During our stay at Luebo we had a guest on the station, the most successful prospector employed by the diamond mining corporation, which held the concession for all diamonds and other minerals in the whole area. He was on our station for medical care, and occasionally had meals at our table. One morning he said he had something to show us if we would clear the dining table. When that was done, he produced a pickle jar half full of rough diamonds. He poured them on the tablecloth and let us examine them. It was really fun to play with hundreds of diamonds, observing the differences between the stones. Times have changed in Congo. That would not happen now.

Traveling through the country one sometimes thought of the diamonds which might be all around. At first it rather annoyed me to think that even if I were to find a diamond I could not keep it. But thinking it over I realized that if finders of diamonds could keep them, the country would soon be filled with the dregs of mankind, who would make the state of the heathen people even worse. So I no longer worry about diamonds.

We were at Luebo when the First World War ended. But we didn't hear about the Armistice until a week later. We did not yet have telegraph, telephone, or wireless at Luebo. The news reached Lusambo by wireless, and was brought to Luebo by foot messenger. It was the most welcome kind of news to all of us foreigners so far away from the outside world.

One of the happy memories of our first stay at Luebo was our acquaintance with Job Lukumuenu, the crippled boy. He could not walk. But his little hut by the wayside was a magnet attracting many people, both American and African. Job was a patient sufferer, and one of the most radiant Christians I have ever known. He was a wonderful influence for Christ among the young people of Luebo, and an encouragement to the missionaries. He died during our first year on the Mission. It could be said of him as of Abel of old, that "he, being dead, yet speaketh."

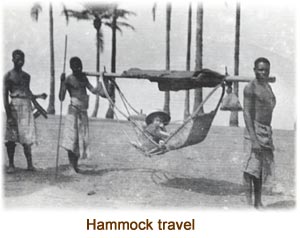

A year after I took charge of the Industrial School the students were given a vacation of three months, and was sent for a short stay at Lusambo. This was a transit point up the Sankuru River, for freight coming up River for the Methodist Mission to the north, and two Presbyterian stations south. So the station had to be kept open. Mr. Stilz, of the Methodist Mission had been sent there. But that was outside of his language area. He needed help from someone who spoke the Tshiluba language. Therefore I was sent for a stay of two months at Lusambo, leaving Mignon and baby Alice at Luebo. I made the long trip overland by hammock. The trip took about 11 days, besides a stopover at our station at Mutoto. The doctor provided me with potassium permanganate for snakebite, with instructions for its use if one of my porters should be bitten. I dreaded giving anyone the heroic treatment prescribed, so I was thankful that on that long trip of about 800 miles before I saw Luebo again, none of my men was bitten. In fact, in all the years I never had to treat a case of snake bite.

I have never been much of a hunter, but took a shotgun with me on this trip. On a bright, sunny morning was being carried through a magnificent, beautiful forest, when the man ahead called that there was an animal nearby. I dismounted and followed the men away from the footpath, where they pointed to a monkey way up in a tree, framed by a circle of foliage, like round window. Africans are quite fond of monkey meat, and as neither they nor I claimed any relationship to the monkeys, I had no objection to shooting one if I could. Taking good aim, I fired. The monkey fell to the ground with a thud. But suddenly I found myself with other and more urgent business. While looking up I had stepped into an army of the dreaded driver ants. They were attacking in force. I had to remove my trousers to pick off those pestiferous invaders. The men had monkey meat that afternoon and were happy.

Nowadays it is almost impossible to find men strong enough, or willing, to carry a hammock. Men who are strong enough for that are likely to go off to work in the mines. But in those days strong men thought it an honor to be on the hammock line, and there was quite an esprit de corps among them. They could travel from 20 to 30 miles a day, and in an emergency they might do 40 miles. Twenty-five miles was a good day.

There were four pairs of men for the hammock, two men carrying at a time, and professionals were so skillful that they could change porters almost imperceptibly as they ran. Men who had carried hammock a long time developed a kind of muscular cushions on both shoulders. It was good entertainment for the villagers when a white man came riding through the town in a hammock, and crowds ran alongside the hammock singing songs. Sometimes my men would sing, "Owner of chickens, look out for your chickens, Kabemba is coming." My Congo name is Kabemba, a species of swift flying chicken hawk, perhaps a kind of falcon, which swoops down to steal a chicken, and is gone before the owner can stop him.

Sometimes village men begged the privilege of helping to carry the hammock. Then they would race along joyfully to show off to the other villagers. On a few occasions my hammock has been dropped by these hammock-happy volunteers, but in each case I escaped injury. I knew of one missionary who suffered a spine injury from such a fall.

I had bought a good camera from Mr. Crane for $25.00. That was a lot of money to a missionary in those days. But I did want pictures. I had taken some on this trip. When we arrived at Mutoto station I arranged to develop a roll of film. When I was all set for development I opened the camera to remove the roll, and found both camera and film watersoaked. All was ruined. At first I could not understand. Then I remembered that we had crossed the Muazangombe the day before. That small river was out of its banks, and the men had to wade through water waist deep before we reached the little bridge. The camera carrier had it tied to his waist, but said not a word about the soaking. It was a painful disappointment to lose both pictures and camera. I received three dollars in trade for my $25.00 camera at Willoughbys in New York.

The visit with my fellow-missionaries at Mutoto over the weekend was a pleasure. On this occasion I assisted in a baptismal service. There were about fifty candidates for baptism. Mr. Crane was in charge of the service. But he was overworked and tired. The baptismal formula is something like this: "Ndi nkubatiza mu dina dia Nzambi tatu, ne dia Yesu Kilistc muan'andi, ne dia Nyuma Muimpe." Saying over the same formula 25 times was wearying to the tongue. It seemed to me that Mr. Crane's tongue was on the verge of slipping, and if he made a mistake somebody would laugh, and spoil the solemnity of the service. So I moved to his side and offered to take over. I baptized the other 25 converts.

Next day I resumed my journey to Lusambo. One night I slept in the guest house in a village recently troubled by leopards. My men were afraid to camp on the verandah, as some of them usually did. They left me alone in my house, advising me to close doors and windows tight on account of the leopard. I could not sleep without air, so I piled up some trunks before the open door, and left the upper half open, hoping the leopard would not find me. He didn't. I was happy when I reached my destination. Mr. Stilz and I were bachelors together for two months. I was lonely for Mignon and our little daughter Alice. The evangelistic work of Lusambo station was in my charge while I was there, teaching Bible classes, preaching, and generally looking after the work of the station.

One day in mid-afternoon I was teaching a Bible class in the grass-roofed chapel. The roof was rather low at the edges, so most of our light was reflected from the ground. It grew darker and darker, until we could not see to read. I told the students we had better get home before the storm broke. We stepped outside, but to our great surprise there was no storm. But it continued to grow darker and darker. There was a total eclipse of the sun. Mr. Stilz got a photograph showing a perfect corona. Some days later I started on my homeward journey, but I was to go out of my way to visit Bibanga station. I arrived there in four or five days. A few days out from Lusambo a village chief asked me in all seriousness whether it was true, as he had heard, that a white man reached up his hand, and covered the sun.

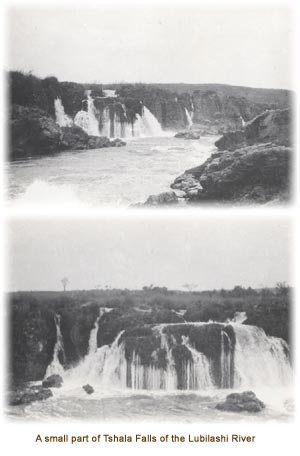

The men had the laugh on me the day we were to arrive at Bibanga. About ten o'clock in the morning they pointed out Bibanga on a high hill in the distance, across the Lubilashi River. It did not look far, so I said we would hurry in so I could have lunch with my friends at Bibanga. They laughed at me. There was the river to cross and long hills to climb. I did not know at that time that Bibanga is nearly 1000 feet higher than the river. So I told the men I could walk in. I walked and walked. We crossed the river in a canoe. The sun was hot, and I started climbing hills. I kept walking until I was too tired for words. Noon passed, and I was hungry, but I kept on walking. Somewhere near two o'clock the men came running with the hammock and said we were nearing the station. They must carry me in with hammock songs. If I walked in they would have plenty of shame. I figured that shame was exactly what they deserved. But I was too tired to argue, so I dropped into the hammock, and they carried me up the last little slope to the station. I spent a few happy days with the McKees and the Kellersbergers and then resumed my long journey, headed now for Luebo via Luluabourg, a distance of 325 miles.

On the way I visited Dr. Motte Martin, of Luebo station, who was out on a long itineration. He fed me well. Incidentally, he had a first-class cook (our cooks are always men), who cooked for him for about 40 years.

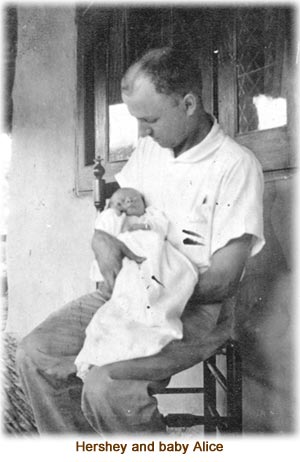

In the course of this journey I called on Kabengele Dibue, chief of the Bakwa Kalonji tribe. Some of our best teachers and preachers had come from his tribe, and I wanted to get acquainted. He was a big, strong man, living in the kind of large compound common to African chiefs, in which there were many huts where his wives lived with their children. There is a division of opinion as to how many wives he actually did have. Someone said he had 300 wives. Someone else said he paid tax on 300, but that he was cheating the government, that he really had 700. I do not know. But I do remember asking one of his sons how many sons the chief had. He said he had 200 sons, but that the chief himself did not know how many daughters he had. On the way I would stop when I could in villages where we had evangelist-teachers. I liked to get acquainted with them and the Christians in the villages. By and by I reached Luebo and Mignon and baby Alice, who was now five months old. Those three months were the longest I ever spent.

It seemed good to be on a larger station again. Missionaries argue as to the relative merits of large or small stations. We have lived happily on both kinds. But certainly the large station gives one the benefit of fellowship and counsel with his colleagues which he misses on the small station.

Our first term was the beginning of friendships which have endured through the many years of our missionary life, and into the evening of our retirement. Being so far away from blood relatives, our missionary group became one great family, bound together by ties of love for Christ and His service. Children recognized this close relationship in the great family of the Mission by calling other missionaries "Uncle" and "Aunt." So through the years we have been known as "Uncle Hershey and Aunt Minnie" by many children of the Mission, and our own children have many "Uncles" and "Aunts" in this happy relationship, which continues through life.

We held some night services at various points away from the station in the big Luebo village. On one of these occasions I was preaching in the dark. On the way home somebody told me I had used the wrong word in my sermon. My text was, "Lay not up for yourselves treasures on earth, but lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven." The correct word for treasure chest was "tshibutshilu." But instead of that I used "tshishihelu" which means altar. Preaching in the dark, my memory slipped.

In December 1919 Mr. Stegall returned to take over the Industrial School. The Mission assigned us to Lusambo for the remaining year of our first term, substituting for the Bedingers, who were on furlough. It was decided that the steamer Lapsley would take us around to Lusambo, which meant sailing down the Lulua and Kasai Rivers to the junction, then up the Sankuru River to Lusambo. Our station was on the riverbank two miles east of Lusambo.

Messrs. Stegall and McElroy had brought two heavy motorcycles back with them from furlough. We saw these come up the hill at Luebo. They were a great marvel to the people, who had seen no vehicle more wonderful than a bicycle. So they followed in shouting, laughing crowds, whenever the motorcycles were started. The McElroys, their children, and one motorcycle accompanied us to Lusambo on the Lapsley. Then they made the long journey to Bibanga as best they could. Paths were very poor, and hills very high and steep. It was a great undertaking to get a motorcycle over those rugged paths.

Except for occasional visitors, we lived alone on Lusambo station that year, which was eventful and crowded with activity. The Commissaire of the District was friendly. He knew some English, having been a liaison officer with the British army in Egypt during the war. It was agreed that he would write me letters in English, and I would write to him in French, and we would correct each other's letters. This would have been very helpful to my small knowledge of French. But we did not get far before he was sent into the interior with an expedition to subdue a cannibal tribe who had the playful habit of shooting with poisoned arrows at white men on passing steamers. I think they had killed one state officer.

In March our daughter Dorothy Anne appeared in our home. The Italian doctor from Lusambo was in town and came to help us, and Miss Hutchinson, a British missionary nurse and trained midwife, also came to stay with us. The Edmistons of our own Mission, going on furlough, stayed with us while waiting for a steamer. Mrs. Edmiston took charge of the housekeeping, and everything connected with the important event went off perfectly. At three o'clock one afternoon some guests to tea left us by canoe. Before five-thirty our baby daughter was safe in bed. We were so thankful to our loving Heavenly Father for His tender care. That baby girl has become a missionary mother in a much disturbed Korea. We might worry for her safety, and for her family. But as we recall how graciously the Lord cared for her then, we are sure He will protect her still.

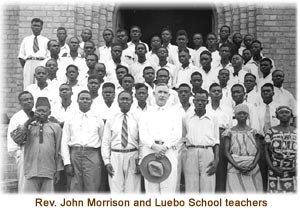

One day at Lusambo we had three callers. The district manager of the SEDEC, a large merchandising corporation, called to introduce two new agents. One of these was Mr. John Morrison, of Glasgow, with whom we became great friends. He later joined our Mission. For 35 years he did great service on our Mission, first as a businessman, later as a minister and educator. He used to come on Sunday afternoons to tea, and we had worship together, and sang hymns. These visits were very refreshing.

Once while Mignon was ill with fever we heard of the death of an American lady who was visiting on the BritishMission 18 miles down river. Mr. Morrison took Europeans from Lusambo to the funeral on the SEDEC steamer. I could not go. When they returned they reported that Mr. Nixon, an old English missionary, was so ill with blackwater fever that in violent chills he shook his whole bed. It seemed certain that he would die. Because I was the only male missionary within a hundred miles, it gave me great concern. Was it not my responsibility to see that he was decently buried? Travel by canoe or on foot was so slow that if I waited for notice of his death I could not get a coffin made and have the burial within 24 hours, as our climatic conditions required. So in my third-rate French I wrote to the manager of the LaCourt Plantation asking whether, in the event of Mr. Nixon's death, they could provide a coffin. They may not have understood exactly what I wanted to say. They at once began to make the coffin. To the surprise of everybody, Mr. Nixon got well. The plantation presented him with his coffin. He kept it for years, but never used it, as he died years later in England.

At Lusambo I was busy enough before the storm which destroyed the Church. I had been preaching and teaching, and had supervision of the outstation work, besides a dispensary with a medical assistant in charge. Then there was transport for the Methodist Mission, as well as Bibanga and Mutoto stations of our own Mission. Caravans of 20 to 100 men would come in to be loaded with boxes of merchandise which I had previously moved from the steamer landing at Lusambo. Then came the storm which blew down the chapel. As Mr. Bedinger, who would soon be back to take over his work, was not a builder, I felt I must build a new chapel before we left for furlough. So I was very, very busy. One day I took a lot of porters to Lusambo to get some freight for the Methodist Mission that had arrived by steamer. But the Administrator of the Territory, in those days of scarce personnel, was loaded with more work than he could possibly do. When I found him sweating under his impossible load, I sent our porters home empty rather than to trouble him while he was checking cargo from the steamer. But as stated before I was too busy. I did not send for the boxes for two weeks. I received notice that I owed demurrage on the cargo because it stayed in the warehouse too long. I was worried, for I had no source of money to pay such a bill. And I was vexed at the injustice of it, when I paid my men to return empty just to help out the overworked Administrator. Feeling as I did, I feared that my poor French might involve me in unpleasantness. I went to see our friend, Mr. Morrison, to ask him to interpret for me, and explain the situation to the Administrator. To my great disappointment Mr. Morrison was out of town. There was no choice. The matter must be handled at once, so I went to the Transport office and did the best I could. The affair was amicably arranged, and I was excused from making payment. But imagine my surprise, before I left town, to be called back to this same Administrator's office. He asked whether I could interpret for him and an American prospector.

It happened that the American was sent by a mining syndicate to explore some territory on which their option was nearing expiration. That section was dangerous because the natives were in revolt, and the government was unwilling to assume any responsibility for the safety of strangers wandering in those parts. This had to be interpreted to the American. He decided to go at his own risk. Never having heard anything more about him, I presume that he survived the hazardous journey. But I am always amused when I think of my having sought an interpreter, then having been asked to serve in the same capacity.

While I was building the chapel, two Methodist missionaries, Messrs. Lynn and Davis, arrived on the way from America to their Mission. They stayed with us a night or two, then went on to Wembo Nyama. They had to leave their trunks, and we had loads for a hundred porters besides. They took pains to explain that when a caravan of carriers came, the first things to send were the trunks from their bedroom. I understood perfectly, but being too busy I forgot. I loaded the caravan with other things. Some days later more men came with the urgent plea, "Please send us our trunks or we may have to dress in barrels."

To folks who stay in their homeland the fluctuations of international exchange may not seem important, but they were one of my real worries all our years in Congo. Ever since the close of the First World War the value of the Belgian franc, as well as many other currencies, has been changing from time to time. During our first few years in Africa, the value of a franc was 19.3 cents, as it used to be given in the dictionaries.

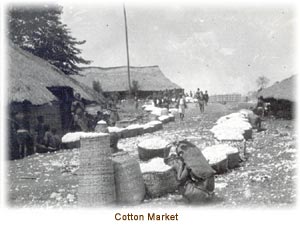

Roughly we figured that a franc was about 20 cents of American money. In those days a workman was paid theoretically 9 francs per month, food allowance included, but practically it was 8 yards of excellent quality white cotton cloth, woven to order, and known as "tshilulu tshia Mission," that is, cloth of the Mission. This was far superior to the shoddy stuff sometimes sold by traders. The people were not working for money. They were working for cloth or salt or soap, or lye for making their own soap. Suddenly the franc began to drop. In a short time its value dropped from 20 cents to 2 1/2 cents, and prices of cloth began to rise sharply. When the fluctuation began we did not understand it, and we supposed nobody else in Congo did either. Far from our other missionaries Mignon and I were alone with the problem. I explained to our people that I supposed the rise in price of cloth was only temporary. But when a man who had been bringing his family eight yards of good cloth per month came home on pay day with only four yards of the same, there was bitterness and complaining in many places. The pastor and elders of the Church kept coming to me for relief for themselves, and for the evangelists and teachers they represented. I lay awake nights, worrying about it. The fact that we had a tablecloth and napkins, and curtains at our windows when the Lord's poor people could not clothe their children, made me miserable. I tried to make the best explanations possible. The words were not cloth. They were not good enough. By and by I was desperate. So when the leaders came one more time, I broke down and wept. I told them it was not in my power to help them but I did feel for them in their trouble. And to show my sympathy explained that practically all my earthly possessions were right in that house. They could come and take everything we had. That was the limit of what I could do. They were deeply touched by my suffering, and said they would not bother me any more about it. They did not want my things, and took nothing from me. And they kept their word. I suffered still. For I knew that the trouble in their homes was still there. I looked with unhappiness on every bit of cloth we had around the house.

And all through the years, whenever the exchange rate has been altered in the money markets of the world, it has given me pain. Whoever gained through those transactions was doing so at the expense of our poor Africans.

One of our experiences while alone at Lusambo lingers in memory as an illustration of the simple faith of African Christians and God's response to their prayers. Little Alice was quite ill. We did the best we could in the way of treatment, but did wish that our Mission doctors had been within reach to give us advice. But Alice grew worse, and Mignon and I knew that her condition was critical. So as I was leaving for the sunrise prayer meeting Mignon suggested that I call on the group at the meeting to pray for Alice. I presented the request, and the people prayed for her recovery. When I returned to the house Mignon told me there was a sudden change in Alice's condition. At first she thought the child might be dying. Soon it became clear that it was a change for the better, and at once she was on her way to recovery. Later Alice was a missionary nurse in Congo, then the wife of a minister in Missouri. We are sure she is living and serving in answer to the prayers of our African friends.

At Lusambo we had as a co-worker the pastor Musonguela. He was a fine Christian. So it was a joy to us to have him baptize our baby daughter Dorothy Anne, called Konkolonka by the native people. This was one more tie binding us to the people to whom we ministered in the name of Christ.

Our station near Lusambo was just a good stone's throw from the river, near the junction of the Sankuru and Lubi Rivers. One day a man was carried up on the station, the worst wounded person I ever saw. He had about twenty wounds on his body, some of them just large holes, others gashes as much as six inches long. His throat had been torn open, so when he breathed the air gurgled out of his windpipe. He looked like a hopeless case. I asked our dispensary boy what we could do. He said to call the pastor Musonguela, who had been a hospital assistant before he entered the ministry. The pastor looked the man over, then advised me not to touch him. His reason was that we did not have what was necessary for the proper stitching of the wounds. It was highly probable the man would die anyhow, and if he did, I would be blamed for his death. Musonguela advised me to send him to the government doctor at Lusambo Hospital. I did so, and was surprised and pleased to learn that the patient recovered. He had enough wounds to kill five white men.

We were told he had been swimming in the Lubi River, where the crocodile had caught him. His friends had intervened and clubbed the crocodile until it let the man go.

Because Mignon twice had bacillary dysentery, Dr. Stixrud gave me a vial of Pasteur treatment for that deadly disease if she should again be infected. Though I had never given an injection he instructed me so I could give it if necessary. By and by the wife of one of the deacons became exceedingly ill with the same disease. It was clear that her days were few if she were not treated. I was concerned for Mignon's safety. But we talked it over and she decided that it would be best to trust the Lord for our own future, and use this medicine to save this Christian woman's life. I followed the instructions and gave the injection to this wife and mother who were in desperate need. It was promptly effective and without doubt saved a life. We were so thankful we made that decision, for Mignon was spared from any more dysentery of that type.

I got the chapel built, then it was time to go on furlough. We were looking for the return of the Bedingers. But we had no news. Finally it seemed we might have to leave before they arrived. That would have presented great difficulties, but we prepared for that eventuality. But they happened to come up river on the same steamer which was to take us down.

Those were busy days for all, specially for the ladies. We had some Methodist missionaries as guests, waiting for the same steamer with us. Mignon had to be hostess to everybody the first two days, then pack up our things the latter two days. Mrs. Bedinger was unpacking the first two days, then she was hostess the latter two days. I had to turn over all the station affairs to Mr. Bedinger. Then we started for our first furlough.

During our year at Lusambo two of our missionary families had lost children by tropical diseases as they passed through lower Congo. So there naturally was a question whether our dear little girls would get out of Congo with their lives. Mignon was sure that if we ever got them safely out of Congo she would never bring them back to such a dangerous country. She would leave them with relatives in America. Indeed, it was then the common practice for missionaries from Europe and America to leave their children in the homeland when they returned after furlough. But before we were past Belgium on the way home their mother was already writing down reasons why we should bring the girls back with us to Congo. And they did return, and they are still alive, thank God!!

The trip down river was not particularly enjoyable. We did have the agreeable company of friends from the Methodist Mission. But the redheaded river captain was not a man after our own hearts. He was very rough with his crew, and did not seem at all friendly to us. We had as a fellow passenger the wife of a businessman, who stayed on his job while she went to Belgium. Once I had reason to see the captain on the bridge, and found him sitting there with this young woman in his lap. Nothing was said about this unusual form of caring for passengers. She told us later that the captain was just like a father to her. We were thoroughly disgusted.

The captain's roughness brought us trouble the last night of the voyage. The steamer was tied up for the night at a large plantation bordering the Congo River. This was also a refueling post, and there were long stacks of firewood for sale. Some of it was brought on board, while the 70 unarmed soldiers who were lower-deck passengers, and other native passengers, installed themselves around campfires on shore. As the next day would be a busy one, I retired soon after dinner. Mignon waked me to say there was trouble on shore. I took a look, and saw a great fight going on; possibly 150 men, or even more, were bombarding each other with chunks of firewood, and with burning brands from the campfires. The flying firebrands against the dark sky made it look like a Fourth of July celebration. Then someone threw a firebrand on the thatched roof of a large warehouse, and suddenly the whole scene was brightly illuminated as the roof blazed furiously. It was evident that if one man were killed it would mean the death of many before morning, and the whole area could become involved. So I rushed out as I was, barefoot, dressed in white pajamas, to try to stop the fight before blood was shed. Along the deck and down the stairs I ran, across the gangplank and into the midst of the fighters. The people knew I was a missionary, and that missionaries were their friends. None of them would willingly hurt me. I did not know the languages of these tribes. I motioned the fighters away from each other as I ran back and forth, trying to get the fighters out of the melee. Finally I got the sides separated, and motioned for all the people from the ship to go back on board. Then I shooed the local people back to the village. All the while the captain had been blowing his shrill call whistle. Nobody paid any attention to him. He had completely lost control of the situation. At long last things got quiet. Knowing how furiously angry the people were, I placed a sentry at each end of the gangplank, and decided to sit on the upper deck overlooking the gangplank all night long to make sure the fighting had not resumed. By that time I felt sure that our own safety, and that of the ship, would be threatened if the fighting broke out again, and the population of surrounding villages also become involved.

Before settling for the night on a steamer chair, I went in to bathe my muddy bare feet. By this time I was aware that I probably had two fractured ribs. It felt like that when I drew breath for about two weeks. When I washed my feet I found blisters from the burning coals of the campfires. In the excitement I had not felt them as long as the burns were covered with mud.

At dawn I felt that my task was done, and went to get some rest. The captain and a few passengers with the plantation owners drew up legal documents about the damage caused by the warehouse fire. We never knew who paid the reported loss of $2000.00.

When the cables were being loosed for our departure, a woman ran out from behind a hut and struck one of the steamer's workmen with a club, leaving a gash on his neck that required about a half dozen stitches.

The best we could learn about the origin of the fight was that a quarrel started between our captain and the foreman of the fire wood cutters from on shore. The captain became angry and threw the foreman downstairs. The latter returned and threw a brick at the captain, injuring his foot. Then members of the crew put him off the boat, and the fight started.

Strangely enough the captain never said a word to me about the fight. I did not wish to embarrass him by speaking of it. But when we reached our destination at Kinshasa, we could find no hotel accommodations. He kindly allowed our party of missionaries to stay on board ship for the night, taking us on to Leopoldville, the next stop. Next morning when I could not get porters to transfer our baggage to the railroad station he went further and allowed the ship's crew to help move it. This, I took it, was his mute way of expressing gratitude to me for pacifying the angry mob.

At that time the railway trip to Matadi still took two days. The night between was spent at ThysvilIe. When we were safely aboard the train I thought our troubles were over. But in the afternoon our train was stopped because of a freight wreck ahead. We learned we must spend the night on the train out there in the jungle. Our second-class coach was crowded and dirty with smoke and soot. We knew the crying of our children would keep the other passengers awake. I went to the conductor, a West African coastman, asking to pay the difference in fare and transfer to first class. He said it could not be done. The day in the hot, smoky, dirty train had left me looking very disreputable. So I was both embarrassed and surprised to be called by a gentleman in a private car. He was the Director of the Banque du Congo Belge, the foremost banker in the Congo. Accompanied by a physician, he was taking his wife to Matadi to board the ship for Belgium. They had overheard me talking to the conductor. Recognizing our unfortunate plight, they generously offered that my wife and babies might occupy places in their private car for the night. Never was help in need more appreciated than that generous offer. We had with us screened beds for the children, and I set them up in one end of the banker's car, so Mignon and the little girls got some rest. Other passengers in our car, and I, also got more rest than would otherwise have been possible. Instead of reaching Thysville Friday evening we arrived on Saturday morning at ten o'clock. By that time Mignon had a fever. The Methodist missionaries helped nurse her and the children over the weekend. Monday morning the train resumed its journey to Matadi.

In those days it was necessary to carry with us much money for the long journey. I had the money and important papers in a briefcase. To make sure I would not forget it, I set it between my foot and the leg of the table at breakfast. It was a hurried meal, for we had to eat, then rush downhill to the train to make sure of seats. But the events of the past days had wearied me. We ate. With handbags, one convalescent wife and two small children I was off for the train. Halfway down the hill a Negro boy caught up with me, held out the briefcase, and asked, "Is it yours?" Without prompt and honest action by that boy we would have had much trouble and expense, besides the loss of all that money. We would have missed our steamer at Matadi, thus having a delay of three weeks there with great danger to the children's health, and many other inconveniences. The boy was a hero. He will never know how much good he accomplished by a prompt use of his head and feet. What reward I gave him I cannot recall, but I hope it was enough.

We reached Matadi and again found no hotel room. We were given space for the night upstairs in a gloomy, dirty warehouse. But there was reason to be grateful even for that. It was far better than spending the night on the street. Matadi is one of the earth's hotspots. Its name means rocks. It is really a great deep bowl of rocks right under the tropical sun, and rarely has a breeze down near the docks. It gets hot all day and stays hot all night. We spent a very uncomfortable night. In the morning we were happy to get aboard ship and sail for Belgium. It was the end of our first term in Congo. Five more were to follow.