We entered the broad mouth of the Congo River a month later than expected. The little steamer Hirondelle had brought us, in two days and a night, from St. Paul de Loanda, a Portuguese port in Angola. We were more than twenty passengers on the open upper deck, and there was not a cabin of any sort for any of us. We sat in steamer chairs day and night, and had our meals right there on the deck. The lower deck was occupied by a herd of cattle, who made their presence known in several disagreeable ways. The surface of the ocean was smooth as glass, but the gentle swells rolled our little ship and made many of us seasick. We were happy indeed to see the waters of the great river. The low lying lands near the mouth of the Congo are too flat to make attractive scenery, yet the mere fact of being in Congo gave us much satisfaction. Deck weary as we were, we had great hopes of getting to the hotel at Boma and sleeping in beds for the night. But that was not to be. Many passengers from Belgium on the good ship Albertville had the same idea. They got there first, and took all the rooms. So we had no place to go but the station of the Christian and Missionary Alliance. Some of their missionaries had traveled with us three months since we left New York, and they arranged for all but two of us to spend the night at their Mission. Since there was not enough room for our big party, the ladies and the two babies were given beds in the homes, and the men slept as best they could on the benches in the Church. How hard those benches were I do not know, for I was one of the two volunteers to stay on board ship and guard our baggage, which was all on the open deck. Mr. Allen and I fixed our steamer chairs with mosquito nets, and settled for the night. But an unexpected tropical rain came down, and we waked to find ourselves drenched and shivering. That was my first night in Congo.

The next day our steamer took us up river to Matadi, at the head of navigation for ocean ships. The scenery between Boma and Matadi was impressively beautiful, for the great, deep river, winds among high, rugged hills. One point in the river is called the Devil's Cauldron, an exceedingly dangerous whirlpool. Here ships inexpertly handled would turn every way, and could easily be wrecked. We passed the old British Baptist Underhill Station where our pioneer missionary Samuel N. Lapsley was buried after a very brief service for Christ in Congo. In his day Congo was known as the white man's grave. Even as we entered the country we had no hope of serving there as long as 33 years.

Having landed at Matadi there was much to be done. Happily for our party Dr. Stixrud and Mr. Allen had been in Congo before, and knew what must be done. They arranged about railway tickets and customs formalities. As all hotels were crowded they found rooms for us in a wretched old hotel annex. We had to be careful not to fall through the rotten porch.

Next day we started on the two-day train trip on the narrow gauge railroad, spending the night at Thysville, a mountain town. It should be explained that from Stanley Pool to Matadi the mighty Congo breaks through the mountains in a series of cataracts which make navigation impossible, and which long retarded the development of that magnificent country lying east of the mountains. It was opened to the world by the labors of David Livingstone and Stanley. Until this narrow-gauge railroad was built, access to the interior was next to impossible. The little railroad through the mountains was very important, for this was the bottleneck of the Congo. It was said that the annual dividend amounted to one hundred per cent of the original cost, which was very great. But years had passed, and the equipment was old. The stockholders cared more for dividends than for the comfort of the passengers, so the service was terrible. The dilapidated second-class coach in which we rode had seats for only twelve passengers. For those two days it carried fourteen adults and two babies, and was stacked with hand baggage and lunch boxes and drinking water and ice. The chairs when new had been good enough. Now they were old and worn-out, and by reason of the lurching of the train for many years had lost their moorings, so we were bounced around. It was hot for much of the way. The soot which came in the windows stuck to our sweaty faces until we were black. More drops of perspiration ran down our cheeks, leaving rivers of white which made us look like coal miners from a very warm mine. As the engine burned firewood, and often used forced draft, the trip was far from monotonous. As it chugged bravely up the steep grades, sparks poured from the smokestack and blew in at the car windows, and now and again somebody's clothes caught fire. No serious damage was done; only little holes in clothing here and there, and sometimes small burns on somebody's skin.

In spite of all the discomfort, we have kept with us the memory of many scenes that delighted us as new arrivals in Congo. Everything was novel and different. Here we unexpectedly crossed a bridge which commanded a view that was breathtakingly beautiful. There were lovely waterfalls, and along the way there was much of the tropical forest primeval. The hardships of the train trip faded when we were reminded that for years people had to enter Congo without a railroad. So our little train was glorified by the contrast. By comparison with earlier days we were traveling in the lap of luxury.

On the evening of the second day we were happy to reach the river village then called Kinshasa, now a part of the great city of Leopoldville (above 300, 000 population). Here we found Stanley Pool, a lake of considerable size formed by the natural barriers in the Congo River before it makes its first leap of the hundreds of miles of cataracts on its way to the sea. Kinshasa in those days was little more than a busy junction point for the river steamers which sailed the upper Congo and its great tributaries, and the railroad which at that time was the only means of travel between the immense interior Congo basin and the outside world. Here we found our forty-ton Mission steamer, the Samuel N. Lapsley, waiting for us. There were sixteen passengers, and that was a crowd. Nobody slept in the bathtub, but we did sleep nearly everywhere else. Some of us slept on cots on the deck. It was a happy party, and the sixteen days of the voyage passed pleasantly. We were at last among crew members whose maternal language we had been studying, and hearing them speak it was a great experience for us new missionaries.

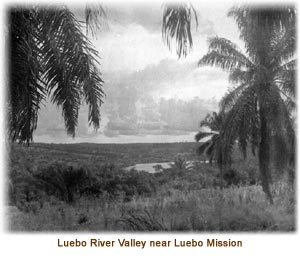

It was a disappointment that we could not reach Luebo for Christmas. We were four days late. As a consolation an elephant brought her baby to the river for a Christmas morning bath, close to the course of the steamer. Those are the only elephants I have seen in all these years in Congo, though I crossed their tracks many times.

There were occasional villages of woodcutters on the forested banks of the Congo and Kasai Rivers, but it was cheaper to cut our own firewood for the steam boiler. Every evening when the steamer anchored for the night there was a great rush of woodcutters from the lower deck, hurrying into the forest to get their quotas of wood ready to be loaded in the morning. They worked into the night, and lying awake we could hear the sound of the axes far and near. After the wood was loaded early in the morning, cutters went to sleep for the day, while the Lapsley steamed the river.

Their sleep was sometimes broken by a call to man the rowboat, which served in emergencies. The Kasai River at some points is very wide and comparatively shallow. Sandbars shift their positions and the river cuts new channels between them. Frequently steamers got stuck in the sand. Then an anchor was carried to some point, with a cable attached to the hand winch the ship. It was hard work in the burning sun cranking the winch until the steamer was pulled loose from the sand. These delays were hot for the passengers, but even hotter for the sweating crew. While the movement of the steamer provided a breeze when in motion, a stationary steamer can be a very hot spot. To avoid such experiences, sounders with bamboo rods sat at the front of the ship, testing the depth of the water and calling out their reports.

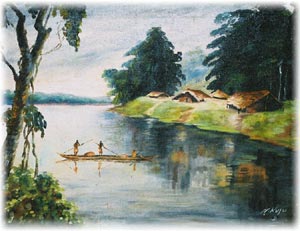

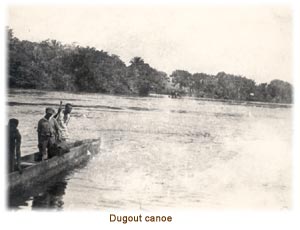

The views as one ascends the Congo and Kasai Rivers change constantly. Sometimes there are flat, grassy plains, and occasionally what look like swamps; but for the most part the river valleys are heavily forested, so that each turn brings new visions of tropical beauty. The forests take on added interest, for who knows when you may see monkeys playing in the trees, or brilliantly colored tropical birds. Sharp eyes would reveal crocodiles which to the casual passerby would not be visible. Often they would lie on logs, where it was hard to see the line between the log and its occupant. There were many hippopotami. Seeing them brought new thrills to the passengers. Occasionally there would be a village on the bank, but usually the people lived back from the rivers, hidden by the dense forests. We met few steamers, but canoes on the river were always an attraction, often of graceful shapes. They were hollowed out of big trees with prodigious labor. They showed careful workmanship and an eye for the beautiful. Such results from tools of primitive type indicated real talent and artistic taste. It was a delight to see how skillfully the paddlers maintained their balance in the canoes, often standing in such precarious positions that the observer felt sure they would fall into the river. They worked with perfect rhythm as they paddled together.

Once in a while one saw an old shell of a canoe rotted to the water's edge, and wondered at the recklessness of those who risked their lives in such a boat. Even for strong swimmers there remained the appalling hazard of being caught by a crocodile. Years later we were aboard a large river steamer where two men had a fight on the lower deck. One pushed the other overboard. The powerful engines were stopped, and a lifeboat was sent to rescue the man swimming in the river. We almost held our breath while the lifeboat, now quite a distance behind us, drew nearer and nearer to the lone swimmer. Suddenly, before the rescuers reached him, the man disappeared, and though the search was continued for some time, he was never found. Probably a crocodile took him under, first drowning him, then taking him off to be eaten at leisure.

A daily thrill of life on the steamer was the hearing and learning of new words. We were traveling with many natives who spoke the Tshiluba language which we had been studying for some months. Learning a language from books is one thing. Absorbing it through the ears from people who speak nothing else is entirely different. So our language study had come to life, and the days passed quickly.

One day the other men were making a pastime of cutting each other's hair. Jim Allen had made a wreck of John Stockwell's hair. They called and asked me whether I could cut hair. Saying I never had, I went for a look, and decided it could not be made to look any worse. So I was persuaded to try. It was agreed I had improved it a little.

We left our Methodist passengers at the mouth of the Sankuru River, while we continued up the Kasai, then up the Lulua River. Excitement rose as we approached our destination.

Colleagues at Luebo were anxiously awaiting our arrival. So when the Lapsley blew her whistle down river they and the native people were ready to welcome us. As the steamer came around the last bend of the river near sunset, we could see thousands of people on the riverbank. They were singing Christian hymns in their own language to welcome us. This to us was the sweetest music we had ever heard. Our journey of four months was at an end on December 29, 1917.

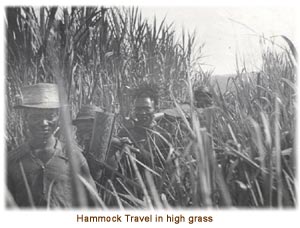

The hammock was the only conveyance available at that time for travel on land. It was swung beneath a bamboo pole carried on the shoulders of two strong African men. There was not a vehicle of any kind in great areas of interior Africa. There were no roads except village streets and footpaths. Most of the latter were not even safe for a bicycle. They were narrow and crooked, and had unexpected holes and dangerous obstacles in the grass. So one could choose between traveling on his own feet and those of his African friends. For my part, I had just about decided in advance that I would travel on my own, for I did not like the idea of being carried. But it happened that the day we arrived I had not been well, so I did not argue when someone urged me into a hammock. The next thing I knew the husky porters were happily carrying me up the long high hill. This was the first of hundreds of miles spent in the hammock.

It was Saturday evening, and night had fallen before we reached the Mission station at the top of the hill. We were enthusiastically welcomed, and despite wartime shortages we were feasted and made to feel at home in these strange new surroundings.

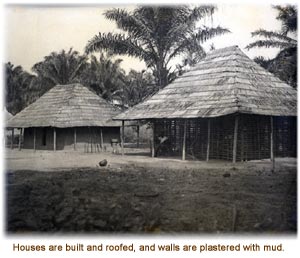

We wakened to a beautiful Sabbath morning. We saw the missionary homes, built with sticks from the forest and plastered with mud, and roofed with palm leaves or long grass. The large station had an abundance of beautiful palms and lovely mango trees. On the west side was the hospital, where for 25 years our Dr. Stixrud and his wife did a magnificent work, evoking the gratitude of government officials, traders, diamond miners, and many thousands of the native people. Many years later when I mentioned his death to a Russian trader who had inquired about Dr. Stixrud, the man burst into tears. Dr. Stixrud still had most of his service before him.

At that time it was reported that Luebo had the largest Presbyterian Church in the world. Worship was held in a large pavilion covered with palm leaves and filled with backless benches seating two thousand worshippers. It was a great joy to attend our first service there. The people were as glad to see us as we were to see them. The order, for so great a crowd, was amazingly good, and in marked contrast with their behavior in the market, where they are exuberantly noisy. No doubt some of the difference was due to the presence of ushers with long bamboo shoots with which they could reach and gently tap on the head of anyone disposed to fidget.

Dr. William Morrison preached. We did not yet hear readily, and it would be some time before we could easily understand preaching. But just to sit there and feel that at last we had arrived was very satisfying. We were introduced to the congregation, and said a few words of greeting.

For days and weeks we were being mentally photographed by thousands of eyes as we went about our various duties. Years later I had a sample of what that mental photography means to the native African. I took on a new boy at the Press. When I asked about his tribe I found he came from far back in the Bibanga territory. I told him that I had visited his tribe nine years before. He replied that I had visited his own village, that it was Wednesday evening, and that I was riding a motorcycle. Our Congo history is written in the memories of thousands of people. Sometimes they know more about us than we know about ourselves.

It was our good fortune to arrive on the Mission during the lifetime of Dr. Morrison, one of the most notable missionaries Congo ever had. He had been on the field about 21 years, had written an excellent Grammar and Dictionary of the Buluba (now called Tshiluba) language, and translated large parts of the Bible into that tongue. He had also prepared a book called the Malesona, a series of lessons from the beginning to the end of the Bible, giving much space to the studies concerning Jesus and His teachings. This book was the only Bible the people had on our arrival. They now have the entire Bible in their language, largely as a result of Dr. Morrison's labors, supplemented by the able work of Dr. T. C. Vinson.

Dr. Morrison was not only grammarian, translator, and writer. He was in every sense the leader of the Mission, which at that time had about seventy missionaries. He was a man of prayer. He carried to the throne of grace not only his own problems, but those of the Mission as a whole, and the individual burdens of other missionaries as well. He was killed by overwork at the height of his usefulness, tropical dysentery being merely a contributory cause of his death. He was truly a great man with extraordinary gifts of vision, of sympathy, and of power. He loved people, and he was always helping others.

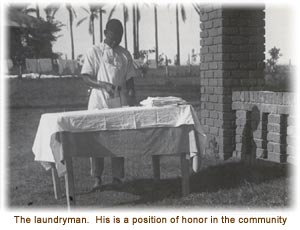

Dr. Morrison helped us most by one little word of advice. He probably observed that Mignon and I had been brought up to look after ourselves and found it strange to have servants to help us. His advice was this: Never do anything yourself you can get a native to do. At first this sounded strange, but the more we considered it the more we realized the wisdom of his counsel. We built our lives on that foundation, and I have no doubt our usefulness in Africa has been multiplied for that reason. This released missionary time and energy for doing important things which were crying to be done, which otherwise would have remained undone.

It was wartime. Supplies were hard to get. Those ordered from abroad were likely to be sent to the bottom of the sea by mines and submarines. There was no cook stove for us, and my first job was to design and build a stove of brick, mud and sheet iron.

Sugar was practically unobtainable; but the native people raised some sugar cane and I was asked to design and build something that would squeeze out the juice. Wooden rollers were mounted between two slabs of wood planted in the ground. One roller had a crank at one end; the other a crank at the opposite end. With this we were able to extract the juice after the cane was partly chopped with machetes. We made very little sugar, but quite a bit of syrup which helped sweeten the life of the station.

Because of the climate, wheat does not grow in our part of Africa. During and after World War I it was hard to get flour. Manioc was used in various ways. Flour was made also from sweet potatoes, millet, and whatever people could adapt to the purpose. Happily, eggs and chickens were plentiful and cheap, at that time. Milk had to be imported from Europe. There was not a cow within 100 miles of Luebo. Some fly carried a germ that killed cattle.

I had left the pastorate of a Church in Louisville to become a missionary. My purpose was to preach the Gospel of Christ to the Africans. But because I had been educated as a carpenter before preparing for the ministry the Mission asked me to major on the Industrial School and sawmill during Mr. Stegall's absence on furlough. I had four months to learn those two jobs.

We were expecting to entertain the General Conference of Protestant Missions at our station in March, and the preparations took quite a bit of time. But I was determined to preach. The only time I had was on Sundays. So before four months were finished I started to go across two rivers, where there would be no missionaries to notice my linguistic errors, and preach as best I could in Tshiluba. I would read a Bible lesson from the Malesona book, then start to explain. When I got stuck for a word, I would stop and ask one of the hearers what I wanted to say. Then I resumed; a good way to build up a vocabulary in a strange language!

On one of these preaching trips I crossed the rivers in a large dugout canoe. To save time we went down the Lulua River, to its junction with the Luebo River, then up the Luebo to our landing. The canoe had a hole in the bottom that had been patched up with mud and grass. When we got into the swift current where the rivers met, the plug came out of the bottom of the boat, and a large stream of water began to rush in. The boatmen worked hard to get us to the nearest bank before the boat could fill. I did not want to try swimming, for I really was not much of a swimmer. Besides a crocodile had killed and eaten about seven persons in that very neighborhood not too long before.

One Sunday, after preaching in a village, the chief told me he had a sick man in the community but that the boatmen refused to take him across to the hospital. This vexed me, as it seemed unmerciful to let a man suffer practically in sight of our Mission hospital. I asked to see the sick man. The chief and a large group of people started out to show me where he was. But the farther we went the more our group dwindled. Even the chief disappeared. At last I found myself at the far end of the village. My guide led me through the tall grass, then pointed me to a few people who were scrubbing a man with sand and water. He had white spots all over his black skin. It was the first case of smallpox I had ever seen. I stood at some distance and prayed for him, but I now understood why the boatmen refused to transport him.

The big General Conference of Protestant Missions in Congo came and went. It was a great occasion. The Belgian Congo enjoyed the best missionary cooperation in the world. Overlapping of missionary work was kept to a minimum. The Congo Protestant Council tries to allot territory in such a way that there is no competition between the various Protest Societies. Baptists work in one language, Presbyterians in another while Methodists, Mennonites, Disciples of Christ, and others, each have their own language areas. The 1918 Conference was the greatest held up to that time. Missionaries from many societies and a number of different countries were present. Our own Dr. Morrison was outstanding among them, and this Conference, the high point of his remarkable career. Soon after the departure of our guests he went to be with Christ.

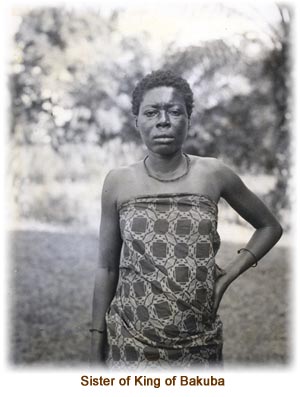

The death of Dr. Morrison brought great sorrow to missionaries and natives alike. He was loved and respected by all, and was a bulwark of strength to the whole Mission. The dysentery which took his life also took many others. There was a veritable epidemic of the dreadful disease in the Bakuba kingdom around Bulape station, where our Mr. Washburn and Miss Fair did a marvelous work in stamping out the disease. After the disease entered his harem the king himself was stricken. The king's mother then had a blacksmith remove from the king's ankle the copper circle which is like the crown in that kingdom, and sent it to Mr. Washburn, thus making him temporarily king of the Bakuba. The Lukengu historically had held the power of life and death over his subjects, this gave Mr. Washburn all the power he needed to enforce sanitary laws and make treatment effective. He promulgated and put in operation a rigid code of sanitation which was enforced by heavy fines for those who refused to obey. Infected houses were burned, infected persons were placed in segregated camps for treatment, and so the epidemic was stayed, and thousands of lives were saved.

During that first year I helped make the coffins for Dr. Morrison and some native Church leaders, and some missionary children. I then had the feeling that few of us would live twenty years, and that five years might be the life expectancy in so deadly a country. We did not suppose we could possibly live 33 years. Tropical medicine has made great advances during these years, and many of our missionaries have already been there 25 or 30 years, some even more than 40 years. Yet Congo is not in any case a health resort, and those who go there must always be fighting tropical diseases.

In those days we had only slow surface mail service to the outside world. Mail came and went only by ocean steamers, and these came at irregular intervals. Once we waited three months for our mail from America. Another time we received a letter which had traveled around six months before it reached us. We knew a British lady who said that when she received thirty letters at a time she opened one a day for thirty days to enjoy them more. But most of us were willing to enjoy them less and open them all the same day to find out what was going on in the world, and especially in America.

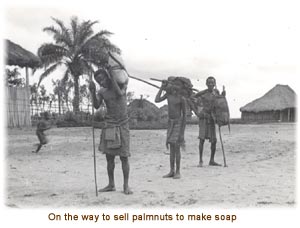

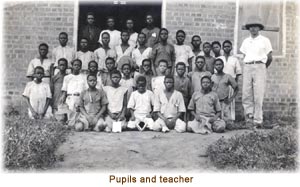

While the primary objective of our Mission has always been to preach the Gospel of salvation through Jesus Christ, we recognize that temporal benefits also do "accompany and flow from salvation." We found the people sitting on the ground, eating on the ground, and many of them were sleeping on mats or beds made of sticks tied together in a very crude way. The huts had very rough and unsatisfactory makeshifts for doors, and usually they had no windows. The people were barefoot, and while shoes were not needed on account of cold, they were a help in protecting the feet against the burning hot sand of the paths at noonday. But the chief value of shoes is that they protect against injuries to the toes, and reduce the hazards of certain tropical diseases which enter the system through the feet. It was thought that the whole life of the people could be elevated and improved by having an Industrial School. Mr. Stegall, from Georgia Tech, was the founder of this institution. When I took over for the duration of his furlough the School had departments in shoemaking, tanning, tailoring, cabinetmaking, carpentry and bricklaying. Some of the early teachers came from the West Coast of Africa. The students who entered the School must already know how to read and write, and know something of arithmetic. But schooling was continued along with shop work and Bible instruction.

Because it will not come up elsewhere I may digress here to say that the results of our effort were different from what we had planned. Large corporations financed from Brussels, London and New York were coming into the country to mine diamonds and copper, produce palm oil, and build a railroad. All of the projects called for skilled labor. Recruiters scoured the country to hire every man who could drive a nail well, or saw or plane lumber. Good wages were offered. Instead of remaining in his home town to make beds and tables and chairs and doors and window shutters, our graduate was persuaded to go away, often far away, to work for corporations, or for traders who were opening trading posts throughout the country. This tendency was strengthened by the fact that while in the home town the graduate could find many customers for his products, it was usually difficult to collect from neighbors. If he worked for the white man he could expect regular pay for his work. So our well intended plan for improving village life through the Industrial School failed to accomplish its primary purpose.

In the late twenties circumstances necessitated the temporary closing of the School. Then came the financial depression of the thirties, which deprived us of the means to reopen it. In view of the aforementioned conditions the closing then became permanent. When funds became available simpler and less costly courses were introduced to accomplish our original objective of improving living standards in the villages from which our students came. As part of the day school program this help could be given to a greater number of students.

Mr. Stegall was gone before the School reopened after vacation. I was well fitted to teach cabinetmaking and carpentry. And Luhata, the first graduate of the school, made a very good teacher. In shoemaking we had a West Coast man as instructor. I too knew something about soling shoes, having learned before I went to the Kentucky mountains. Of tanning leather I knew only what Mr. Stegall had shown me. There were tanks in which hides were treated with the juice of the bark of certain trees from the forest. Our shoemaking suffered a handicap because tropical hides are not so thick and tough as those grown in cold climates. The leather therefore was not so strong as I expected. With bricklaying I was not well acquainted, but we had a mason from the West Coast. If we had been working with lime or cement for mortar our brickwork would have been better. I planned and erected a school building using burned bricks with mud for mortar. The design was not strong enough for mud-mortar walls and pillars. So when a heavy tile roof was later put on the building it threatened to collapse, and happily was pulled down without injury to anyone. Of tailoring I was ignorant, so Mignon kindly took supervision of that department.

There was a heavy load of detail connected with the Industrial School. The purchase and cooking of food was part of the work. As about two days per week had to be given to the sawmill down in the forest, there was far too little time for all I had to do at the School.

One of our worries was termites. They are most prolific in Congo, and must constantly be reckoned with. A government officer was in urgent need of his shoes sent us for resoling. We did a rush job, and I had the shoes sent to my house, and set them at my bedside, so I would see and send them to the owner first thing in the morning. Picking them up to send them I found that the termites had come up through the mat from the dirt floor during the night, and eaten away a good part of the soles. The job had to be done over again.

While writing of the Industrial School I must mention the problem of discipline which faced me immediately after I took charge of the School. Before his departure Mr. Stegall sent the boys on vacation, with very strict orders about their return. On a certain afternoon they were to return to their dormitories, and report to me next morning. Staying in the village that night was strictly forbidden. But many of the boys thought they would have some fun by staying out that night, and seeing what the new boss was made of. At my home and at Williamson School I was reared to obedience. At the latter place such behavior would have been followed by immediate expulsion. What some might have considered a boyish prank did not seem the least bit funny to me. My first problem was one of discipline, and it seemed certain that if I dealt lightly with the present insubordination, I would have constant trouble in future. To my mind disobedience to constituted authority was intolerable. It was not only inconvenient, but it would be bad for the souls of all who disobeyed. A battle had to be fought for law and order, and if the battle had been lost School would suffer permanent injury.

I decided not to penalize anybody for this first offense. So after duly considering the problem I called up the students and gave them a lecture on the necessity of obedience. I let them know I had come across the great waters to help them. But to help I must have obedience. If I could not get obedience I would rather return to my home country than to attempt to carry on. I lined up the hundred boys, and told them that each one who wished to remain in the School must come before me and promise, "I want to do what you want me to do." Those who gave the pledge go to my right hand, and remain in the School. Those who refused to promise would go to my left, and were to be sent back to their homes. They could not stay in the School without making the promise. I made it clear that this choice would be final, and the disobedient could never come back. Evidently they got my meaning.

The line began to move toward me. One made the promise, and went to my right. Another refused, and went to the left. And so the line kept dividing until we had about fifty on the right and nearly an equal number on the left. Then the stubborn ones were told that they had made their choice and were now out of School. I began to work with the ones who had promised to obey.

Now the sons of chiefs and evangelists and teachers who thought they would have some fun at the expense of the new missionary were on a spot. During the next few days my fellow missionaries were besieged by the boys and their parents and friends asking that they intercede with me, and reinstate the disobedient in the School. Mukelenge Kabemba (that was my name) simply could not do such a thing to people who were as important as they were. But I let the missionaries know that I had given my word, and I would rather leave the School than break a promise. As a result those who had stayed in realized that they were fortunate to have made a wise choice, so my problem of discipline was greatly simplified. Throughout my missionary life I had comparatively little trouble with discipline, as a result of this one painful experience which made my reputation.

The work of the School and sawmill went so well that on his return from furlough Mr. Stegall invited and urged me to stay with him in this work. While I recognized its importance I felt I should be engaged more directly in the evangelistic work, so I declined the kind invitation and asked the Mission Meeting for a new assignment.

Concurrently with the work at the Industrial School Mr. Stegall operated a steam sawmill nearly four miles away in the great forest, down by the Lulua River. The equipment included an American steam boiler and engine such as are common with portable sawmills. There was good sawing equipment, using 48 inch circular saws, with removable teeth. There was also some good woodworking machinery: a bandsaw, a planer, and a combination woodworking machine. I had been trained to use planing mill equipment, but not to saw logs. Mr. Stegall instructed me in that. I was to spend two or three days a week at the sawmill.

Mr. Stegall had left an excellent organization. There were about 100 men in the gangs, most of them employed in the forest. They cut trees, made roads, and dragged logs to the mill. Most of the trees in the forest were not desirable for our work, so the logs we wanted often came quite a distance. Only man power was available for this slavishly heavy work. Part of the forest gangs also served as mill hands whenever the mill itself was in operation.

The sawmill had a capable foreman. He was a tall, strong, handsome African, and he knew his job. One Sunday afternoon at Sunday School he came walking up the aisle with his wife, all dressed in white, looking quite distinguished. They were presenting their baby for baptism. I felt quite proud to have an assistant so good-looking and so capable. Imagine my extreme disappointment not long after, when I was told that this same man had been called before the Church Session and found guilty of selling spare parts of sawmill machinery to Bakuba blacksmiths. Of course the man had to be dismissed from his responsible position. That made the load of my own work much heavier.

The path to the sawmill lay through miles of primeval forest, thousands of great and beautiful trees and jungle plants. Heavy vines were swinging from the trees here and there. Riding down on a bicycle in the cool of the early morning was delightful. Monkeys played in the trees, birds sang, and altogether the tropical scene was a feast for the eyes. When I was tired with the day's work two men would tie a rope to the bicycle, and pull me up the long hill to the station.

When I worked at the mill Mignon sent me nice dinners to eat right on the job. I kept knife, fork and spoon, and a few dishes in the cupboard at the mill. The sentry was supposed to keep them clean. One day I was about to eat my dinner, and found a curly black hair in my fork. Table forks at that time were not common among the native people. The hair in the fork called for a little detective work. A fork was so much like an African comb that somebody had to try it in his hair.

But finding a hair in one's fork was not as bad as the experience of one of our missionaries who could not understand how his toothbrush stayed so wet. One day he got the answer when through a mirror he happened to see his houseboy brushing his teeth with employer's toothbrush!!

Twice at the sawmill we were scared by engine trouble. Once the belt of the governor which controls engine speed broke. As a result the engine out of control was driving the big saw at terrific speed, and the saw was shrieking furiously. Fortunately we got it stopped before serious damage was done. On another occasion a pulley broke. It was a wooden pulley in an idler arrangement which maintained the tension of the large, heavy belt which operated the saw. When the pulley broke and was thrown off, the shaft of the idler fell down on the belt. Each time the laced belt-joint passed under the shaft it made a terrible noise. The racket was fearful, and scores of heels showed as their owners ran for the tall timber. The engineer and I, both feeling responsible, ran for the throttle and reached it at the same time. So the machinery was stopped and nobody hurt.

One day I set myself a task. I had selected certain number of logs, and cutting them into lumber was to be the day's work. Everything was running nicely. My working position was between the big saw and log carriage on my left, and the heavy belt going perhaps a mile a minute on my right. Suddenly my eyes blacked out. I stood clinging to the operating lever until I could stand again. If I had fallen to the right or to the left I would almost certainly have been killed instantly. It was impossible to finish my task. So we closed for the day. Mounting my bicycle I was pulled home, though I could hardly keep my balance. I felt very sick. When I got home I looked for Mignon and could not find her, so I decided to go to our bedroom and lie down. She was already in her bed and said, "You have come to a hospital." I replied, "That is what I need," and went to bed for a week. Both of us were extremely ill with bilious malaria fever. We were too ill to look after our baby daughter. So our colleagues nursed us both and baby Alice, through a very hard week. I tried to give enough orders to the various foremen and teachers to keep the School and sawmill in operation. But it was hard going. My fever reached lO4 1/2 degrees.

Mr. McKinnon and Dr. Stixrud both had sawmill experience, and they helped me out by doing a lot of sawing while I was behind with my work.

Some readers will remember the epidemic of the Spanish influenza which visited many countries during World War I. After the worst had passed in Europe and America it also swept Africa. It was a fearful scourge, and brought death to many in Congo. We were told that before our steamer Lapsley left Kinshasa on a trip up river, people were dying in such numbers that some lay unburied in the streets. On the trip up river four members of the crew died, and many others were ill. So before the steamer reached Luebo the captain sent a messenger overland to find Dr. Stixrud to warn him. He at once secured the help of the government to quarantine the steamer. It was anchored in the middle of the river, and soldiers with rifles were stationed on both sides of the river to enforce the quarantine. This proved to be most necessary, for relatives of the crew tried to swim the river to get to them, and had to be forcibly restrained. The Bakete people near Luebo were called on to furnish some of their portable prefabricated houses, which could be carried in sections and set up quickly. These were erected on an island, and the sick from the steamer were hospitalized there until they recovered. Then after a safe interval, the uninfected members of the crew could return to their homes.

Then a new problem arose. It was the custom to unload the steamer cargo on the riverbank. Hundreds of volunteers from the village came to carry the cases up the hill, where they were paid for their work. The warnings about the flu which had accompanied the quarantine were so effective that no volunteers showed up to carry the loads. The students in the Mission schools had to be called out of school to serve as porters.

It was really remarkable that this quarantine was 100% effective. For the native people have always been quick to believe false rumors, and if the disease had spread from the Lapsley and brought death to many, the Mission would have been blamed.

Through the goodness of God it did not spread at that time. But a month later another steamer brought the flu up the river, and another wave of infection reached us overland coming from the east. It took strong hold of our population, and many foreigners and natives were very ill. We were thankful that at Luebo the death rate from flu was lower than elsewhere. Dr. Stixrud and the hospital staff worked day and night with the sick.

Reference has been made to baby Alice. She was born in the midst of the flu epidemic. Dr. Stixrud officiated but his wife was unable to assist because she was ill with the flu. I was an untrained nurse assisting the doctor. A native woman nurse helped to take care of mother and baby daughter until flu invaded her own home. Some of the missionary ladies helped when they could. The flu was reported to be deadly for mothers and young babies. We were indeed thankful to God that our little family was spared from infection, though most of the helpers around the house had flu at one time or another. However, the good Doctor was so busy with flu patients that he failed to give the usual attention to the baby's feeding. When he did check he found that little Alice was slowly starving. He at once arranged for change of feeding, and her life was saved.