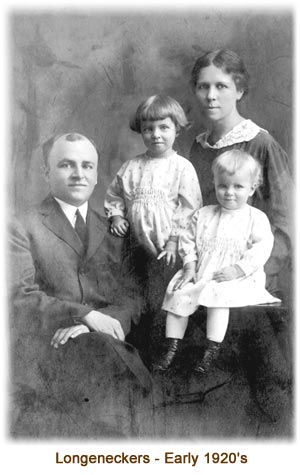

Returning to Congo after our first furlough, we landed at Matadi. Our two little girls, Alice and Dorothy, did return with us. We spent a day or two with Dr. and Mrs. Joseph Clark at the American Baptist Mission. Dr. Clark knew lots of good Congo stories. He had a beard. After sitting on his knee little Alice came to whisper, "That man has fur on his face."

Our travel agent told us we were booked for Monday's train, to Kinshasa. I told him we wished to go Friday. He said there was some technicality about the tickets, and the change could not be arranged. However, by means of quiet insistence I got the booking changed, and we did leave on Friday's train. We arrived at Kinshasa Saturday instead of the following Tuesday. Mr. Cleveland, our Mission Treasurer at the time, had come down river with our Mission steamer Lapsley, to make the arrangements to put her in dry dock for repairs. He had expected to sail with us on the steamer Aruwimi. When he heard that we would arrive Saturday instead of Tuesday, he changed our bookings to the Reine Elizabeth, which was to sail some days earlier. Just why I felt so positive we must leave Matadi on the Friday train was not clear to me at the time. We might have had a very happy weekend with the Clarks. But the reason was clear enough some months later, when we learned that the steamer Aruwimi on that particular voyage up river, was bummed up with the loss of a number of lives. She had a cargo of gasoline. If we had sailed on her this is probably what would have happened: At the Basongo landing we three men would almost certainly have gone ashore for a walk. Mignon and the children, with Mrs. Allen, would just as certainly have stayed on board ship, and would probably have been burned to death. To us such things do not happen by chance. We believe definitely in the guidance of the Holy Spirit, and we are confident that it was He who led me to get a change of bookings at Matadi, without my knowing just why.

Our trip up river on the Reine Elizabeth was not specially noteworthy, except that we had quite a bit of fun. Mr. Cleveland and the AlIens were good company. On April 1 we played some jokes on each other. Mr. Cleveland came and asked me whether I wanted the native passengers to play with my new motorcycle on the lower deck. Naturally I rushed downstairs, only to be told it was the first of April. The rest of us sent Mr. Cleveland a letter which contained only blank paper.

The Reine Elizabeth did not have enough cabins for all the passengers. A few of us had to sleep on camp cots on the deck. My own cot was set up near the family's cabin, under a large water pipe which curved over it like the handle of an umbrella. Next morning I jumped out of bed in shocked surprise when a stream of cold water hit me right in the middle. Crewmen had turned on water for washing the decks, and someone had left this faucet open. In those days there were few white children in Congo, so most ships were not safeguarded as they are now. Two cables stretched around the upper decks were the only guard rails, so small children had plenty of chances to fall overboard. Two open stairways also were dangerous. In addition to these two serious hazards, the rudder chains passed along the decks, and where they passed over rollers little hands or feet could very easily be caught and crushed. One day baby Dot stood looking at the cables at deck's edge, and said, "NO!" Next she faced to two stairways and said, "NO!" Then she went and paid her respects to the steering chains and said,

"NO!" She had grown weary of hearing that word every time she turned around.

Their aunt Catherine had given the children a brightly colored rubber ball about a foot in diameter. They loved it. It was a sad day when it rolled along the upper deck, bounced down the stairs and off the lower deck into the river. We could see the beautiful thing floating, mostly above water, as we left it farther and farther behind, a pretty plaything for crocodiles and hippos.

At Luebo we learned that our family had been assigned to Bibanga station, which was 325 miles of native footpaths southeast from Luebo. I had a motorcycle, a light one. But Mignon and the little girls had to travel by hammock. We had a two weeks journey before us. After things were packed each morning and the caravan started, I could pass them and go ahead to the next village where we were to spend the night, and get things ready for their coming. A guest house could be cleaned and swept 1 and the dust settled before the porters arrived with cooking utensils, table and beds. We could also make sure of food for our porters, and better arrangements all around than if we had all arrived together. However it was a long, tiresome trip. Those who travel in Congo nowadays can hardly realize what it meant then to travel over the long, hot miles. Often high grass and weeds scratched one's cheeks. The sun beat down from the sky. The hammock men sang more and more lustily as they grew more and more tired. "Dumba Tuya, Dumba Tuya, Dumba Tay, Dumba Tay," these and other nonsense rhymes were sung mile after mile, until they became wearisome to the passengers. But the villagers in every village were glad to see us. The coming of a white man was still a great event. But the coming of a white lady, with white children, that was something to be remembered and talked of around the evening fires for a long, long time. The motorcycle was not less notable. At that time there were very few motorcycles in Congo. So the people crowded around in wide-eyed astonishment at one more marvel produced by the white man in his foreign country. They could not realize what such things cost in the way of ingenuity and hard labor and teamwork. Of cloth and many other things we had, it was said that white men brought these things up out of the ocean. I could hear them discussing the motorcycle. Someone pointed out that the tires were just like a snake. It was fun showing off my new toy to the people. In one village a great crowd gathered to watch me. I had a powerful klaxon on the motorcycle, so waited until all was comparatively quiet, then suddenly sounded off. The crowd backed away so quickly that the mass of the people on one side broke the roof of a hut as they backed up against it. After that motorcycle was worn out I put the same klaxon on a bicycle. One of the missionaries said I jacked up the klaxon and put a bicycle under it. Anyway it was a strong voice for a bicycle. Many times I honked behind a line of natives in a narrow footpath and they jumped aside, and then burst into shouts of laughter, or at least broad grins, as they saw it was only a bicycle.)

One of the problems of the long journey was food for the necessarily large caravan. It takes all the joy out of life to arrive in a village, eat your own food, then feel that your men who have borne the burden and heat of the day must go to bed hungry. So goodbye hammock travel. I shall never mourn your going!

On this motorcycle trip to Bibanga I had the curious experience of being lost in the middle of a great grassy plain in broad daylight. So long as there is only one path one can only go forward. But where six paths converge and there is no signpost one can be seriously puzzled. I came to such a point when alone on my motorcycle far ahead of the caravan. Some distance away I saw a few people. Unfortunately they were scared by the funny machine that said "tuka-tuka-tuka-tuka" all the time. The more I called them the faster they ran. They ran through the grass, not on the paths where I might have overtaken them. Soon I was all alone with the sun overhead and a half dozen paths at my feet. Praying for guidance I took what seemed to be the right path. By and by I reached the distant village. This plain was uninhabited for many miles in every direction, for the lake in the middle of it was supposed to be the dwelling place of spirits, and people were afraid to live there. (Years later our missionaries began going to this beautiful Lake Munkamba for vacations, and later numbers of white men and Congolese had homes on its delightful shores. It has no crocodiles or hippos. It is fine for swimming.)

High on the hills to the east of the Lubilashi River one can see Bibanga station long before he reaches it, as I learned to the amusement of my hammockmen on my first visit. We were most heartily welcomed to the station by the McKees and the McElroys and Miss Rogers.

My assignment from the Mission was to build a hospital for the work of Dr. E. R. Kellersberger (who served on our Mission for 24 years, then became Secretary of the American Leprosy Missions). He had served one term with pitifully inadequate equipment. So I was sent to build a hospital for him. Dr. Kellersberger is now deservedly famous. I recall that we once had a visit by the Commissaire de District. Dr. Kellersberger was showing him the spots on a leper's back, insensitive to the prick of a pin. The official drew back in horror, saying, "Doctor, do you touch them?"

The missionaries showed me where the new hospital was to be built. It was on a gentle slope draining away from the station. The foreign material resources were pointed out: A rough shed contained metal roofing, nails, tiles for the operating room, a hand-operated brick press, a limited quantity of cement, tools for masons and carpenters, and some pitsaws and crosscut saws. It was explained that there had been some carpenters, masons, and pit sawyers. But most of these had gotten jobs at the diamond and copper mines, or elsewhere. The lumber for the doors, windows, ceiling and roof framing was still in trees scattered around the landscape. The bricks were still to be made. Was there good brick clay? No, not very good. It was hoped I could make the bricks out of two or three gigantic termite hills down in the valley some distance away. The wood for burning the brick was still in the scrub trees scattered around the hills. There was no vehicle for transporting anything. All transport had to be done on human shoulders. There were two good masons to help me. It was necessary to train crews of carpenters, masons, brick-makers, firewood cutters, and sawyers. The work at the Industrial School had given me good experience in organizing workmen to get things done. I had learned from Dr. Morrison one little secret which helped me a great deal, in employing African labor. He said, "If I were to send two men to cut grass, I would make one of them kapita (foreman) over the other." Unless there is someone on whom to fix responsibility things will not go right. So through a system of responsible kapitas the work began to progress. Just as largely as possible a quota system was used, for the individual or for the group. Giving each man a task for the day always gave us the best results.

(Nyoka means snake.) Much firewood had to be cut for brickburning, and had to be carried quite a distance. Wood was not plentiful in the high grass country around Bibanga; firewood was scarce. However there were scrub trees scattered in the grass, and these would do for brickburning. Our firewood kapita was named Nyoka. He was well named, for I soon found that he was a crook. He somehow coerced his men into working his little farm, somewhere down a valley, in addition to their other work, or in place of it. When Nyoka learned that I had found out the facts about him he suddenly took his departure and I have not seen him since.

Mention might be made of an itineration among the Bena Kalambai. I wanted to see the chief of the village where I was to spend the night. He was reported absent. Questions brought out the facts. The old chief who was overlord of many villages kept this village chief in constant fear. Repeatedly and inexcusably he imprisoned this sub-chief, and by cruelty forced the sub-chief to pay him goats and chickens, or more women to add to his large harem. People living in a free country can hardly imagine the forms of extortion invented by hard-hearted, greedy chiefs. I am not an advocate of colonialism, as developed through the centuries, for it was motivated too largely by self-interest. But something could be said for colonial administration if it were solidIy built on the motto of one Governor-General: "Dominer a servir," that is, Govern in order to serve.

The missionary interest is not in governing the people, but in the salvation of their souls. Even if the people had had a perfect animal happiness, still we must take them the Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ to satisfy the need of their souls. For the eternal, loving God who created all men, has not created Africans to live and die like beasts. Jesus sent us with His good tidings to all men unto the uttermost parts of the earth.

One time a hut was needed as a lodging for somebody. I had no time to look after building it. So I picked a man from the workline, and said, "You are the kapita. I want you to gather the materials and build a hut at such and such a place. Pick out five men. You are the boss. Go build the hut." By and by he returned and told me the men refused to work for him. He explained, "They tell me, 'You are only a black man like we are. We will not work for you. We came here to work for a white man.'"

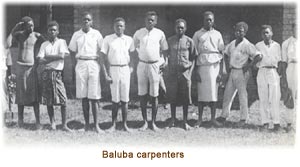

Most of the men were so ignorant of ordinary mechanical ideas that they had to learn everything from scratch. Even a simple door knob was too much for them. It was amusing to see a raw fellow from the hills go after a job like turning the crank on a drill press. He did not understand the principle, therefore he fought the handle when it turned to come back at him. The untrained native has no idea of a right angle. So while many of their huts are four sided, they are hardly ever rectangular unless the builders have had some training. Native villages were rarely laid out in squares. The houses stood higgledy-piggledy, rarely, if ever, in line. Therefore getting skilled masons, carpenters, cabinetmakers and sawyers, meant training men from the ground up. They had plenty of native talent, but it had to be educated in the skills we required. Here my experience at the Industrial School encouraged me to go forward with what might have seemed a hopeless task. Our trouble was that other white men also needed skilled help. It was easier for them to hire my skilled men than to train their own. As they had more money than we had, it was necessary to train many more men than I was able to keep.

Again I profited from my experience by sending to the Industrial School at Luebo for a graduate to come to Bibanga to train carpenters. Misikabo and I understood each other, and he was able to teach and supervise the carpenter shop, so he saved me much valuable time.

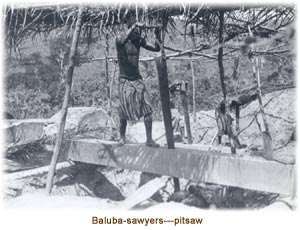

I needed lumber. It was a far cry from the steam sawmill at Luebo to cutting lumber by hand at Bibanga. I wished for a sawmill. But even if Luebo station had donated theirs to the cause, we could not have moved it 325 miles over footpaths to Bibanga. I was compelled to employ the pitsaw method which was common in many places in Congo. Trees were scarce. True, there were small clusters of forest trees down some deep valleys, but the lumber was not usable because the termites destroyed it so readily. Furniture or roof framing could soon be turned by them into empty shells that would break down. At Luebo I had gotten acquainted with nsanga trees. These trees are practically termite proof. But they are scarce. Scouting around we found there were some nsanga trees scattered over the plains. Usually the tree was found alone, or in very small groups.

But nsanga trees cannot saw themselves into boards. There were only a few sawyers left, and they had little skill or experience. I had no knowledge whatever of pitsawing. I could not be satisfied with anything less than good lumber. Sometimes on journeys I saw first-class lumber that had been sawed by hand. I reasoned that if other men could get good boards by the pitsaw method we could too. I felt blue when the sawyers brought me boards that were twisted and otherwise showed poor workmanship. These less-than-half-trained sawyers couldn't even appreciate the difference between a straight board and a crooked one. Investigation showed that in marking the long lines on the log with a snapline and charcoal dust the long lines were straight and parallel. But by carelessly marking the lines on the ends of logs they gave a twist to each finished board. A little thing like that meant nothing to primitive people, accustomed to building crooked huts with crooked trees from the forest. They thought these boards were just fine. But for me with a trade school training they were a headache.

After some time a man came to ask for a job as a pitsawyer. He claimed to understand the work. Our saws were in bad shape, so I gave him an old and apparently hopeless pitsaw to file. If he could properly file that saw it would prove beyond all doubt that he knew the trade. He turned out a fine job, and I was delighted to put him in charge of the sawing.

The men were told that instead of paying them by the month I would pay them by the board. They did not want piecework. I assured them that while one of my objectives was to increase production, another was to increase their pay. Still they didn't want piecework. But I told them it was piecework or nothing. They yielded. They were surprised to see how much more they could earn that way. But in being greedy for gain they became careless of quality, and began to bring in lumber that was poorly sawed. When I came back from a journey and checked the lumber, it was clear that an object lesson was absolutely necessary.

They were reminded that I had promised them a certain amount for each board, only on condition that it was a good board. After figuring the value of so many good boards, I counted out the metal money in stacks on the table. They saw all this money almost within their grasp. Then I explained that I simply could not pay all that good money for the poor boards they had sawed. I raked half of the money back into the cash box, and divided the rest among them. That severe lesson was effective. They recognized the justice of it. They realized that I meant what I said, and from then on I got good lumber. More than that, after they found that they were being well paid for good work, they stayed with me. I soon had enough sawyers to cut the lumber needed for our work, provided I could find enough good trees.

For those unfamiliar with the system of pitsawing it may be explained that the tree is cut down with axes, or a crosscut saw. Then logs are cut, according to the length of boards required. A pit is dug, perhaps ten feet in length, deep enough to give a man plenty of standing room while working on the under side of the log. Beams are laid across the pit, and the log rolled onto them. It is then flattened on two sides with axes or adzes, and these flat sides are lined for sawing. Then one man stands on top of the log, and his companion stands beneath it. The top man pulls the saw up, the under man pulls it down. And so they rip out the boards. It is slow work. But working in gangs they can take turns, and keep the saw going even while the men rest. Generally speaking, we were delighted with the quality and quantity of lumber they produced, and they were happy with their earnings.

Nsanga trees were few and far between. Most of those within five miles of Bibanga were soon cut down. So George McKee suggested that we mount our motorcycles and go scouting for such trees as we might find. We started eastward on the winding footpath. We had to ride slowly for fear of being thrown from the motorcycles. About six miles east George said, "Hershey, there is a lusanga tree over there in the middle of the plain. You had better get that one." I made a mental note of the location. The tree stood all alone. Seen from where we were it looked as if it might be two feet in diameter. But every lusanga tree was valuable, and we were glad to see one more.

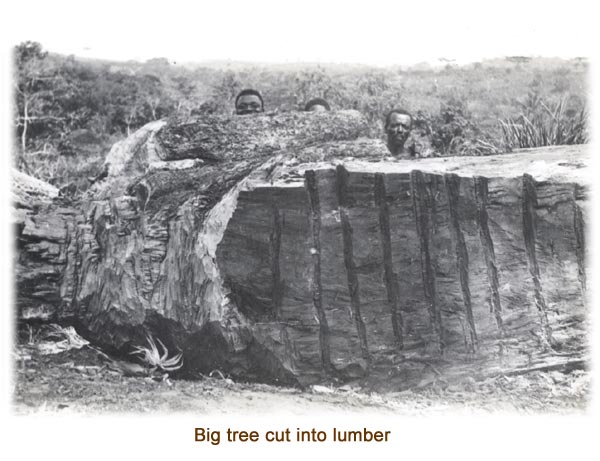

By and by I went out to examine the tree. The motorcycle had to be left in the footpath, which was quite a distance from the tree. Wading through the grass, every step increased the size of the tree. Having mistaken the distance, I had totally misjudged the size of the tree. What from a distance looked like a tree two feet in diameter, proved to be three times as large. Some simple calculations showed that it was seventy feet from the ground to the first branches. I looked and looked, for the tree seemed impossibly big, something like looking for a cow and finding an elephant. There was not only a solid diameter of six feet, but for some way from the ground upward there were heavy buttresses which supported the lone tree against storms. The section near the ground, including the buttresses, was so large that four men could just touch fingertips around it. It looked as if that tremendous tree could not possibly be cut down and turned into lumber with the tools we had at Bibanga.

By this time our lumber hunger was so great that I knew we must not pass up such a wonderful prospect of hundreds of good boards needed for Dr. Kellersberger's hospital. The Lord had prepared this magnificent tree for us, and we must, simply must, cut it into lumber. The task seemed impossible to me, but to our God all things are possible. It was decided to undertake the impossible task.

Calling the four men who usually cut down trees for the sawyers, I told them to go out to the plain some distance from Bakwa Tshinene and cut down that tree. It seemed best not to mention the difficulties involved. The men went, and being very busy with other tasks, I did not check for a few days. It was my hope that after three days they would have gotten a good start. Then it was told me that the axeman had not even laid axe to the tree. This was vexatious. A messenger was sent to warn the choppers to get busy, or there would be trouble.

The reply to that message came in unexpected fashion. Next morning the houseboy told me that four axes were lying at my door. "Four axes at the door? Whose axes are they, and what are they doing here?" I anxiously inquired.

"They are the axes of the choppers you sent to Bakwa Tshinene. They have quit work."

"Why have they quit work?" "They say they are afraid to cut down that tree. The chief of the Bakwa Tshinene village called them over to drink corn beer with him. He told them that if the white chief had sent them to cut down the tree, of course they must do it. But something dreadful was bound to happen if the tree was cut down."

You may well imagine that I was deeply troubled. It seemed there must be some native superstition about the tree. But I was deep into this problem. It was impossible to stop. The hospital needed that precious lumber. My hope lay in another gang of choppers, the men who cut firewood for brickburning. The kapita Mbelai was sent for, and the following conversation ensued:

"Muoyo, Mbelai, are you strong?"

"Yes, I am strong like a tree."

"And your men, are they strong?"

"Yes, they are strong like stones."

"Good. Mbelai, there is a big tree out at the Bakwa Tshinene. We must cut it down to get boards for the hospital. Can you and your men cut it down?"

"Certainly, Chief Kabemba, we will show you how it's done." "Very well, Mbelai, come here tomorrow morning with all your men, and I will give you salt to buy food. Then you can go and stay in the Bakwa Tshinene village until you have finished cutting down the tree."

Next morning Mbelai appeared at my door. "Well, Mbelai, where are your men?"

"They haven't come."

"Why not?"

"They're afraid."

"What are they afraid of?"

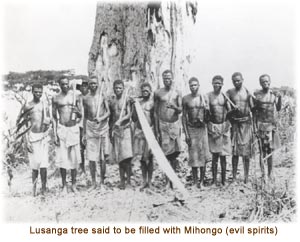

"Mihongo. They say the tree is full of Mihongo."

Mihongo are supposed to be some kind of evil spirits. Perhaps devils or demons would come nearer to describing them than any other English words.

"But you yourself can go, Mbelai?" "No, Chief, I can't go." "Why not?"

"I am afraid. Why, Chief Kabemba, that tree is full of Mihongo. That tree has a word. It talks. The witch doctors go out and ask questions of that tree, and it answers them. I am afraid to cut it down."

"Mbelai, last night I learned that you are not a Christian, that you have two wives, and that in other things too you are doing just like a heathen. Mbelai, you have a great deal more to fear than what that tree can do to you. You had better turn to Jesus Christ, and then you would not need to fear Mihongo."

Mbelai would not be persuaded. He was really afraid. He was sure he would not touch that tree.

Now I was in deep trouble. If the strong men accustomed to handling the axe were afraid to cut down the tree, how could one expect inexperienced men to cut it down?

A conference was arranged. The pastor of the Church and the elders, the four axemen and the six firewood choppers, and two missionaries, were to be present., As we sat in a circle on the grass, we explained that there really were no Mihongo in that tree. The idea of Mihongo was pure delusion. Then we showed that Nzambi, Nvidi Mukulu, the Creator of all things, had put that tree there for the express purpose of building a hospital at Bibanga for helping their sick friends. Therefore the missionaries were determined to get that tree, and we would certainly do it, even if we had to cut it down with our own hands. We also pointed out that if we missionaries did cut down the tree because they were afraid to do it, they would become the laughingstock of all the villages, because the missionaries had done what they did not have the courage to do. After long persuasion, the ten men agreed that they would cut down the tree. It was arranged that the native pastor and I were to accompany them to the tree the first morning, and open the work with prayer.

Consequently, on a morning soon after this, one missionary and one native pastor and ten heathen men with axes went out through the high grass to a tall tree that dominated the landscape for miles around.

With the men in a group near the tree, the pastor and I led in prayer. We thanked Nzambi for putting the tree there for building the hospital, and asked His protection for the men while they pursued their task. Then I took an axe and began to chop.

Church officers took turns staying with the men every day while they chopped, to strengthen their hearts. Day after day they chopped, until the tree was ready to fall. The tree was hard. Sometimes the axes would strike into lumps of petrified sap. Nothing stopped them, and at last I was happy to see the giant lusanga fall with a mighty crash to the ground.

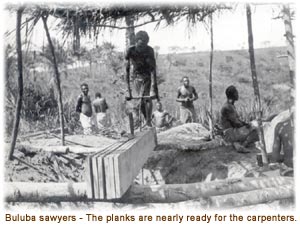

Now, I thought jubilantly, the victory is won. With glad heart I gave directions for the work of the choppers and sawyers who were to turn that huge tree into lumber for the carpenters. They were told to cut a ten-foot length of the trunk up near the branches, where the diameter was only four feet. Other men dug a pit over which the log must be placed for sawing. Others cut a few of the branches to be used as beams across the pit. I left word that when the log was cut it was to be rolled onto the pit, where the choppers could square it for the sawyers. Then I left to attend to other work. Later a messenger came to tell me that twenty men had tried to roll the log toward the pit, and could not budge it. They wanted 30 more men to help them. So I hastened back to the tree to see what could be done. I pointed out that there was no room for any more men around the log. However, it seemed to me that the present problem could easily be solved. It seemed that by doing a little headwork I could impress these men from the long grass with the value of know-how.

But pride goeth before destruction, and sometimes before grievous disappointment. Some men were sent to dig a trench at a given distance from the log, while others cut a small log to lay in the trench. Meanwhile I returned to Bibanga and sent blocks and 1 tackle out to the job. When I arrived I had one tackle block attached by a rope to the log in the trench, the other one to a piece of rope carried over the big log. This was fastened to a plug driven into the far side of the log. When the men pulled on the rope between the tackle blocks, I expected the big log to begin to roll. But alas for the best laid plans! The men pulled heartily, too heartily, in fact, for a tackle block broke. I hastened off on the motorcycle and returned with another tackle block. It was put in place of the broken one. The men pulled. This time the rope broke! ! I rushed back to the station and got a stronger rope. But it was a bit too large for the tackle blocks. Here was a new problem. Confidence in my ability was apt to drop a good deal below par now. I must find a way. The next try was a crude windlass -just two posts in the ground, with a long, thin log behind them. Holes had been bored into the thin log so that pieces of pipe could be inserted as levers for turning the windlass. The pipes were moved from hole to hole as the turning progressed. Everything moved according to plan until the rope became taut. Just at the moment when the log was about to move the rope snapped. All our hopes snapped with it. You will recognize that our situation had now become extremely serious. Best I knew the nearest hardware store was a thousand miles down river. It would take months to get anything from there. There was no hope of help. Returning for a look around the station, I was surprised to find an old log chain. When this was fastened to the windlass hope went soaring. Again something went wrong. Link after link was bursting open. Soon the log chain lay useless on the ground.

Now I was face to face with failure -bleak, hopeless failure. First of all, failure would mean that my employees would think that I could not carry out my plans. It would also mean the loss of thousands of board feet of valuable lumber that was desperately needed for the hospital. It would even mean much more than that. Around the evening fires all over the country it would be said that these white men who had come to tell them about God the Creator, about Jesus the Saviour, had come in conflict with the Mihongo, and that the Mihongo had overcome them. The Mihongo had permitted the tree to be cut down, then had shown their power in refusing these presumptuous white men the benefits they had expected from their hard labor.

Knowing that matters of eternal consequence were at stake, I was praying most earnestly on the way back to the station. I was hoping against hope that some way could be found to move that log. Having already looked all over the hilltop, I persisted in searching for I knew not what. As well look for icebergs at the equator as to look for more equipment on that hill. But at last my eyes rested on some rolls of barbed wire fencing. Why not use that? Putting two stakes in the ground the necessary distance apart, we stretched strand after strand of the barbed wire between them, and finally twisted the strands into a cable. With all those barbs it was an awfully rough cable. It looked as strong as it was rough.

Arrived once more on the scene of action, I had the wondering men put the barbed wire cable on the crude windlass. Again they pulled with a will. The cable began to tighten. It became taut. Still they pulled. Now something must happen, somehow. Happen it did. At last, little by little, the big log began to turn. It moved very, very slowly. The men kept turning the windlass, and finally that heavy log was rolled onto the pit. I calculated that it weighed at least four tons. And did I feel like singing Glory Hallelujah!!!

There was a second big lusanga tree. (Singular is lusanga, plural nsanga.) It was a little larger than the first. It was clearly visible across the 300 feet deep Mutuayi valley, from Bibanga station. In my explorations I had visited that tree. That visit now ensnared me.

Because some of the workers were unskilled men, and there were serious dangers in handling big trees, the chances were ten to one that somebody would be hurt during so long an operation, and that the devils in the tree would be given credit for the accident. When our first tree was nearly finished, I was satisfied that one big tree was enough, and we must content ourselves with sawing smaller trees farther away. The Lord had given us wonderful answers to prayer in helping us handle the first tree, and in protecting all our men so that nobody was hurt in the whole hazardous job. The men knew that I had considered cutting down the Bena Nshimba tree after we had disposed of the Bakwa Tshinene tree. Instead of following that plan I was sending them to cut smaller trees farther away. Why was this? Then a disturbing report reached me. It was said that the people in the heathen villages were saying that the white men had cut down the Bakwa Tshinene tree, but that the Bena Nshimba tree had more Mihongo in it. These Mihongo were more powerful than those in the first big tree. Therefore it was said that the missionaries were afraid of the Bena Nshimba tree. My grandfather was killed by a falling tree being cut down by his own sons. So I had a real dread of a falling tree hurting some of the men. But the report then current was liable to do damage to the basic purpose of all our work. It was as if the people had said, "This man claims to be the servant of the Almighty God, yet he is afraid of the devils in the Bena Nshimba tree." Here was a challenge which could not be evaded. Everybody knew the lumber was much needed at the hospital. A refusal to cut it down when it stood right across the valley looking at me seemed like cowardice and lack of faith. I felt a sense of compulsion to complete what I had so innocently started -a contest with imaginary devils supposed to be living in trees. One might suppose that the men who had successfully cut down one big tree would not fear the second. So I called the kapita Mbelai. "Mbelai, when you cut down that tree at Bakwa Tshinene, did you see any Mihongo?" "Not one." "When the sawyers cut the tree into small boards, did they see any Mihongo?"

"No."

"Well, there were no Mihongo in it, just as we told you. Now there is a big tree over across the Mutuayi. You know the tree. It is the only big tree on that hill. It is the largest tree in this section of the country."

"Oh, yes, I know the tree well."

"Mbelai, there are no Mihongo in that tree either. I want you to go with your men tomorrow morning to cut it down. First come, all of you, to my house. We shall have prayer there. Then go over and cut down the tree."

Next morning Mbelai and all the men reported at my house. I led them in prayer for their protection, and sent them on to their work. Half an hour later Mbelai appeared again at the house.

"Well, Mbelai, what is it now?"

"We want you to come over and pray right beside that tree."

There was nothing to do but start for the tree, big, tall, black Mbelai, heathen woodchopper, and I, a missionary of Christ. Down, down, down we went into the deep valley of the Mutuayi, then up, up the steep hill on the other side, through the high grass until we reached the tree at the top. There the choppers waited for a prayer to assure their safety, before they touched the tree.

There with bowed heads they stood, while I prayed for them. This was no formal prayer, but a heartfelt petition for divine protection for all these men, from all danger. Then I took an axe and began to chop with all my might.

"Did you hear what that woman said?" asked one of the husky axemen, as I paused for a moment of rest.

"No, what did she say?" I asked, as the woman passed on in the winding path through the tall grass along the top of the hills.

"She said that the person who started to cut down this tree would die before night." Since I was the man who started the chopping, this news item held more than passing interest for me.

"So then, if I live until tonight, you will know that is a lie, will you not?"

But these men had been with me for months. They liked me and had a concern for my safety.

"Yes, but, Chief Kabemba, if you don't die tonight, you will die sometime."

"So will the rest of you," I said, and went on chopping. Having chopped enough to assume all the risks myself, I turned over the axe, and the men did all the rest of the work themselves. After about five days of hard work the tree fell.

Those earnest prayers for the protection of the men were answered. It was not uncommon in ordinary cutting and sawing for a man to be hurt once in a while, either by carelessness or by unavoidable accident. I count it nothing less than a wonderful answer to prayer that in the eleven months required to cut those two great nsanga trees into lumber none of those men were injured. For it is quite clear that the heathen people would have credited any serious mishap to the terrible vindictive power of the devils.