On our third trip into the Congo we again entered through Matadi and Leopoldville. We went up river on our own Mission steamer Lapsley. A sad but memorable experience of the river trip must be mentioned. As we were passing the little post of a Danish trader on the Kasai River, he signaled to our captain to come to shore. So Mr. Wilds anchored near his place. The trader came aboard and explained that he lived alone with his native help. The day before a Belgian had been hunting upstream. He wounded a hippo, which then attacked and destroyed his canoe, and killed the hunter. The employees of this Belgian carried their master's corpse to the Danish trader's post, then ran away, leaving the problem of burial to him. But his own workmen were superstitious, and would not lift a hand to help him. He could not bury the man alone. Would Captain Wilds kindly lend him the steamer's crew for the interment? So our journey was interrupted. A rude coffin was quickly made, and neatly covered with cloth. It was draped in a Belgian flag, and one of the missionaries conducted a funeral service. As a comfort to the family of the deceased in Belgium I took a photograph of the coffin and grave, and sent it through a local official to the man's parents. In due time I received a nice letter of appreciation. By the time for the burial, news had gotten around, and quite a number of white people gathered. Someone counted that the deceased was the only Belgian present, but that there were people of six other nationalities. He was a Roman Catholic, but Protestants conducted his funeral. Congo, then under the Belgian flag, had quite a cosmopolitan population.

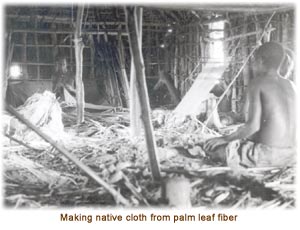

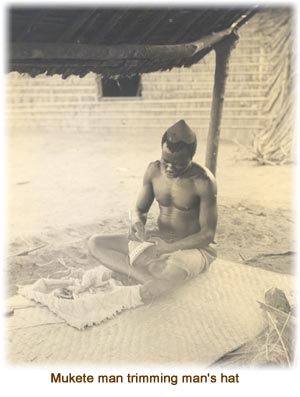

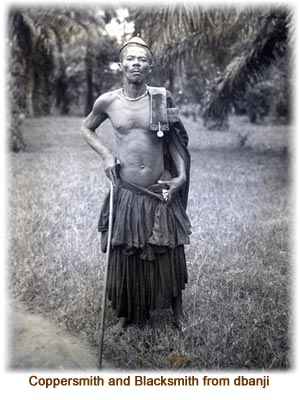

While awaiting my assignment by the Mission I did some itineration. It was an enlightening experience. Three things I had previously heard about the Bakete tribe. One was that their marriage customs were very bad. A second was that when the Mission started its work among them many years before, they had responded so poorly to the call of Christ that the work grew away from them. Their language was dropped, and the Mission adopted the Luba-Lulua tongue which is now called Tshiluba. The third was that the Bakete were a lazy people who did not like to work. My visits to their villages proved that they were not so lazy as I thought. True, they did not care to work for white men. But living their own lives they were quite industrious. They were skilful weavers of raffia cloth. They raised raffia palms around their villages, cut the fibers and prepared them, then wove them on crude little looms into squares of cloth. This cloth could be beaten into something much softer than ordinary palm fiber cloth. Sometimes it was woven into beautiful patterns, with or without color, and sewed into long rolls which the men most carefully draped around their persons. It took a Mukete man many minutes to put on his ceremonial dress. Their arts were similar to those of the Bakuba people to whose king Lukengu they paid tribute. They not only made cloth. Their blacksmiths and coppersmiths were very skilful in making swords, spears and arrows of graceful designs, beautifully decorated. They wove neat little conical brimless hats which the men wore with cute homemade metal hatpins. I was told that a young man was not allowed to marry until he had learned to weave cloth, and to build him a house. These huts were different from those of most tribes. Both the sides and the roof were of a woven sectional construction, made in five or six parts, one for each side, and one or two for the roof. They were quickly set up, being tied to posts in the ground, then tied together at the corners, and the roof was tied on. They were even more quickly taken down. More than once I have gone to a Bakete village, and found it was not there. Where was it? It could be found across the road, or some distance away. Moving a Bakete village is only a matter of days. If they get tired of one site they move to another. So my itineration greatly increased my respect for the industry and skill of the Bakete. Also I was glad to learn that more of the Bakete were accepting Christ. Later I found that when they became Christians they were often more liberal in their giving than were other tribes. My visits among them brought me no respect for their marriage customs. Most other tribes had a system of marriage dowries which were designed to stabilize marriages. When a man paid 15 or 20 goats as dowry to the wife's family he would not hastily abandon her and lose his valuable goats. On the other hand the bride's people would not favor her running away from her husband, for they would have to repay all those goats. Among those other tribes the man was the head of the house, and the possessor of the children, who were lost to the mother if she deserted her husband. But not so the Bakete.

Among the Bakete practically no dowry was paid. Women did very much as they pleased. Marriages were quickly made and quickly broken. In this matter Hollywood is merely following the Bakete. Often it was the woman who broke the marriage. If a Bakete marriage was broken she took the children. Many women would have been ashamed to admit that they had lived a whole lifetime with the same husband.

On this same trip, while we examined the professing Christians before communion, we learned that two men, by consent of the four persons involved, had agreed to swap wives, and it was done. After some time they decided to swap back again. So husband number one was living with wife number one, and husband number two was living with wife number two, as in the beginning. But trouble had arisen. Husband number one found that husband number two had given a gift to wife number one, and he was jealous. He thought perhaps they were not living straight. The ensuing quarrel brought out the ugly facts.

Perhaps it is in order to say a few words about our Mission organization. Mission government usually has its roots in the form of government of the sending Church. That is not always so. We have heard of missions sent out by Churches of the independent type, where the government on the field was almost autocratic. But as our government at home is Presbyterian, and all our missionaries on the field are on a basis of equality, the decisions are made by vote of the majority in the annual Mission Meeting. Local station matters are decided by vote of the majority of station members. We have no superior officer. Chairmanship of the Mission changes each year. Much work is done by committees, which bring recommendations to the Mission for acceptance or rejection by majority vote.

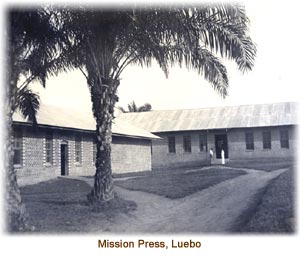

My work assignment had to wait until the annual meeting at Bulape. For years I had overtured each annual Mission Meeting to make the Lumu Lua Bena Kasai a monthly instead of a quarterly publication. Because I so keenly felt the importance of this matter the Mission assigned me to the Mission Press to accomplish what I believed in. I was told we could publish the paper monthly as soon as we finished printing a stack of manuscripts that had been accumulating for some time.

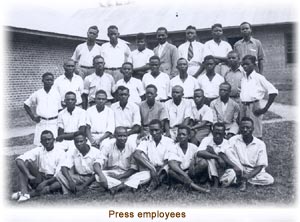

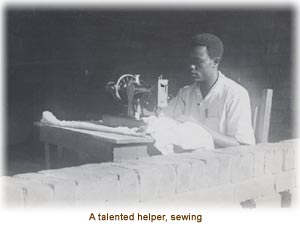

All I knew about printing was what I had learned as a boy playing around with a 3 x 5 inch hand press and a small quantity of type. I did not receive any instruction. When I took over the Press it appeared that the little I did know was all wrong so I based my plans on what they already knew. Occasionally through the years the Press had been in charge of real printers, so about five of the men knew more about printing than I did. It was clear that I need not set type nor feed presses myself. The whole problem was one of management. As my education had included cost analysis and estimating, I set to work to find a way of increasing production without raising unit costs. The other missionaries cooperated in persuading a few former employees who knew the work to return to the Press. Dr. Motte Martin was very helpful in this. For the time being I continued to pay the men as they had been paid, by weekly food allowance plus monthly salary.

I took my time checking things over. One serious blunder could wreck all my plans. After much careful calculation I found ways by which we could have an adaptable piece work system. Then the men were told that we would begin paying them according to work accomplished. Our objective was two-fold: To increase their earnings, and to speed up production. The men did not want it. They wanted more salary but not on those terms. It took insistence upon the new plan to get it started. But after it was in effect individual earnings picked up so decidedly that in a short while jobs at the Mission Press were in demand. We had more capable applicants for jobs than we could use.

It took us six months to clear up the waiting manuscripts, then we were ready for monthly publication of the Luma Lua Bena Kasai. That was a red letter day in my life, for that had been my object in taking over the Press.

Space at the old Press building was entirely inadequate. There was money for a new building, but no one available to build it. So I was persuaded as a sideline to make bricks, and manage the masons and carpenters for erecting the new building. Men with experience could be found in the village, so building was much easier than it had been at Bibanga. Nevertheless this sideline gave me more work than I should have attempted to carry in the tropics. The Lord helped me get the job done without a breakdown.

When the new building was finished we had to move. Moving the old flat-bed hand-operated press was not easy. We had to take it apart, move the pieces, and reassemble it in the new building. We had a distinguished visitor at the time. He found me under the machine with my shirt off, all black and greasy.

There was a new press already on the ground, in its original packing cases. That, too, had to be assembled. I knew nothing about this press, but I did know how to read blueprints and instructions for assembling, which came with the press. Those helped me very much. Handling the heavy pieces and assembling them was a big job. By and by the new press was ready for work. After that we had to install the gasoline engine and a line shaft for operating the new press and a job press too.

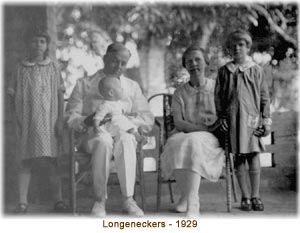

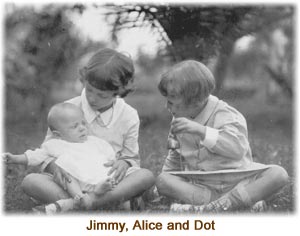

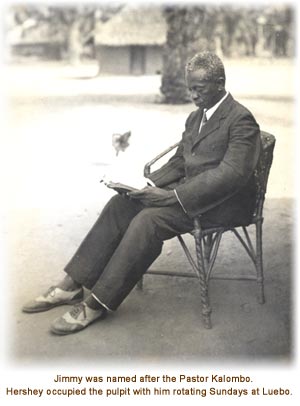

In the midst of our busy years our son Hershey James was born. We were happy to have a son in the family. He was baptized by the pastor Kalombo, a fine old man who had preached many years at Luebo. We were pleased when the people named our son Kalombo after the good old minister. Before the baptism Kalombo told me he felt like John the Baptist must have felt before he baptized Jesus.

Expecting to be reassigned to Bibanga I had brought out a truck chassis for evangelistic itineration, and materials for building the truck body. At the beginning of this term I built it. It had room for baggage at the back, and two seats all the way across for us and our passengers. At night the backs could be laid flat to make a double bed, with the seats. I greatly desired to preach in other villages, but it was hard to get away from my work at the Press. Whenever I could get away I arranged week-end trips, going out on Saturday afternoon, and returning Sunday night or Monday morning. Quite a number of times I visited the village of Mweka, on the new railroad, some forty miles from Luebo. It seemed destined to become a large town, as people of many tribes moved in to work there. Some of them were Christians, and they were glad for visits of their missionary. As the truck was enclosed for sleeping, I could camp anywhere. Government regulations forbade a white man sleeping within the native people's part of the town, which was designated as a "circumscription urbane." So in the evening I went elsewhere, and returned in the morning. One night I spent in my car by the roadside, some distance from any town. Though alone there, I did not think I was in any danger. Shortly afterwards I learned that while I slept there alone, the corpse of a murdered Negro lay in the forest nearby. If I had known that I would not have slept so well.

One year we went for a vacation trip to Bibanga, where I preached during the conference for evangelists. This was the kind of work I really wanted to do, and I enjoyed it. Also it brought me in touch with distant readers of the Lumu Lua Bena Kasai.

On the return trip we had a memorable experience. We were about halfway between Bibanga and Lubondai stations when the truck rolled to the side of the road, and stopped. A front wheel had come off, the king bolt having broken. Unless I could find some way to replace the bolt we might be there for days. At that time automobiles were few, and it might be days before another car passed that way. Miss Larson was with us. She suggested that I might cut off a piece of an iron rod at the end of a seat. Fortunately I had a hacksaw, a flat file, and a small vise. Cutting the rod to proper length, I began to file it down to size. The car could not be moved out of the hot sun. The ladies and children found a bit of shade under a tree. But the vise had to be attached to the back of the truck, so I had to work in hot sun. There I filed from two o'clock until six. My job was nearing completion. A little more filing, and I could insert my substitute for a king bolt, and drive our truck very slowly 60 miles to Lubondai. There would be some risk of a breakdown.

Then someone saw a car in the distance, and we were in suspense to see whether it might be a Ford. It was. We asked the strangers whether they happened to have a spare king bolt, though it seemed unlikely. They said they were sorry not to have one. They were on their way to Dibaya, on another road. If they found a bolt there they would send it back by foot messenger. As that would take two hours or more, I stopped filing, and we prepared to eat supper. I was tired of filing anyway. Before we finished supper we heard a car, then the men arrived. They had gone to Dibaya, found a bolt, and without getting their own supper they came to help me fix the car. We were filled with gratitude to these strange men for help so graciously given. They certainly were angels unawares. About midnight we pulled in to Lubondai station.

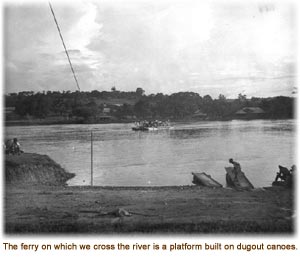

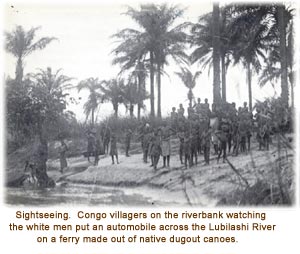

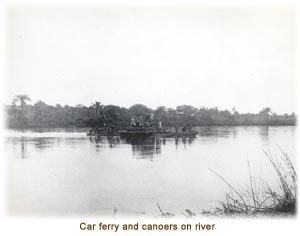

We once received a request for help from Mutoto station. They had some babies who were fed on tinned milk. A lot of milk had arrived at Luebo. Would somebody bring it as far as Luluabourg, where their porters could get it? So I loaded our truck with cases of tinned milk. The Luebo ferry had no cable at that time, so it was a hard job crossing the river and sometimes took an hour. I wished to reach Luluabourg before dark next day, so decided to put the loaded truck across the river, in the afternoon, come home for the night, cross the river in a canoe before daybreak, take the truck and go to Luluabourg. The ferry was nothing but four dugout canoes with a platform built over them. Two heavy planks served for driving the car onto the ferry. A rope tied the ferry to a post on shore. But as I was driving onto the ferry one of the planks cracked, and a back corner of the truck body nearly touched the water. Quick action was imperative. The fastening of the ferry was precarious. If I returned to the station for planks and help I might find the truck in the river and the ferry lost when I returned. It would have been an awfully hard job to get that truck out of the river. Best thing I could think of was to take cases of milk out of the truck, and use them for. a base for jacking up the broken plank. That work must be done in the water, and both the wooden cases and I would be soaked. But if the truck fell in, all the cases would be wet. Presuming that no crocodile would bother us, we set about our task. It took two hours work in the water before I finally had the truck safe on the ferry. The ferrymen poled and paddled the ferry across. I returned home for the night, and next day made the trip as per schedule.

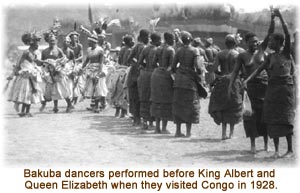

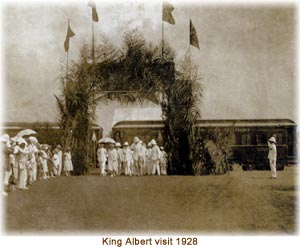

In 1928 the long awaited railroad from Port Francqui to Elisabethville was completed. It linked our part of the world with the Cape-to-Cairo system projected by Cecil Rhodes. This great event was celebrated by inauguration ceremonies honored by a visit from King Albert and Queen Elisabeth of Belgium. There were two special trains, one carrying the King and Queen, and their retinue. The other train carried invited dignitaries and journalists. Our Legal Representative was invited. Dr. Motte Martin had returned from furlough, and while he kindly urged me to go as representative of our Mission, we all knew that he should go, and he did. But the rest of us were invited to see the King and Queen when the royal train stopped at Domiongo. The King of the Belgians was to visit one of his subject rulers, Lukengu, King of the Bakuba. This was a noteworthy occasion.

The Bakuba people are one of the remarkable tribes of Africa. It is probable that no African tribe south of Egypt has such highly developed and such distinctive native arts. Many fine samples of their work are to be found in the museum at Terveuren near Brussels, and in the British Museum in London. They do magnificent raffia work, and very fine bead work, make a unique type of mats, and their smiths do wonderful designs in iron and copper. Each succeeding Lukengu has his individual pattern which is woven into his mats and raffia cloth and tapestries. It is also wrought into his metal work. One Lukengu had chosen a pattern found on the treads of one brand of American automobile tires. From the time the new Lukengu ascends the throne until the time of his death, hundreds of the women in his harem, and many skilled men, work upon priceless tapestries and costumes for his burial. When the king dies he is buried in a great grave perhaps sixteen feet square and sixteen feet deep. He is seated in all his finery in the middle of an immense coffin richly decorated, and the coffin is surrounded by many cases and bundles of the finest products of the kingdom, including large tusks of ivory. All of these are visible during the ten-day funeral, then are buried with the king. The general public is never admitted into the great harem nor to the private quarters of the king where these art treasures are kept, nor yet to the royal funeral. So only favored persons, including missionaries, ever get to see these things.

The coming of King Albert and the Queen was something unprecedented, so the custom of the years was broken, and King Lukengu appeared in all the finery prepared for his burial. Three large pavilions had been erected, one for the royal couple from Belgium, another for Lukengu and his courtiers, and a third for the guests of honor from the second train. The rest of us were just observers on the side lines. The Bakuba were all decked out in their finest native regalia. It was absolutely forbidden them to wear a single stitch of foreign clothing on that day. Nearly all the white visitors were dressed in white.

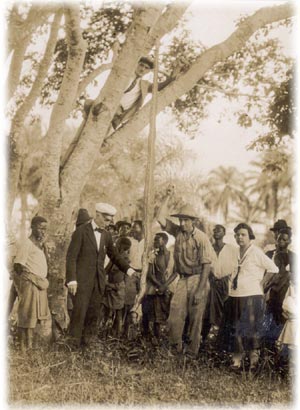

King Lukengu was paralyzed, and could not walk at all. So he sat in state in his royal pavilion where his sovereigns from Belgium went to call on him. Royal gifts were exchanged. I have forgotten what King Albert gave Lukengu. Among other precious things, Lukengu presented King Albert with the biggest mats I ever saw. After the royal greetings the King and Queen returned to their pavilion. Then began the most spectacular dances I have ever seen. To the music of Bakuba drums the elite of the kingdom danced for the King and Queen. It was a day to be remembered.

This might be a good place to say that some years later a number of us missionaries were privileged to attend the funeral of this same King Lukengu. We saw the corpse lying in state, the great coffin and the gigantic grave, and the bundles and bundles and bundles of things that were to be buried with the king, many of them doubtless the same art treasures which had been exhibited at the royal meeting at Domiongo. Any great museum in the world would pay a fortune for the magnificent finery that was buried with Lukengu.

But we mentioned the inauguration of the railroad. Since that time it has brought great changes to the Kasai region. The seat of government of the Province of Kasai was moved from Lusambo to Luluabourg. What within my own memory was a cornfield has become an important city, with railroad service, a network of bus lines connecting it with cities of the province, and an airport from which one could fly to Johannesburg, Elisabethville, Leopoldville, Brussels or New York. There were passenger trains in two directions twice a week, and telegraphic communication with the outside world. The railroad has connections at Port Francqui with steamers for Leopoldville, on Stanley Pool. The railroad brought in many foreign products, including automobiles, trucks, tractors, and gasoline. It exported cotton, corn, peanuts, cooking oil, palm nuts, beef, copper and diamonds.

A telegram announced that Dr. and Mrs. Cousar of our Lubondai station with their baby daughter would arrive at Port Francqui Friday. So it was decided that I would meet them with my truck. It was nearly a one-day trip. When I arrived I went to the steamship office for the latest information. They said the steamer I named was not coming up the Kasai River at all, as it had gone up the main Congo River. This was most puzzling. Certainly Dr. Cousar would not have called us up there without reason. I said so. The man then told me that even if the steamer were coming to Port Francqui, it could not possibly get there before Monday. This was Thursday evening. As I did not wish to travel Sunday, there was no use in going to Luebo Friday, and returning Saturday. I might as well stay at Port Francqui and wait, though I hated to waste three days. At that time there was a Ford agency at Port Francqui. I went there and asked whether they had a certain differential gear which I wanted to put on my truck to step up the gear ratio. They had the gear I wanted, and offered me working space to make the change-over. So Friday morning I began to disassemble the differential housing under the truck. I began jacking the truck up as high as possible, I worked on a tarpaulin underneath. By sunset I had it all apart, and was ready for the new piece.

After supper there was nothing to do, so I went to sleep in the truck. Just as I was nearly asleep I heard a boy calling me. He said the doctor was at the steamer. I jumped up and asked permission to work all night in the garage. Then I got ready for work. About that time Dr. Cousar arrived. It seemed they must leave the steamer next morning, and there was no place to go but Luebo. Dr. Cousar offered to help me with the truck. Port Francqui is a warm spot. Also it has a reputation for its fine crop of mosquitoes. We worked through the night under the car without our shirts. We slapped mosquitoes all night with our greasy hands. Long before morning we looked as if the Black Hand society had been working all over us. About 10 o'clock we had the car assembled. It was not a perfect job. The housing joint would not close perfectly. After we got to Luebo we took it apart and found we had overlooked a tiny lug that should have fitted into a particular hole. But the truck would run, so we loaded it and had lunch.

At one o'clock we were on our way. It will be noted that it was now Saturday afternoon, and we had had no sleep since Friday morning. We thought that by relieving each other at the wheel we could drive through to Luebo before midnight. But parts of the road were new, and far from good. Once we hit a sandy place where I was unable to hold the truck in the road. Deep sand on one side pulled us into the ditch. To get out of the ditch we had to unload a ton of baggage. We did that, got the truck back on the road, reloaded, and started again for Luebo. We had to drive carefully to avoid being ditched again. We were awfully sleepy. But there was no place to lie down, and we couldn't sleep sitting up. So one of us would rest half awake, and the other would drive half asleep. All Mrs. Cousar and baby daughter could do was to put in the time. It must have been a terribly long night for them. We drove slowly all night, and reached Luebo at eight o'clock Sunday morning. I went to bed for the day.

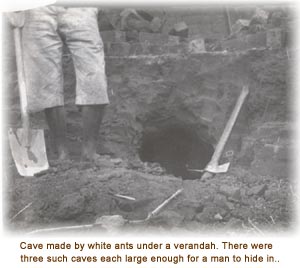

While attending our annual mission meeting at Bulape, Mignon and I slept in an unscreened house with the windows wide open. We thought nothing of this until we waked one morning to be told that a big snake had stolen a baby goat out of the back yard during the night. This would be a real thrill, so all the missionaries were called, and with native guides we followed the trail of the snake to an old anthill. These anthills when broken open reveal a good-sized cave beneath, from which the termites removed the earth to build the superstructure. There was a hole at the side, and the big snake had gotten part way in. The hole was too small for the bulge made by the baby goat. So the rear half of the snake was still outside. The men made a noose out of a strong vine and slipped it over the tail. Some of us pulled with all our might while others were belaboring the python with clubs, and still others were digging with picks and spades. Little by little he was pulled out, until his whole length was exposed, with a big lump in the middle. The python was 13 feet long, the largest I have ever seen. Dr. Chapman of Bulape later shot one in the nearby forest that was more than 19 feet long.

Once we were on a trip to Lake Munkamba with our family. The Model T truck did not have a water pump. But I had bought and installed one. On this trip we happened on a five-mile strip of new road that was like a ploughed field. Running on low gear the motor became very hot. The hose which came with the pump burst, all the water ran out of the radiator, and we were grounded. I called for a foot messenger to run to Mutoto station to borrow a piece of hose. He could probably get back in 36 to 48 hours. In the meantime we were parked out in the tall grass a mile from a village. A great crowd came out from the village to see the show. I asked some of them to bring us water and firewood, so we could cook our supper and camp for the night. But nobody stirred. If they went hunting wood and water they would miss the show: one white man, one white lady, three white children. I expected and offered to pay for help received but there were no volunteers. I do not mind being looked at, but did not like to go to bed hungry while they watched us. So I called the chief and told him he was responsible to make his people help us. If he failed to do so I would report him to the government. Certainly the government would not tolerate such a situation as this. This was effective, and with the assurance that they could watch the proceedings when they came back the people scattered, and soon we had a pile of firewood, by and by the needed water.

Meanwhile I had beaten my brains to see whether there might possibly be some way to repair that badly broken hose. I did have some tools. An empty oil tin was found, and a shears with which I could cut a piece of tin. This I washed well, rolled it into a tube, soldered it, put it inside the broken hose, and wired it together. In this way we were able to drive on to Munkamba without the new hose from Mutoto.

Daughter Dot thought it wasn't much fun to go on a trip unless something exciting happened. She was with us on a trip to Bulape station. Having heard that the bridge over the Lekedi River was getting weak, I asked Mr. Washburn about it. He said it would hold the truck if I drove slowly. I did just that. Also I played safe by having the family walk ahead to the other side. But when the truck was two-thirds across there was a crash, and the back wheels had broken through the bridge. I called a lot of men from a nearby village. They cut timbers for use in prying up the rear of the truck. We worked four hours, and finally at sunset I was able to drive off the bridge. While I was examining the bridge in mid-afternoon another timber had broken. I dropped six feet to a sitting position in six inches of water. Mignon asked Dot what had happened. She replied, "Oh, it was only Daddy."

During our second furlough Dr. Huston St. Clair had given me a fine new Winchester rifle and a thousand rounds of ammunition selected for use with various kinds of big game. This would have served me well if we had gone back to Bibanga. But at Luebo there is little game for hunters. One evening we had Dr. Motte Martin to dinner. He told us some interesting experiences, including the story of a hippo hunt by moonlight, right down the hill between us and the river. It had taken place years before. The climax of the story was that when he was ready to shoot the beast charged and nearly outran him. He escaped with his life, but carried away no glory from that encounter. He was a notable hunter of monkeys.

Mignon was much impressed by this hippo story. She also recalled my hippo hunt at Bibanga. Then there was also the memory of the Belgian hunter who was killed by a wounded hippo, the one we had helped to bury as we came up river. You will see that this combination scored against me as a hunter.

Strangely enough, it was just a few days later that natives came to beg me to shoot the hippos which had begun to destroy their cornfields near the river. Here was the big chance to use my rifle. But just at that time Mignon had her mind all set against hippo hunting. She had two unanswerable arguments. One was that the Church had sent me out at great expense to do missionary work. Secondly, I was a husband and father with responsibilities, and had no right to take risks with my life. She won the argument, so I decided to give away the gun and ammunition. My work at the Press so occupied my time and thought that I wouldn't get to hunt much anyway. Our good friend Roy Cleveland made a wonderful record with that gun. In the course of time the stock was lined with rows of notches, some for antelope, some for hippos, some for crocodiles and some for buffalo. He lived in game country, did much itinerating, and anyway he was a much better hunter than I ever could have been.

On a trip from Lake Munkamba to Luebo we decided to travel at night, so the kiddies would not get so hot. I rarely permitted passengers to remain in my car when driving on or off ferries, as there is always some risk. But on this night as we were about to cross the Miau River, which had one of the best ferries, the baby was asleep. So we decided that the girls and our Congolese passengers would get out of the truck and ride on the ferry platform, then get off ahead of the truck on the far side. Mignon and baby Jimmy would stay with me in the closed truck. When we reached the other shore and the girls were safely on land, the boatmen placed the planks before the wheels, and I started the truck. The front wheels went up the planks. But plunk! The back of the truck bumped and stuck. I almost screamed to Mignon to hand me the baby, and come. I stepped off the ferry -it was dark -onto what I thought was solid ground. I fell down, standing, into a lot of tree roots where the ground had washed out. I tore my trousers and hurt my knee, but was happy the baby was not hurt. When Mother and son were safe ashore with the girls I checked up to see what had happened. We had a close call. The boat must have shifted position as I drove off. Front wheels were safe on the planks, but the rear wheels were astraddle of one of the planks, hung on the differential housing. The supporting plank hung on the ferry by just 2 inches, and was not fastened at all. The only thing that saved the truck from dropping into ten feet of water was that the plank sloped toward the ferry, not away from it.

Here was a chance for some engineering. What a job it was! For the first hour the boatmen nearly exhausted my patience by making counter suggestions to nearly everything I tried to do. Having tried some of their ideas only to fail, I decided it was better to follow my own plans. By faith and works we at last had the truck on solid ground, and we were indeed grateful to our merciful Heavenly Father that Mignon and baby and I had not been drowned, leaving two young orphans on a riverbank a hundred miles from home.

We started for Luebo about two A.M. By and by we broke a front spring. We had a spare, and set to work making the change. It was still night. Something or other slipped, so that when the spring was in place the radiator hose connection was broken. So that had to be fixed. All this happened in the dark, with the unsatisfactory light of a kerosene lantern. Mignon was worried because we could hear a leopard down in the valley.

These various experiences were merely brief interludes to a lot of hard and absorbing work at the Mission Press, which was the compelling interest of my life. The Lumu Lua Bena Kasai was being printed every month. The Sunday School lessons by Mr. Allen were reaching all our hundreds of villages. Our output of other printed matter for the schools, the hospitals, and the evangelistic department was satisfactory to the Mission. As our furlough approached it was arranged that Mr. McMurray would take over my duties during furlough, with some help from other missionaries with such mechanical problems as might arise. We were ready to start on our third furlough. The Ford truck had been given to one of the stations. I did not like it to stand idle, nor for the Lord's money to be wasted.

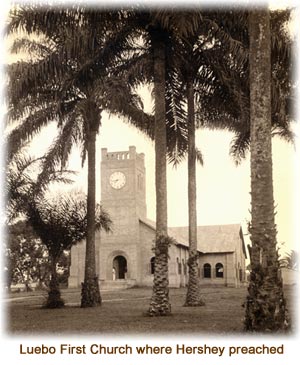

My opportunity to preach had been given me right there at Luebo. While I did preach elsewhere too, I had begun to preach at Luebo First Church every other Sunday morning, alternating with my good friend the pastor Kalombo, previously mentioned. He was a most worthy Christian and a real pastor. This was the largest congregation on the Mission. There were two other congregations in Luebo, but we still had an attendance at First Church of from 700 to 1500 worshippers. Communion service was held every two months. It was always a heart-touching experience to me. Admission had to be limited to Christians in good standing, but even so the big Church would be crowded to the doors. Sometimes communion was given to groups outdoors for whom there was not room in the Church.

It must be understood that the pastoral work for so large a congregation was very heavy. That had to be left to my fellow missionaries and the pastors and elders, as I was busy six long days per week at the Press. But my own soul was refreshed by the preaching of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, who loved me and gave Himself for me. Refreshing also was the attendant Bible study as I prepared my sermons.

I have always believed in preaching, and while I had not in the beginning desired to be a preacher, it is also true that after the first few years in the ministry I loved to preach. But I was convinced that my greatest opportunity for spreading the Gospel lay in the printed page, and my editorial work in encouraging other preachers in their ministry.

We had reached the end of our third term.