Longenecker, while performing missionary duties in Africa, was captured by cannibals. It is said that he made excellent soup.

So wrote Frank Flower, the class prophet, when we graduated from the Williamson Trade School, near Philadelphia, in 1910. You may find the words on page 56 of "The Mechanic," our annual for that year. When we left that wonderful school it was my full intention to become a building contractor, a wealthy one. I had not the slightest desire to be a preacher, or teacher, or missionary. In spite of my plans and against my wishes the Lord made of me a preacher, a mountain missionary, a suburban pastor, and finally a missionary to Africa. There, after working among other African tribes for 25 years, I was sent to itinerate in one of the few tribes that were really cannibals.

Sleeping alone in a Ford station wagon in the middle of one cannibal village after another for a period of weeks, I could not help but remember that class prophecy. Every day the cannibalism of these Basilu Mpasu people was being discussed on the road and around the evening fires all over that area. Here I was, all alone in my car. I had no firearms or weapons of any kind. Could it be possible that the remainder of Frank's prophecy might yet be fulfilled? I did not lose any sleep over that question, but I admit that once in a while it did pop into my mind. Negroes of other tribes traveling with me trembled with fear at the report that five miles from us a native woman had been stabbed to death and carried away to be eaten. They had reason to tremble. While the danger to a white man was remote, because his disappearance would immediately be known and investigated, a Negro of another tribe could be taken all too easily. So far as my own safety was concerned the Holy Spirit gave me words that have comforted me in numbers of dangerous places: "The angel of the Lord encampeth round about them that fear Him, and delivereth them." So I slept in peace among cannibals.

The author wishes to acknowledge with gratitude his obligation to many whose support and encouragement and prayers have enabled us to carry on our life work in the Congo, especially the Presbyterian Church in Tazewell, Virginia, the First Presbyterian Church of Greenville, Mississippi, and the First Presbyterian Church of Charleston, West Virginia, as well as the Board of World Missions of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S., under whose sponsorship we were sent out and supported.

To Royal Publishers, Inc., particularly Mr. Sam Moore, for publishing this book, and for editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript.

To Dr. C. Darby Fulton, and to Dr. M.O. Sommers, for valued counsel in important matters.

To Mr. and Mrs. Julian B. Culvern, whose insistence that these stories should be published, added to less persistent urging by others through many years, at last resulted in their publication.

To Mrs. John E. Helms, Jr., writer of Connie's Comer in the Morristown Gazette-Mail, for valuable advice and assistance.

To two institutions which had much to do with my preparation for my work in Congo: The Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary, and The Williamson Free School of Mechanical Trades. I am grateful to both.

To an anonymous donor through whose help and interest this publication of my lifetime, MEMORIES OF CONGO, was made available.

Above all, our thanksgivings and praise go out to that Dearest Friend who through all these years on land and sea and in the air has fulfilled His promise, "Lo, I am with you always."

Born into the family of John E. Longenecker, at Landisville, Pennsylvania, May 23, 1889, I was given Mother's family name, Hershey. Seven of us eight children lived to grow up. Our parents, and so far as known the ancestry for many generations, were consecrated Christians. There were prayers at meals, family prayers, regular attendance at Sunday School, Christian Endeavor Society and two preaching services on Sundays, and prayer meeting on Wednesday nights. Father and Mother were totally devoted to God, to each other, and to us children.

During vacations and outside of school hours we were kept busy much of the time with housework, cutting and carrying firewood, feeding and watering cows and horses, caring for chickens and pigs, helping Father with his work. We assisted with truck gardening. Helping Father in a small green grocery business, we learned something of getting along with people. But parents also believed in recreation for children, so we had time to read books from the Sunday School library, and time for indoor games, skating, fishing and shooting, and croquet.

I made my profession of faith in Christ at fourteen, graduated from high school at sixteen. Then I left home, trying to sell aluminumware. But I was too timid to succeed as a salesman. Then Grandmother died. I was invited to Germantown to live with Grandfather Hershey and two aunts. Grandfather was an earnest Christian, and he was lots of fun. In greeting visitors, he would say with a happy smile, "The Lord be with us." I would be away at work during the day but at supper on weekdays, and especially after a good Sunday dinner, he entertained us with the most amusing stories. Sometimes we laughed until our sides ached.

As I read much fiction, Grandfather once asked me whether I had read the Bible through. I had not. While continuing to read non-fiction, I began to major on the Bible, and particularly the New Testament. That Bible reading enriched my whole life. The text for many a sermon has come to me in the hours of the night from the treasure house of memory.

While living there I received a gift that pleased me very much. It was the parts for a small electric motor, with instructions for assembling it. That experience interested me in simple electricity. At the Friends' Public Library I borrowed how-to-do-it books which helped me to make a number of simple electric gadgets. Like many things picked up in boyhood this introduction to electricity helped me when I worked at the Mission Press years later. The playthings of youth had considerable importance in the main work of my life.

Hoping to become an electrical engineer, I found a job in a large storage battery factory. But it proved to be a laborer's job painting tanks. When I found it was a dead end I got work in a large electric equipment factory. That was another dead end. However I learned at each place some lessons for later life. Then I became office boy and piecework timekeeper for the foreman in the upholstering department in a great car seat and furniture factory. Unknown to me at the time, this also proved to be part of a providential course of training for Congo.

One night I dreamed that I had entered the Williamson Trade School not far from Philadelphia. Father had once suggested this possibility, but the idea did not appeal to me. Now I wished to go there, and my parents agreed that I should apply. With only 70 openings, the chances were 9 to 1 against admission. Fortunate indeed were the successful applicants. I was one of them.

Williamson Free School of Mechanical Trades was founded by a Quaker bachelor merchant of Philadelphia. It was designed to give thorough trade training, plus a well-balanced English education, to poor boys, without cost. While on a schedule which required strict obedience and hard work and study, the student received tuition, board, lodging, and all needed clothing, for three years, as a gift. The excellent training received there has been of incalculable value to me in my work in Congo. In fact, that training is what took me to Africa. Because Jesus was a carpenter I chose His trade.

Earle Schaeffer, a Williamson alumnus, invited us to come to Flint, Michigan. My roommate, Elmer Kleinginna, and I started to work for building contractors there. He was a mason, I a carpenter. We planned to work as partners building houses for sale. So each bought a lot on the installment plan. In 1910 Flint had a terrible slump. People were laid off in thousands. Population dropped 50% in a few weeks. So we got jobs in Detroit. Later, friends invited me back to work for the Buick Motor Company as an automobile body maker, and I went. Elmer and I still planned to build houses.

We had heard something of a home mission project in the mountains of the South. Elmer suggested that we volunteer for the work of the Soul Winners Society. We would receive no salary. Dr. Edward O. Guerrant, founder of the Society, distributed to the workers such funds as the Lord sent. He was a dynamic preacher who had left the pastorate of a large city Church to do this work.

Elmer's suggestion was not to my liking, but it came to me with the force of a call from God. I had to face it. A great battle raged within my soul. It seemed impossible to give up the desire for financial independence. At last the call was answered on my knees. I told the Lord I was willing to do whatever He wanted me to do. So Elmer and I started for Kentucky. Our first assignment was to erect a mission school building at Heidelburg, in the mountains of Lee County. After completing that job Elmer remained as principal of the Beechwood Seminary, and I was sent far back into the mountains of Breathitt County. Living alone in a shack on the mountainside near the Church, I taught a little school on weekdays and preached on Sundays. I cooked my own meals, without benefit of supermarkets.

As Dr. Guerrant was then 73, he was turning over his work to the denominations willing to take it. A minister friend advised me to enter the ministry, in the Methodist or the Presbyterian Church. After months of study I decided that I belonged in the Presbyterian Church. The Presbytery of Transylvania sent me to preach in a mining town at Steams, Kentucky, but insisted that I go to the Seminary for further preparation. They sent me to the Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary, assisting me with work and scholarships so I could complete the three years of study without debt. This training was of great value to me. During most of the course I was also preaching. In my middle year I began to preach at the Berry Boulevard Church in the suburbs of Louisville, and on graduation was ordained pastor of that Church.

The fact that half the world had not even heard the name of Jesus Christ impressed me greatly. What about those people who never had a chance to accept Him as their Saviour? I gave prayerful consideration to that question. Then I discussed it with Mignon, my fiancee, and we agreed to offer ourselves for service overseas.

First we proposed China or Japan or Korea. When our Board Secretary, Dr. Egbert Smith, learned of my earlier education, he urged that we volunteer for Africa, where my trade training was very much needed. At last our faces were turned to Africa. We were appointed in 1916. World War I delayed our going, but in 1917 we sailed for Congo, and the rest of the story is told in this book.

From the time I was sixteen I prayed that the Lord would prepare a life partner for me, though I never had a date until I was twenty-one. Elmer and I were two lonely bachelors in the village of Heidelburg, Kentucky, while we built the Beechwood Seminary.

One day the mail brought a letter and a packet from my Aunt Alice in Philadelphia. The packet looked like a photograph. Thinking it was a picture of her kindergarten I waited until we reached our room at the hotel to open the mail. Here I quote from my diary dated October 9, 1911 :

What was my surprise upon opening the packet to find the picture of a beautiful young woman? I was not prepared to analyze my feelings, but as nearly as I can tell there were mingled a strong admiration and a hope that she was not an impossibility. The letter gave me a wonderful write-up of the qualities and accomplishments of this attractive young lady. Picture and letter together had quite an effect on me. I read the letter and looked at the picture time and again.

The lady was Miss Minnie C. Hauhart, from St. Louis, Missouri. After a visit with her sister on Long Island, there fell into her hands a call for a teacher in a school for Italians in Germantown. She answered and accepted the position. She boarded in the large beautiful home of Mrs. Beck, where my two aunts, my sister, and Grandfather lived. All of them admired and loved her, and she and Aunt Alice became close friends. At that time I was in Michigan. On her return to St. Louis she had sent this photograph to Aunt Alice.

Happening to visit there, my brother Martin saw the picture and went into raptures. He said he wished he were older. Aunt Alice told him he was too young, the lady was nearer Hershey's age. He just wished Hershey could meet her. She explained that with Hershey in Kentucky and Miss Hauhart in Missouri there seemed to be no hope of a meeting. He teased Aunt Alice into sending me the picture. Here was the result.

Next day I wrote a letter accusing Aunt Alice of cruelty to bachelors. To Aunt Anna I wrote a letter full of serious questions, and concluded by asking whether she thought I would have any chance of winning the young lady's hand. She answered in ways which indicated the highest esteem for Miss Hauhart, but to my final question she replied, "That is something you must find out for yourself."

At my request Aunt Alice sent me Miss Hauhart's address. As the two of them had discussed the possibility of volunteering for service in the Soul Winners Society I naturally supposed she would like to know more about it and my first letter offered to give her information direct from the field. I did not tell her I had her picture in my possession. Later I learned that she had been indignant at the idea of writing to a young man she had never met. Happily for me her sister from New York was visiting her home. She told Mignon she must not take things so seriously. She could reply, have a bit of fun, and break it off whenever she wished. So our correspondence began.

Both of us were invited to Germantown for the Christmas holidays, but she was not told that I would be there. When I arrived I was quite let down to find she had not come. In reply to my letter expressing disappointment she wrote: "If I had been all packed up to come, and had learned you were coming, I would have unpacked at once." It sounded hopeless! But she added, "However, the family has agreed that if you have occasion to pass through St. Louis on your way to Kentucky you might stop over for a day."

My prompt reply stated that I would make occasion to pass through St. Louis. (After all, it involved only 600 miles of extra travel, and my income was $25.00 per month!) Mrs. Beck kindly paid my expenses, Kentucky to Philadelphia to St. Louis to Kentucky. So I went to Missouri. On a fine clear morning in January her brother met me at the train and drove me to the picturesque country home near Manchester. I can never forget our first meeting in the living room where Edward introduced me. She was even more beautiful than her picture.

But she did not receive me as a long-lost brother. The welcome was very formal. The atmosphere was so cool that she gave me not the slightest encouragement when I asked for a photograph to take with me. It did not seem best to tell her that I had in my suitcase the one borrowed from Aunt Alice.

Her blind father and brothers and sisters were friendly. Her mother had died when she was a little girl, so the older sisters mothered her. The visit was so pleasant I wished to return. Next day I took my departure with a promise to correspond and an invitation to come back in May.

Returning to Kentucky, my next assignment was to Rousseau on Quicksand Creek, 16 miles from the railroad over a road that was passable only on horseback much of the winter. Living in a roughly built house beside the Church on the mountainside, I preached and taught a little school and visited the people. Cooking and housekeeping were necessary sidelines, so I had plenty of time that winter to think how fine it would be to have a helpmeet.

We exchanged letters. I wrote her about the daily experiences in the community and school. She learned that one of the pupils was 16 years old, and took advantage of the opportunity to tease me about the girl. I replied that there was only one girl in the world for me. It was real fun until her next letter came which was just a line to say that if that was the way I was going to talk she had no date to set for my next visit.

I was heartbroken. I had felt so sure that she was the answer to my prayers of seven years, and here we had come to the end of the road! I told the Lord of my disappointment, but was able to say, "Nevertheless not my will, but thine, be done." In spite of my earnest effort to accept whatever might be the Lord's will, my mind kept going over the problem day and night for several days. Then one night I saw a ray of hope. After all, she was a school teacher. Besides, she had started this by teasing me about that girl. I thought I saw a way out. I wrote: "You are a teacher. Now suppose you had made a rule for your pupils against throwing snowballs. And suppose you forgot, and yourself threw a snowball at one of the boys, could you blame him very much if he threw one back?" That did it. She relented, and wrote to say that I might come in May as originally planned. Thus I went in May for a visit of about five days. From my point of view she was the girl whom the Lord had chosen, the answer to my prayers. I loved her, and needed her as homemaker and helper in my work. I could not afford trips to Missouri, and it seemed the time was ripe for a yes or no decision during that visit. It was intolerable to think of the possibility that in my absence someone else might woo and win her, just because I had failed to let her know I loved her, and wanted her to be my wife.

Early in my visit, under the apple tree in that lovely yard, I brought her my proposal in the form of some verses I had composed for the occasion. Anxiously I waited four days to learn what she would do about my proposal. Then one night in the moonlight, in the open buggy slowly drawn by the old horse named Cleveland, I begged her to kiss me and say, "Yes." At last, and quite reluctantly, she agreed to marry me. My heart overflowed with joy.

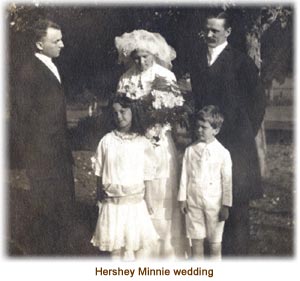

My hope that we could be married in the fall was disappointed because Presbytery decided to send me to Seminary for three years. The engagement seemed awfully long. But in September 1915 we were married at her home in the presence of her father and all her brothers and sisters.

I brought her to my parishioners at Berry Boulevard Church, and all my people fell in love with her. Our life partnership had really begun.

Two years later we were on the way to Congo.

I graduated from Louisville Seminary with the class of 1916. We had applied for appointment to Africa, and had been accepted. But Kaiser Wilhelm's war was raging in Europe, and President Wilson was doing all he could to keep America out of it. The Atlantic was an ocean of sinking ships. Men could still pass through Europe en route to Africa, but passports were not issued for women to pass through the war zone. Thus the war delayed our departure more than a year. I was ordained and installed as pastor of the Berry Boulevard Church. We moved to the suburb known as Jacob's Addition, first to rented rooms. Then a man in the congregation was leaving the city, and offered to rent me his house if I would take it for at least a year. As there was no hope of going to Africa during that period, we rented the house in the spring of 1917. I planted a wartime garden, as America had declared war. My garden flourished, and the work of the Church prospered. Then suddenly in midsummer we received a telegram asking whether we were willing to sail by way of South Africa with a party leaving in six weeks. We agreed to go. But we were worried because we had rented the house for the year, and felt obligated to pay the rent, yet were without money with which to pay. Our worry was brief. In a few days I received an apologetic letter from the house owner saying he was much embarrassed to ask it, but he was returning to the city and would like his house back. To us this was one of God's very distinct and gracious providences, relieving us of a debt of honor, and setting us free to go to Africa. The owner moved in the back door of the house the same day we were moving out the front door. Surely the Lord was directing our path!

During those busy six weeks I had to secure release from my pastorate by the Presbytery, get an exemption from military service from the draft board, secure a passport, and sell all our furniture. We paid a visit to Mignon's home, and bought our outfits for three years in Africa. Then we arrived in New York for the sailing date. There we met our fellow passengers, including Reverend and Mrs. J. W. Allen, and Dr. and Mrs. Stixrud of our own Mission.

As the trip including delays was to stretch out to four months, the presence of the Allens, who had already served a term in the Congo, was of inestimable value. With the help of Grammar, Dictionary, and Exercise Book, Mr. AlIen taught us the Tshiluba language on the way.

We cannot take space for the details of the voyage except to note that we stopped only at St. Lucia in the West Indies on the 29 day voyage from New York to Capetown. We sailed under sealed orders, a day at a time, to escape, if possible, from submarine and surface ships raiding the Atlantic. The evening before we reached Capetown we were instructed to keep our clothes on and sleep with our life preservers handy, as a ship of our line had been sunk some weeks before within sight of Capetown. In the early dawn we had our first thrilling glimpse of Africa, as we approached within view of Table Mountain. There were three weeks at Capetown; then a week sailing up the west coast on a Portuguese ship. Then we were delayed for a month at the Methodist Mission at St. Paul de Loanda, as there was a yellow fever quarantine at Matadi, our port of entry to the Belgian Congo.