The labor situation in Congo was difficult during our term at Bibanga. International exchange had played havoc with the value of money. Industry had not yet adjusted to it. The men who wished to work for the foreigners had all the jobs they wanted. But there were not enough men to meet the demands. The government put into effect what amounted to a rationing of labor. Foreign employers asked for the help they needed, and government officers called on chiefs to provide the needed men. A case in point will show what happened.

Bibanga station had at Lusambo, 160 miles of footpath away, enough of metal roofing to load 400 men. I was not allowed to hire them myself. They had to be asked from the Administrator. He sent to certain chiefs, who sent men to me, and I sent them to Lusambo. I provided them with money to buy food, and paid them for their work when they returned. Some went willingly, others were obliged to go, whether they liked it or not. I was especially unhappy about it because some of the men became ill on the way. One died en route, another returned with smallpox. The whole business was most distressing. I told my fellow missionaries that I could not return to Congo after furlough if I must use forced labor. I was willing to return to preach the Gospel, but not to employ workmen unless employment was one hundred per cent voluntary. While sometimes for certain reasons obligatory recruiting was necessary for other enterprises, in general the Mission has had all the help it needed on a voluntary basis.

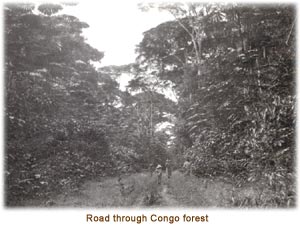

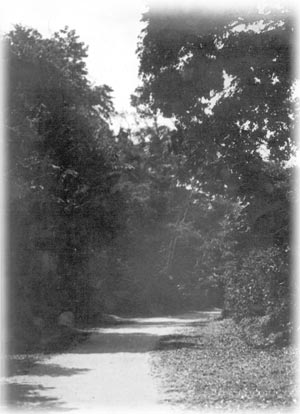

But the foregoing experience forced me to think deeply on the subject of transportation. Roads were being built. However, I knew that the Mission could not afford to use trucks for our transport. With American chauffeurs, I was told, the lifetime of a Model T Ford truck was figured at 8 months. We could not afford trucks at that rate. On the other hand we could not afford missionary time for truck driving. I wondered how our problem could be solved.

One of the marks of the backwardness of Central Africa before the coming of the white man was that, so far as is known, the people had never learned to use the wheel as an implement for their work. Not even a wheelbarrow was in use among them. And they had no beasts of burden, neither horse, mule, donkey, ox nor camel. When I saw porters returning from a journey with heavy loads, on shoulders sometimes raw, I lay awake at night and worried over the problem.

These loads must be taken off men's shoulders and put on wheels. But how? I designed a two-wheel cart for experimental work by removing and using the wheels of my motorcycle. The cart worked, but was too light to stand the shocks which careless men would be sure to give it. Some of the missionaries helped out with the money to buy a front axle and pair of wheels of a Model T Ford car. By using triangular bracing to lock these wheels in position, it was possible to build a substantial cart. Because the hills were steep and dangerous we needed a strong brake. My design of a very crude brake was not much for looks. But with it one man behind the cart could lift the loaded cart off the ground. This brake served as a drag on the ground, and served us until Mr. Wharton invented a better one.

A friend of ours, an American mining engineer, to whom I had gone for information about needed Ford parts, told me the cart would not work. He said the natives simply did not have sense enough to operate a cart. The diamond mines had tried one, and found their men unloaded it and carried both the cart and the load over a hill. But we knew better. Our experiment worked, and while it took a great load off the shoulders of the porters, it also took a great load off my mind.

After the cart had made a successful trip to Luebo, 325 miles away, with four cartmen hauling as much as eight porters would have carried, the men came asking for increased allowance for buying food for the next trip. I told them I was going to pay them by the pound, then they could spend as much of their money for food as they wished. The bigger the load the more money they would receive. They said they didn't want that. They wanted a monthly salary, and increased food allowances. I answered that I would pay only by the pound. A strange misunderstanding put the idea across with a bang. Mr. John Morrison, formerly with the SEDEC at Lusambo, had now come to Luebo as associate Mission Treasurer. From long experience he thought in kilograms, while I thought in pounds. Sending four men with the cart, I asked for a load of 400 pounds. I had set a pound rate which would give the men a little more per pound than our previous costs. If they worked well they could increase their earnings. Mr. Morrison read 400 pounds, but he was thinking 400 kilograms, which is 880 pounds, so that is what he gave them. These men came back to Bibanga after a month's absence, and were they angry? It looked as if our transport project was shot. Then I figured their earnings for the trip, and the men were amazed at what they earned. By arranging it so that a man could go on a trip for a month, and stay at home for a month, we soon had all the cartmen we could use. For years this system of transport was used on our stations. The only thing needed to make it work was one change from pounds to kilos, dramatically to prove its advantages to the workmen.

When we built the cart, only dugout canoes were available for crossing the Lubilashi and other rivers. But when ferries were put there for automobiles, I designed a wagon, using Ford front wheels and axles both front and rear. The wheels at the rear were rigidly fixed, while the front wheels turned for guiding the wagon. The man running in front did nothing but lead the wagon. Men at back and sides furnished motive power. As the men's principal food was manioc, these wagons could well have been called manioc motors. When this type of wagon was widely used it gave much satisfaction to those of us who sponsored it.

It should be remembered that my primary object in going to Africa was to preach the good news of salvation through a crucified Saviour. Though other necessary activities consumed much of my time, they were secondary in importance. Throughout the years I preached as much as I could. In fact the preaching on Sundays was a tonic in my life, and without the recreation of preaching Christ I could never have stayed in Africa. The years at Bibanga gave Sundays free for preaching, and as far as possible I visited a number of villages each Sunday on the motorcycle.

Though it was hard to get away from my many employees on weekdays, I did manage at least three itineration trips during the three years, two of them accompanied by our family.

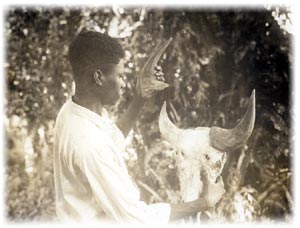

When I was leaving on an itineration without the family, Frank McElroy suggested that I stop at the river crossing to shoot a hippopotamus, sending the meat back home for use in a conference of evangelists. I agreed to try. At the crossing we asked the boatmen whether there were any hippos around. They told us to listen. We could hear the hippos bellowing beyond the bend of the river. So we left the loads and the motorcycle at the crossing, rented canoes, and started up river. As we rounded the bend we could see a number of hippos, as many as seven or eight at a time, swimming in the river, spouting and playing around. I told the boatmen to put me ashore at a place where the dried clay showed the footprints of many hippos. Sitting down on the dry clay I ate lunch and planned strategy. My rifle was too light for hippos. As the hippos were all playing on the other side of the river I decided to get nearer to them. We paddled up river, left the canoes, and walked down the far bank behind the hippos. Look! When we got there the only hippos in sight were right over there where I had eaten lunch. They were playing hide and seek with me. It seemed best to go back to the canoes and float down the river, thus being within shooting range of any hippo I might see. A hippo came up, I fired at him, and registered a hit. He went under, but as we floated along showed up, so I shot him again. Suddenly we had a scare, for a half-grown hippo bobbed up close to our canoes. The men were frightened, and lay down in the canoes. The hippo was scared too, and ducked under the water. Then the men began to laugh at the frightened hippo. Really, it was no laughing matter. We were in danger. Anyone of dozens of hippos might come under us and dump us in the deep river, and kill us with their tusks, or watch us drown. However, we kept floating down river, and the wounded hippo did the same. I shot whenever I saw him. Arriving at the crossing the men were all for continuing the chase. As sunset was approaching and a motorcycle could not travel those crooked paths in the dark, we were obliged to leave our hippo. It was reported that villagers twelve miles farther down feasted on him a few days later. Reluctantly the porters went with me, mourning for hundreds of pounds of good meat floating down river.

One subject of discussion among missionaries had always puzzled me. It was the question about a man marrying his deceased brother's wife. Sometimes this amounted to marrying the widow as if she were a slave, without her consent. Because it was commonly practiced in some tribes, the subject kept coming up again and again. But an inheritance that was even worse, and never debatable, was the case of a man marrying his father's widow. Why he would want to do that I could not see. But imagine my thoughts when on itineration I happened upon this case of a candidate for baptism. Up to this point his answers had been satisfactory. Then I asked him, "Are you married?" He said he was. I asked, "Do you have any children?" His reply was peculiar, "She has two children." I was a little irked at the seeming evasion. I asked then, "Have you any children?" He answered, "I have one child." So I inquired, "Whose is the other child?" He said, "It is the child of my grandfather. She was formerly my grandfather's wife." If you can figure out all the several relationships of those two children, you must be adept in such matters.

For building purposes I was rather partial to the four or five months of dry season. Rains can greatly hinder the making and drying of bricks, and all masonry construction, especially when mud is employed for mortar, as was then common practice. We were surprised in the middle of a rainy season, when an unseasonable dry spell was threatening future famine, to be told that out in the heathen villages people said that Kabemba (that was I) was holding up the rain, to facilitate his building program. Of course I wouldn't have done that even if I could. I was worried that people should believe such a thing. Next day was Sunday. I was in charge of the afternoon Sunday School.

There I called on two of the elders to pray for rain. Within 24 hours it poured. Just what the heathen said then I do not know.

Some time later Mignon was seriously ill. Dr. Kellersberger was on furlough, so Dr. King of Mutoto station, about 120 miles away, was supposed to care for us. He came, and took charge of the case right through, even though there was illness in his own home.

Wife's condition was extremely serious. Our baby Roberta was born, and it seemed as if there was no hope of saving the life of either mother or daughter. As I knelt by Mignon's bedside, thinking she was gone, I felt absolutely desolate. To be left at a little station in Central Africa, ten thousand miles from home, a bereaved husband with three small daughters, was a darkness that could indeed be felt. Through many long hours while her life lay in the balance, Dr. King devotedly did everything that could be done to save her life. Slowly she began to get back a little strength. Miss Farmer, our nurse, and Mrs. McKee did all they could in the way of nursing. But part of the night nursing necessarily fell to me. The next six weeks were hard weeks. It was rainy season. I had unroofed a brick house to replace the grass roof with a metal one. Not covered, the mud-mortar walls would soon wash away. I had to work very hard during the day, and help nurse wife and baby at night. At the end of six weeks it seemed as if the worst was over. Baby was gaining, and Mignon was able to walk again. But one nightI was so fatigued that I forgot to set the alarm clock for the baby's two o'clock feeding. We have always been so thankful to God that we waked up at two o'clock without the alarm. While Mignon was making little Roberta comfortable, and I was preparing her bottle, Mignon called me to say that the baby was gone. She was alive when we waked, and died while her mother was caring for her. Oh, how we did thank the Lord that we were spared from sleeping through that hour!

For a very special reason we buried baby Roberta in a neat native-made basket. It was a question of con- science. Before foreigners came the natives of most tribes buried their dead in mats woven of reeds. After the people saw missionaries and their children buried in wooden coffins covered with cloth, they wished to imitate the foreign method of burial. But they lacked the boards, and often the cloth too. At Luebo this had become a problem. Our sawmill production was needed for so many other purposes that we could not afford to build up an ever growing business as unpaid undertakers. I had helped to make coffins for two Christian leaders there. But when relatives kept coming with requests for coffins to bury all who died in a village of ten thousand souls it was quite another matter. I suggested that they could continue to bury as they had always done, or if they really wanted wooden coffins individuals could saw lumber as it was done elsewhere, and sell it to the public. I did sympathize with them. I told Mignon that when I died I wished to be buried in mats after the native custom, just to show that there was no special value in wooden coffins. We had not forgotten this when little Roberta died. We decided to bury her in a native-made basket, in a grave lined with native mats. This helped us with good conscience to say no to the frequent requests for boxes for the burial of their dead.

One morning at breakfast we were all excited by a message saying that there was a buffalo on the station. So we got our guns and went after it. It was killed. I knew that I had not done the killing, for the shells of the ancient Martini-Henri rifle I used never went off.

One evening I happened to be on the front porch of our house, overlooking the beautiful Lubilashi valley far below. Something new appeared, and I could hardly believe my eyes. There in the distance was a rainbow by moonlight. Hurriedly I called Mignon to see it, for I feared folks would think I dreamed. Then I looked up the subject of rainbows in an old encyclopedia, and found them described as phenomena appearing by sunlight or moonlight.

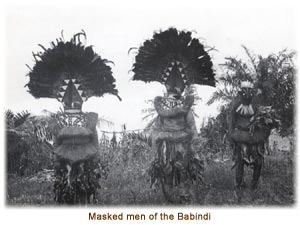

We were traveling among a depraved people. Their customs were of the vilest. Examination of candidates for baptism, and of Church members before communion, in some cases brought out facts which were altogether sickening.

One of the customs I remember was that young boys and girls were paired off in childhood by their parents as "friends." This was not even a pretense of marriage, nor trial marriage. These children lived together in sexual union. When they grew up, the girl was married off to another man, the boy took another woman as his wife. They might go to live far apart in distant villages. But when there was a funeral in the old home town, they returned for the days or weeks of wailing. For the duration of the long funeral these "friends" of childhood lived together again in sexual union. Afterward they returned to their regular marriage partners. Thinking of such things in connection with the breakdown of sex standards in America, one marvels at the patience of Almighty God. Why should He let our nation survive until we all reach the level of the Babindi?

Work among these people was so difficult that none of our evangelists wished to live among them, nor rear their own children there. Many years later some of those evangelists still looked back with horror to the days when they were assigned to serve there.

When they wished to describe a section as of the very lowest, they likened it to the Babindi country.

That Babindi country is just about as hilly as any country could be, for most of the path was uphill, which was bad, and the rest of it was downhill, which was worse. Our family was supposed to be traveling by hammock. But the paths were so much uphill and downhill that we really traveled on our own shoeleather much of the time. In fact, two feet were sometimes not sufficient for the steep climbing. Occasionally we had to use both hands and both feet for getting over the steepest places.

If you have ever traveled six hours per day for three weeks, and slept in a new place every night, you may understand this itineration by our family. In 21 days we lived in 18 huts, moving every day except Sundays.

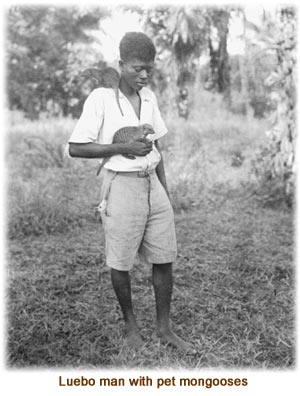

Probably you have never broken up housekeeping eighteen times in three weeks. Early every morning we rose for a new journey. The cook and houseboy prepared breakfast while we had our private devotions. Then while we ate breakfast, cots and mosquito nets and sheets and blankets were quickly packed up. Pots, pans, and dishes were washed. Then the table and chairs and boxes were gotten in readiness. The porters bustled about getting their loads. The boxmen and hammockmen were all gathered at roll call. A hymn was sung and prayer offered. Then through the long wet grass of the early morning, or through forest paths, the long caravan started off for the next village where the Mission had a teacher-evangelist.

About noon or later the village might be reached. There was a rush of preparation. Our dinner must be prepared and served. Beds had to be set up, mosquito nets hung, table and chairs made ready, water for cooking and drinking boiled to kill the abundant germs, and everything put in order for the afternoon and night. This of course was not done without observation. A crowd flocked around mentally photographing every object we had and every move we made. Obviously the observers could not be permitted inside the hut where we stayed. But they came as far as the sentry would permit, and sometimes farther.

Mignon was free to meet groups of women, and to get acquainted with the wives of the preachers, work she dearly loved. She also had to keep an eye on our little girls, as there are all kinds of health hazards in ordinary village life, flies, jiggers, and parasites. She was specially interested in getting girls and women to see that school and books were meant for them as well as for the boys and men. In some places parents did not want their girls to attend school, as they were needed to work at home or in the gardens, or babysit while their mothers worked. Mignon also liked to teach them to sing.

The Congolese children memorized readily. All who professed faith in Jesus were expected to learn a Tshiluba language catechism. This was a basis for explanation of the things of Christ. Some of these catechumens were ready for examination, to see whether they were sound in their faith, and faithful in their living. Such as were found ready would be baptized at the preaching service, which was usually held in the afternoon.

Following the preaching service individual members of the Church would appear before the elder and missionary and evangelist for questioning before coming to the Lord's table. Were they really living for Christ? Usually some would be found faithful, but some would have backslidden. Sometimes the sin was polygamy, other times stealing, drunkenness, adultery, the worship of spirits, or other sins. While the outward symptoms differ, sin is essentially the same through the ages, being "any want of conformity unto, or transgression of the law of God." Often the sinners were penitent, sometimes they were not. They were dealt with according to their attitudes; sometimes temporarily suspended from communion, or where they were altogether hardened in sin they were excommunicated. Then there was the examination of those previously disciplined, and restoration to Church fellowship of those who seemed to be really penitent. I

One of the most hopeful aspects of our work has always been that many of those who have gone astray have come back in true repentance to their Saviour.

Whenever there were communicants the Lord's Supper was observed, at night. At the Lord's table would be gathered a little company of those saved out of the night of heathenism by the bright shining of Jesus, the Light of the World. What these people had been saved from I had opportunity to observe in the examination of catechumens. Often tears came to my eyes at the communion service as I thought of the dark past and the glorious future of these fellow Christians gathered around the simple table with the elements representing His body broken for us, and the blood of the new covenant, shed for the forgiveness of sins. And in my heart I was glad I was a missionary.

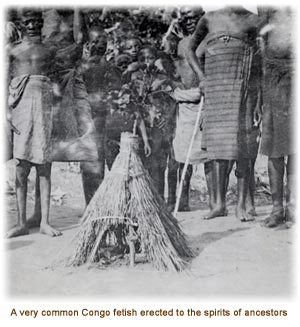

One day our party reached Mukumbule, one of the many places "where every prospect pleases, and only man is vile." The village was built in a magnificent grove of palms. The huts were not much to boast of -Congo huts, having thatched roofs, are usually in a state of decay. While the huts were second-rate, and even poor, the village had an unusually large number of fetishes, in a country where fetishes are common. Through the long, winding village street, one could never get out of sight of one or another of the big ones. Each was made of a conical mound of earth, flattened on the top, with a lot of bushes stuck in the middle, and the whole mound gaily decorated in bright colors. These mounds were neatly made, and were given the places of prominence in the street. Throughout the village there were also large numbers of a different kind of fetish -bottles brightly decorated with colors, with feathers in the corks and who-knows-what on the inside. Most of the houses would have at least one of these bottles near the door. Some huts had as many as four or six.

Having arrived in the village somewhat after noon, I preached as was my custom. But there were no candidates for baptism. In the evening there was a communion service. Few from Mukumbule took part. Most of the communicants came from other villages. The outlook was not bright.

Two villages were to be visited next day, so I retired soon after the communion service. Early next morning the party arose, had breakfast, and packed up for the journey.

Mignon and the little girls had gone ahead in their hammocks. The boxmen had hurried off with their loads. My own men stood ready with the hammock, wishing to get into the path before the sun became too hot. After completing such arrangements as had to be made. I was just about to get into my hammock, when the pastor and elder who traveled with me came, looking troubled.

(My friend the anthropologist says that witch doctor is not the correct name. But it will convey the idea better than some other term, so I let it stand. On this trip among the Babindi I had my only important experience with a witch doctor.)

"We have a matter to talk over with you before you leave here," said the elder. So I turned back for a conference before leaving Mukumbule.

"We sat up late last night considering the state of the Lord's work in this village," said the pastor, "and we find it to be very serious."

"What seems to be the trouble?"

"There is a witch doctor here who is hindering the work with every means at his command. If he merely followed his own business that would be bad enough. You can see all the fetishes he sells to these poor people at scandalous prices, thus keeping them wretchedly poor. Besides that he deliberately interferes with those who wish to worship God here. He intimidates them with threats."

"Tell me more about him."

"He lives in this village. He made all the fetishes you saw, the big ones at every turning of the village street, and all the small ones you saw at the doors of the people's huts, those bottles. For all of these they paid him big sums of money."

"Is that all he does?"

"Oh, no! He makes charms to put on people's necks. He claims that he can make it rain when he wants to, and can prevent it from raining. He says he can make sick people well and well people sick. He says he can make charms that will cause people to die."

"But how does he interfere with our work here?"

"That is what we wanted to talk about. You know that the Government promises us religious liberty. But this man tells the people that he has investigated the white man's God, and found him to be of no account. They need not worry about that God. However, he says that if they do not obey him, the witch doctor, he will make them suffer for it. He says the people must not send their children to school or Church or catechism class at such times as he forbids it. If they send them at such times and it breaks his charms, he will beat the children, and what he will do to the parents will be enough."

"Do the children really mind him?"

"Truly, they are very much afraid of him, and that is what makes the situation so very bad. Because of that one man's threats the work of the Lord in this village is almost dead."

"What do you want me to do about it?"

"We want you to write a letter to the Bula Matadi (name for a state officer or for the Government) at Panyi Mutombo, asking him to order the witch doctor to stop interfering with the work of the Gospel."

"Do you think that would cure the trouble?"

"Oh, yes, the Bula Matadi could stop the whole thing." "But it seems to me there is a difficulty in the way. Suppose I do send a note to Bula Matadi, what will happen then? He will call for witnesses. Then if our evangelist goes to tell what he did, the witch doctor will threaten and frighten a hundred people into going as his witnesses to say the charges are not true. What can Bula Matadi do but decide in favor of so many witnesses? Then you will return, and the people will laugh at the evangelist and the Gospel, and even at God Himself."

"What then can be done?" I sent a man to call the witch doctor, another to call the head man of the village, and a third to bring his Tshiluba Bible. I opened the Bible to Acts 13.6-12.

The witch doctor came, rubbing his eyes, for he had just gotten out of bed. The head men of the village also arrived. First I turned to the head men.

"You people in this village are very foolish. You have in the village this witch doctor, and poor as you are you pay him large sums of money for making his medicines, and they can do you no good at all. This man has no power. He can do none of those things he claims to have power to do. Yet you fear him and waste your good money by paying him for these worthless fetishes."

Then I took the open Bible, and turning to the witch doctor I explained to him some of the background of Acts 13, then began reading at verse 6, in Tshiluba (herewith I quote the English version) :

"And when they had gone through the isle unto Paphos, they found a certain sorcerer, a false prophet, a Jew, whose name was Bar-Jesus: Which was with the deputy of the country, Sergius Paulus, a prudent man; who called for Barnabas and Saul, and desired to hear the Word of God. But Elymas the sorcerer (for so is his name by interpretation) withstood them, seeking to turn away the deputy from the faith. Then Saul, who is also called Paul,) filled with the Holy Ghost, set his eyes on him, and said, O full of an subtilty and all mischief, thou child of the devil, thou enemy of all righteousness, wilt thou not cease to pervert the right ways of the Lord? And now behold, the hand of the Lord is upon thee, and thou shalt be blind, not seeing the sun for a season. And immediately there fell on him a mist and a darkness; and he went about seeking some to lead him by the hand. Then the deputy, when he saw what was done, believed, being astonished at the doctrine of the Lord."

Then I continued to speak to our witch doctor: "Now you have heard what happened long ago to Elymas the sorcerer. I am here to tell you that you are just the kind of person Elymas was. You are a child of the devil, an enemy of all righteousness, and you pervert the right ways of the Lord. You have withstood the work of the Lord just as Elymas did when he tried to turn the deputy away from the faith. You have blasphemed the name of God by saying the people need not fear Him."

"Chief, I never did those things. I never blasphemed God's name. I never interfered with the worship. I have done none of those things."

"Now, see here! You cannot deceive me, and you cannot deceive these people. All the people of the village know what you have done and said. Hush! do not add any more lies. You are a wicked man. And now, to show these people that you have no power, and that you cannot do what you claim, I challenge you to kill me with your charms during the next thirty days. You say you can make charms that will cause people to die. Very well, make all the charms you like for the next thirty days and see whether they will kill me."

"No, no, Chief, I do not want to kill you."

"But you couldn't if you did want to."

I continued, "On the other hand, you have told the people they need not fear the God of the missionaries. You said He has no power. The God of the missionaries is the Creator of heaven and earth, Nvidi Mukulu. He is the one who created all men. He created you and me. A long time ago He sent this man Paul, of whom I have just read, to preach His Gospel. Now He has sent me to preach the same good news. Elymas the sorcerer withstood Paul. God laid His hand on Elymas and he became blind. Now you have withstood the Gospel here. Right now this little group of Christians can pray to God to lay His hand on you. We can pray to Him right now, and then we shall see how long it takes Him to lay His hand on you and make you blind."

The witch doctor was scared. "Oh, Chief, don't do it. They have told you lies. I never did those things they . . . . . . . ."

"Hush! hush! Do not add any more lies. You know and these people know that you have talked against God, and said He has no power. Now let us try Him and see whether He has any power."

"No! No! Chief, do not do that." After the witch doctor had begged sufficiently to show the village chiefs and all the people just how much he feared the God against whom he had spoken so bravely, I turned to them and said, "Now you can see what kind of man this witch doctor really is. I am not afraid of his medicine, but he is afraid of this God whom he has been talking against."

Turning to the witch doctor, I said, "We shall not do this thing at present. We will not pray God to hurt you. We are your friends, not your enemies. We have come to help you, not to hurt you. I hope you will truly turn to Christ, and preach His Gospel instead of withstanding it."

Shaking hands with the witch doctor, I said, "Now goodbye. I shall be praying for you to be converted. But I warn you in any case to stop interfering with the work of the Lord. Wherever I may be, whether off in other villages on this journey, or yonder at Bibanga, or far away on the great waters, or even in the distant foreign country, the word can reach me. If word comes that you have resumed your evil ways of threatening people who wish to worship God, at that time we will have a prayer meeting and ask God to lay His hand on you as He did on Elymas the sorcerer long ago. Then we shall see how long it takes Him to answer prayer. Then we shall see whether He is a God to be feared or not."

Bidding goodbye to the headmen of the village, I got into my hammock, and the strong hammockmen hurried off with me in pursuit of the rest of our party.

Later I heard that after our departure the witch doctor stepped up to the chief of the village and said, "You went and told the white man tales about me."

"No," said the chief, "I did not tell him anything about you." "I told the white man about you," said the evangelist. "What do you have to say about it? Do you want me to call the white man back?"

Three months later it was reported that the witch doctor had lost all his influence in the village of Mukumbule, as people no longer feared him.

By the end of our first term in Congo two ideas were fixed in my mind. One was that there ought to be a cotton mill to produce cloth for the native people at a reasonable price. That first idea was voted down by the Mission after I had investigated the matter, because of the high initial cost.

The second idea was that we ought to publish a monthly periodical in the Tshiluba language to provide mental and spiritual food for the teachers we had placed in hundreds of villages, as well as for the pupils in our schools. This was no new idea. There had been some sort of periodical before the First World War. It was a casualty of that terrible conflict. I felt so strongly that there should be a regular monthly Church paper that I continued to agitate for it through our second term. The Mission agreed that the objective was desirable, but saw no way to accomplish it. When I secured a mimeograph, Mr. V. A. Anderson and I were made editors. We published a little paper every three months, calling it the LUMU LUA BENA KASAI, that is, News of the People of the Kasai. While we were busy with other assignments, we were planning how we might bring messages of cheer and hope to lonely workers in heathen villages. Every year at Mission Meeting I would urge that the paper be printed every month at the Mission Press at Luebo. By and by the Mission agreed to print it at the Mission Press every three months.

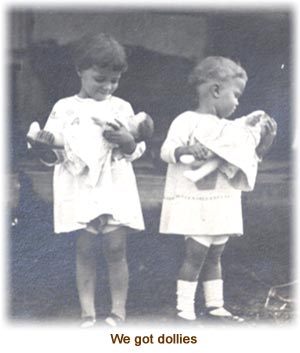

Bibanga station got its foreign mail by foot messenger from the post office at Kabinda, fifty miles to the east. Our little girls received from America a gift of two crying dolls. They came by mail. It was a much puzzled messenger who arrived at Bibanga after traveling two days with that mail sack on his head or shoulder. All along the way he heard the funniest noises coming out of the mail bag.

The life of children on a Mission station often takes on some local color. After Dr. Kellersberger returned from furlough there was constant talk of operations being performed at the hospital. Frank was the surgeon, and the girls were nurses. The patient was one of the crying dolls. The surgeon cut out the part that cried.

Africans and foreigners often failed to understand each other. An Administrator of our Territory once had instructions to erect some rain gauges for scientific purposes. He fastened one to a post near the house of a chief, leaving orders that it must not be touched. When he returned to the village after some time to check the rainfall he found his gauge perfectly safe. The chief had had his workmen build a roof over the gauge to protect it!