic photography, I felt I needed it. Though we could not afford it I paid the price and took the course. It proved to be a good investment, helping me in a number of ways. From that time on my pictures were in demand at our home office, as well as on the field. Numbers of my photographs appeared in our Church papers through the years. But the course also developed my appreciation of what I saw around me.

What I saw round about me kept changing. For years our home was at such distance from the Press that I had a nice walk six times a day. For a few years I was noticing what I privately labeled my palm tree gardens. Oil palms flourished in the Luebo soil. These beautiful palms lined the paths on my way to work. I enjoyed the palms themselves (that reminds me that our Africans do not think of the palm as a tree). Wind and weather deposited rich soil between the old leafstems and the trunk. The wind or the birds planted seeds, so that beautiful ferns and tiny flowering plants of various kinds brightened the sides of the palms. In the course of months I had much pleasure in observing these tiny gardens, which seemed to be put there for my personal enjoyment. Then for many months I was watching the clouds. There are many beautiful clouds in the tropics, ever changing, and they fascinated me for a long time, and still do. With beautiful trees and flowers and clouds my mind was often refreshed as I took my little walks, largely as a result of some training in photography.

During my first term at the Press we began a project which took us ten years. It was the production of a Tshiluba hymnbook with music. Gospel singing is one of the most effective methods of spreading the Word of Life. For many years the Press had been printing hymnbooks in word editions, adding new hymns from time to time. These hymns were being sung by thousands of people in hundreds of villages all over the country. They were taught on the stations and in the Bible School, then in the village schools. But the ladies who played the organs in our Churches had a hard time keeping up with the various hymnbooks containing the music. Often they had to carry a Tshiluba hymnbook with words, and from one to three hymnbooks with music, when they went to Church. Some had their own rather clumsy scrapbooks with hymns clipped from hymnals, and Tshiluba words pasted in. All of these were unsatisfactory. I wanted to do something to help them. As a sort of hobby I started to make photo-engravings of hymns with music and the Tshiluba words. It was understood that during furlough I would try to improve my knowledge of photoengraving. So after I was in America I received a letter asking whether, while practicing, I could etch some hymns that could be used on the field. Mr. McMurray took more than 200 hours of his precious time to make drawings of 32 hymns, with Tshiluba words printed in, all done double size for reduction in making the negatives. These reached me in due time. My good friend Mr. Raymer agreed for me to work in his own little shop near his house. I had just started work on the hymns, and one night left the suitcase containing the music drawings in his shop when I went to my lodgings. When I rose in the morning my landlady said she had bad news. Mr Raymer's shop had burned down that night. I was very sorry for his sake and for mine, and also for losing all that painstaking work Mr. McMurray had done. I went to the shop to look things over. The frame building was destroyed, with much of the equipment. Looking for the suitcase we found the steel frame with the ashes in the bottom. Stirring in the ashes with a stick, I was surprised that many of the cards with hymn drawings had not been burned. Some were entirely burned, some in part. But sixteen hymns were intact, though burned around the margins. It was decided to have these done at a professional engraving shop before anything else happened, and this was done. So half of Mr. McMurray's work was salvaged.

On our return to Luebo we tried to get on with the job of making the drawings and producing our own plates. It will be recalled that these were depression years, and money was very scarce. We were pinched for funds in all departments. So if we wanted a music hymnal we had to do it at Luebo.

It was found that our artist Tumba, who also had musical talent, had learned to play both organ and piano. He could make music drawings, and thus save much missionary time. Besides his work as Press artist, he was employed making these drawings of the music. The printers set up and printed the words to be pasted between the lines of music, then ready to be photographed. By this time Kabongo had a helper in line etching. I made the music negatives, they printed them on zinc and etched them. Our work went very slowly because I had so many other irons in the fire. By working as best we could for ten years we finally printed 240 hymns with music in our hymnbook. The book has been reprinted a few times. We feel rewarded for all our efforts because hundreds of natives have learned to sing by note, and are able to teach others. Many Africans have wonderful voices and love to sing. Under the talented instruction of Mr. McMurray at the Bible School there has been great improvement in hymn singing throughout the Mission. Dr. Fulton is reported to have said, "Many of these Africans will sing, themselves into the Kingdom."

Having again mentioned our artist I might as well tell the rest of his story, some of it going beyond our fourth term and into the fifth. He was with the Press, I suppose, eight or ten years. More and more I depended on him for drawings to be used in the Lumu Lua Bena Kasai, in school books, and, in other ways, besides the music drawing which was slow and exacting work. Mr. McKee had translated Pilgrim's Progress into Tshiluba. He had found a Swiss translation which carried many small illustrations. We obtained permission to adapt these for our own use. In this way Pilgrim's Progress was illustrated with drawings of African characters throughout. John Bunyan might have been surprised to see what some of his characters looked like.

Other drawings by Tumba have been used through the years, and I suppose are still in use. He rendered a service of permanent value.

But Tumba, while he was one of my best helpers and one of my best friends, was also my greatest worry. He came from a Christian home, was highly talented, and had refined sensibilities. His personality compared to the average of his people somewhat as a spirited Arabian race horse might compare to a Belgian dray horse. But he was temperamental, as artistic people sometimes are. Here was my problem. He and I got along just fine, and understood each other. But he often got in trouble with other natives. I think it was partly that they recognized that he was gifted above their class, and were jealous of his superior talents. Whatever the reason, he got into trouble here and there. I highly appreciated his skill, and did not want to lose him. But things reached such a state for some years, that when I sat at home reading in the evening, and heard a quiet cough on the porch, I feared it must be Tumba come to tell me he was in trouble again. I shall enumerate only a few of his many troubles. Once a boy attacked him with a knife. Tumba had been giving music lessons to a mulatto girl, and sat on the same bench with her at the piano. The brother of Tumba's assailant was engaged to this girl, so he felt it was his brotherly duty to get rid of Tumba. Most other scrapes were less serious, but always they worried me, and took some of my time and energy. Once it was reported that a man nearly shot Tumba, when he found him staring into the family bedroom at midnight. Tumba claimed that he just happened to pass by on his way home. But it took real begging to save himself from the wrath of the man with the gun.

We found an assistant artist who had much talent, and was a great help. He died later with tuberculosis. A third talented boy was found, and Mrs. Wilds gave him some art lessons. When he reached the stage where I could employ him, I sent him to the hospital for a physical check-up. Dr. Stixrud in looking at some of the boy's papers found that he had been practicing quite skilfully to forge the signatures of some of the missionaries. So it seemed unwise to employ him. So Tumba remained our mainstay in the art department, and I feared lest one palaver too many would take him from us. Finally it came. Tumba had married, had a new hut, and a baby came to bless their home. I had hoped his troubles were over. But I was mistaken.

One day Dr. Martin told me that either my man Tumba was a bad man, or he was crazy. He reported that the night before there had been excitement in the village. A man had been seen lurking in the shadows of some palm trees a mile from Tumba's home, staring at a hut occupied by three unmarried girls. It was bright moonlight. Someone challenged the peeping Tom, and he jumped out of the shadows and ran for his life. A wild chase ensued, and as the pursuers were passing through the street of the Bakwa Kalonshi, the man was caught. It was none other than our Press artist Tumba.

The Press could not compromise its good name even for a skilled artist. So I let Tumba go, with great sorrow in my heart. We never found his equal, so our work suffered accordingly.

Our work was growing. I needed a better office for my own work, and for our shipping department. We also needed a large termite-proof room for storing books and paper. So the money was secured and a new building planned. Mr. Hugh Wilds kindly agreed to make the bricks and erect the building. There was to be a roomy office for me, away from the noise of the presses, also an office for our copyist and shipping clerk Mukendi, and a shipping room. The large stock room was to have a cement floor. All book and paper stocks were to be stored on shelves suspended from heavy overhead beams. There was to be eight-inch clearance between all shelves and the side walls. With the clear floor space and clear side walls one could inspect the whole large room in three minutes to make sure the termites were not starting anything. So far as I know none of the stock in that room has ever been touched by termites. And if you know your African termites, and their appetite for paper, you will know that is remarkable. (One of the missionaries told me that termites started on his commentaries and ate right along until they came to the doctrine of predestination. That was too much for them.)

During these years our daughters were at our school for children of missionaries at Lubondai, about 180 miles from Luebo. Those unfamiliar with the history of Congo Missions can hardly appreciate what that school meant to us. When we went to Congo it was the common practice for missionaries to leave their children in the homeland on the first furlough after their birth. On some Congo Missions that is still the custom. But our missionaries felt strongly that they were responsible for the rearing of their children, and must keep in touch with them. So a small school was started, and grew to about fifty students from fourth grade through high school. All faculty members are college graduates, and most of them volunteer for one three-year term. An excellent succession of consecrated teachers has been an inspiration to our children and a great comfort to their parents. The school is integrated with the American school system so that children can spend the furlough year in their proper grade in America, and return to fit into their own class at Lubondai. When they graduate from Central School they are ready for college in America. No family has profited more from the establishment of this school then we have. Our three children received their basic education there, and loved it. Both by teaching the children and by releasing their mothers for other forms of missionary work the Central School teachers have made a very important contribution to the Lord's work in Congo.

It should be explained that the first three grades are taught on their home stations, usually by their mothers, but sometimes by others. Mignon, having been a teacher before our marriage, taught our own children these three grades, and also taught children of other families so the mothers could be released for other work.

The school year at Lubondai consisted of two terms of 4 months each, with six-week vacations. Thus the parents could be with their children twice a year. We rarely saw our children except at vacation time. During one of the vacations of Central School, we usually took our one-month vacation with them at Lake Munkamba, a beautiful lake in the heart of our Mission's territory. Here our children, like most of the children of the Mission, learned to swim well, and spent much time in the water. Most Congo waters have hippos and crocodiles to make bathing hazardous. But Munkamba is a safe and quiet place, and the water is free of the germs of tropical diseases which are all too common in Central Africa.

Once we were returning with the girls from Central School in a Model A Ford sedan. The road was very dry. We came to a place in the forest about 100 miles from home where the road up a steep grade had been dug up, and was little more than a deep bed of sand. Running into the sand, the motor stalled. Trying to start I must have flooded the carburetor. Time after time I tried and failed to start. With embarrassment I agreed for Mignon and the girls to get out and push. As she got out Mignon announced that there was fire under the hood. Cutting off the gasoline flow from tank to carburetor, I got out and opened the hood. Sure enough, the carburetor was burning. It has been my only experience of the sort, and I didn't know what to do. As nothing else was available we threw handfuls of sand on the fire and put it out. I have been told since that we could have found nothing better. We looked around and found a small underbrush fire in the dry forest, close to the car. We concluded that when the carburetor flooded, fumes of our gasoline had connected with the forest fire which then flashed back to the carburetor. We were so thankful none of us was bummed. However I feared the car would not run, with home a hundred miles away. To our great surprise and delight the motor started, and when we got out of the sand we drove right on home.

But furlough time came, and our girls had to say goodbye to Central School and to Congo. They loved the land of their birth and would have wished they could get their college education at Lubondai.

The five years were tilled with hard but rewarding work. The output of hymnbooks, catechisms, Bible commentaries, school books and periodicals was growing, and it was quite clear that we needed more equipment. The Mission authorized me to try to find the money and buy this equipment during furlough. So we left for America with high hopes.